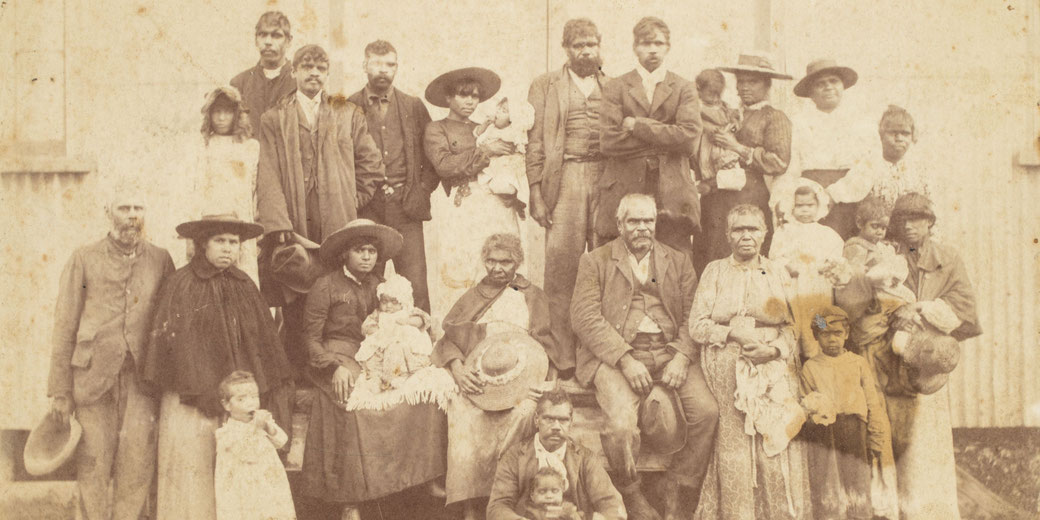

What were Aboriginal Reserves and Missions?

Aboriginal reserves, missions, and stations were an important part of Australian history.

They were established to help Indigenous people transition into European society, and to provide them with access to education and medical care.

Unfortunately, many of these institutions were plagued by racism and discrimination.

Aboriginal reserves

Aboriginal reserves were specific areas of land set aside by the Australian government for the habitation and protection of Indigenous Australians.

Established primarily during the 19th and 20th centuries, these reserves were part of a broader policy aimed at controlling and assimilating Aboriginal people into European society.

The first such reserve was established at Flinders Island in Tasmania in 1832, following the Black War, with the intention of isolating Aboriginal people from the colonial settlers.

Over time, the reserve system expanded across the Australian continent, with the establishment of the Aborigines Protection Board (APB) in various states, such as New South Wales in 1883.

These boards were responsible for the administration of the reserves and had significant control over the lives of the Indigenous inhabitants.

The reserves were often located on marginal land, with poor living conditions, limited access to resources, and restricted freedom of movement for the Aboriginal residents.

Indigenous people were generally not allowed to leave reserves without permission, and they were often required to live by strict rules.

For example, they might be banned from drinking alcohol or speaking their own language.

Aboriginal missions

Aboriginal missions were religious institutions established primarily by Christian missionaries in Australia, starting from the early 19th century.

These missions aimed to convert Indigenous Australians to Christianity and, similar to the government-run reserves, sought to assimilate Aboriginal people into European ways of life.

They were established by religious groups such as the Catholic Church or the Anglican Church.

The first mission was established at Wellington Valley in New South Wales in 1832 by the Church Missionary Society.

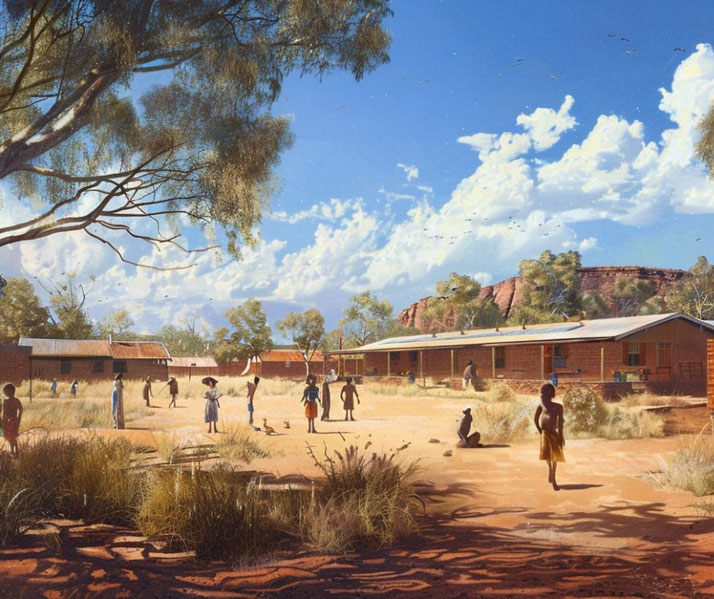

Missionaries often settled in remote areas, where they would build churches, schools, and other facilities to serve the local Aboriginal community.

Life on the missions was strictly regulated, with Indigenous residents typically required to attend religious services, adopt Western dress codes, and speak English.

Children were often separated from their families to be educated in mission schools, a practice that contributed to the loss of Indigenous languages and cultural practices.

The missions played a complex role in the lives of Aboriginal people. While they provided some education and healthcare services that were otherwise unavailable, they also facilitated the government's policies of control and assimilation.

Aboriginal stations

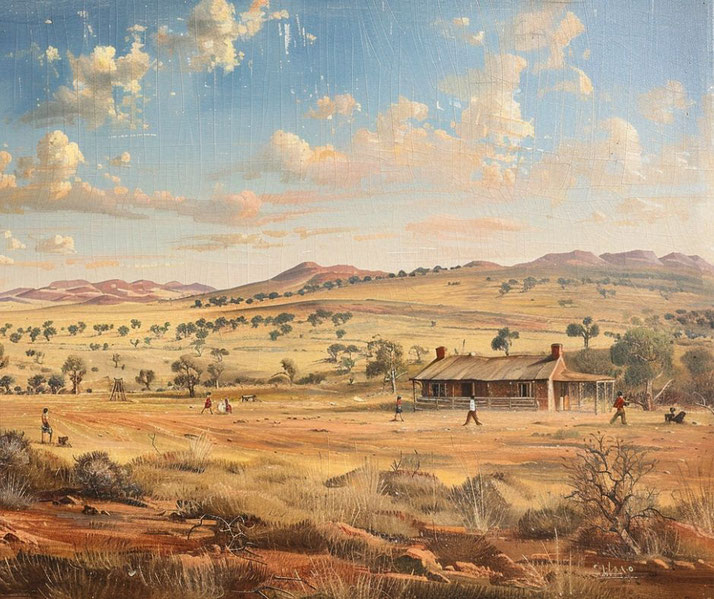

Aboriginal stations were large tracts of land that were set aside for Indigenous people to live on.

Aboriginal stations were often run by the government or private landholders and were used for pastoral or agricultural work by Indigenous people, sometimes under conditions very similar to forced labour.

Stations were often very isolated, and life on them was often very hard. First Nations people living on stations often had to fend for themselves, with little help from the outside world.

Aborigines Protection Act of 1909

The Aborigines Protection Act of 1909 was a turning point in the history of Aboriginal reserves, missions, and stations.

The Act gave the APB more power to control the lives of Indigenous people living on these institutions.

Under the Act, the APB could force First Nations people to live on reserves and missions, and they could make rules about what they could and couldn't do.

The Aborigines Protection Act was a controversial piece of legislation, and it was eventually repealed in 1969.

Conditions

Many Indigenous people were reluctant to abandon their traditional way of life to live on reserves or missions.

They found the conditions on these institutions to be very difficult, and they experienced a great deal of racism and discrimination from the Europeans who ran them.

The conditions on many of these reserves, missions, and stations were poor. There was often a lack of food and medical care.

Many First Nations people died from diseases such as smallpox and influenza.

Racism was also a problem on many of these institutions. Indigenous Australians were often treated as second-class citizens.

They were not allowed to marry Europeans, and their children were taken away from them and sent to white schools.

Despite the challenges, First Nations people were considered to 'benefit' from living on reserves, missions, and stations.

They were given a European education and medical care that they would not have otherwise had access to.

Impacts

The Aboriginal reserve system finally ended in 1969 with the repeal of the Aborigines Protection Act.

However, the damage had already been done. The Aboriginal reserve system was a key part of the government's assimilation policy.

This policy aimed to 'integrate' Indigenous people into white society.

The assimilation policy had a devastating effect on First Nations culture and language.

Many Aboriginal people lost their connection to their traditional way of life and their land.

They were also subjected to racism and discrimination.

The legacy of the Aboriginal reserve system is still felt today. Many Indigenous people feel that they were a form of cultural oppression.

There are many First Nations people who live in poverty and lack basic services such as education and health care.

There is also a great deal of racism and discrimination against Indigenous people in Australian society.

Further reading

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2024.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.