The 7 worst kings and queens of England

History tends to glorify kings and queens, but some managed to mishandle their royal duties with astonishing incompetence. From disastrous decisions to serious failures in diplomacy and leadership, a few English monarchs earned their place in the history books for all the wrong reasons.

1. King John (1199-1216)

During the early thirteenth century, John inherited a kingdom already burdened by the historical impact of his father, Henry II, and the legendary reputation of his brother, Richard the Lionheart.

Almost immediately, John demonstrated a lack of skill in managing England’s vast Angevin holdings in France.

Within five years, he lost Normandy, Anjou, and parts of Aquitaine to Philip II of France.

The military failures resulted partly from his strategic missteps, but also from his well-known distrust of key barons, which weakened the feudal bonds crucial to medieval warfare.

Domestically, John’s rule became a byword for tyranny. He collected very high taxes, imposed harsh fines on his nobles and clashed with the Church.

His dispute with Pope Innocent III led to England’s excommunication in 1209 and placed the country under papal interdict.

To fund his military campaigns, John demanded scutage from his barons on at least eleven separate occasions during his reign, far exceeding his predecessors and heightening baronial discontent.

By 1215, the barons had revolted, forcing John to sign the Magna Carta, which he quickly repudiated.

When civil war broke out, some barons even invited Prince Louis of France to claim the English throne.

John’s death in 1216 halted further collapse, though much of southeast England remained under the control of Louis of France.

The monarchy survived largely due to the actions of William Marshal, who rallied support for John’s young heir.

His disastrous reign permanently damaged the prestige of the monarchy.

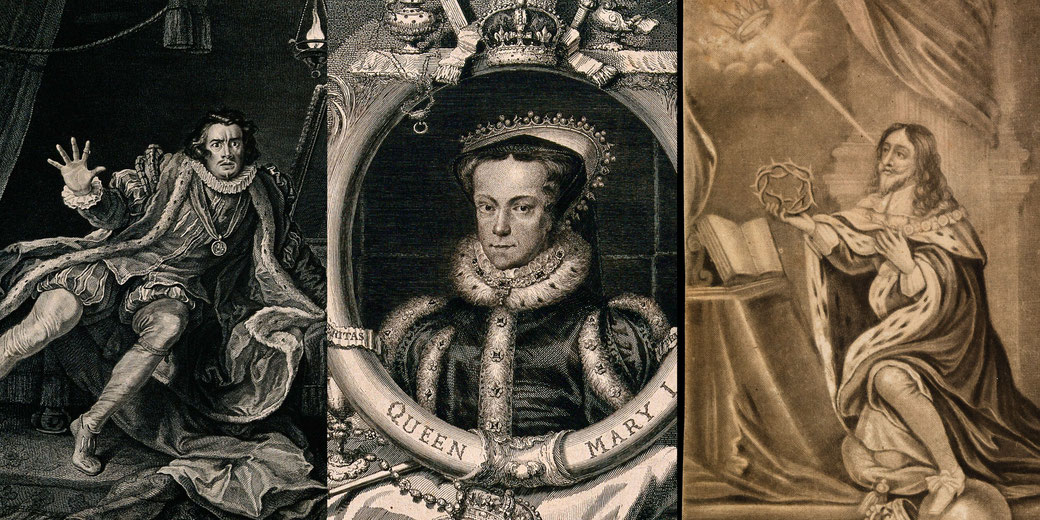

2. Richard III (1483-1485)

Before ascending the throne, Richard of Gloucester built a career as a loyal commander during the Wars of the Roses.

However, after the unexpected death of his brother Edward IV in 1483, Richard seized power through actions many saw as betrayals.

He declared his nephews illegitimate, imprisoned them in the Tower of London, and may have been involved in their murder, though no definitive proof has ever surfaced.

Known as the Princes in the Tower, their disappearance caused a scandal that haunted Richard's reputation.

As king, Richard attempted to strengthen royal authority by promoting legal reforms and offering protection to the poor, but those efforts were overshadowed by the circumstances of his rise.

People continued to question his right to rule, and his support base weakened quickly, with defections of key nobles such as the Duke of Norfolk and the Earl of Northumberland.

In 1485, Henry Tudor challenged him at the Battle of Bosworth Field. During the fight, Richard charged into enemy lines and was killed, ending the Plantagenet dynasty.

His death culminated in the downfall of a monarch whose pursuit of power undermined the stability of the kingdom.

3. Henry VI (1422-1461, 1470-1471)

When he ascended to the throne as an infant, following his father Henry V's death, the young king inherited an English kingdom at the height of its power in France.

However, he lacked the temperament and ability to manage a kingdom that had been fractured by war and noble rivalries.

During his early years, regents governed in his name, but when he came of age, Henry showed little interest in leadership.

He suffered from long periods of mental illness and indecision, which left a dangerous leadership void.

Under Henry’s rule, England lost nearly all its French possessions, triggering widespread discontent.

His inability to control the feuding nobles contributed directly to the outbreak of the Wars of the Roses.

Margaret of Anjou, his ambitious queen, took an active role in politics, but her leadership divided the court further.

After being deposed by Edward IV in 1461, Henry briefly regained the throne in 1470, only to be captured and die in the Tower of London in 1471 under suspicious circumstances that many believed to be murder.

His reign brought ruin to England’s foreign ambitions and fuelled decades of civil war.

4. Edward II (1307-1327)

At the start of his reign, Edward II alienated powerful nobles because he favoured a small circle of personal companions.

His close relationship with Piers Gaveston, whom he repeatedly promoted and defended, created resentment among England’s barons.

Gaveston’s execution in 1312 by a group of angry lords failed to resolve tensions, and Edward’s subsequent reliance on the Despenser family only deepened the conflict.

His failure to build consensus with his nobility weakened royal authority.

Military defeats compounded Edward’s failures. In 1314, at the Battle of Bannockburn, his army suffered a crushing loss against the Scots under Robert the Bruce.

This defeat significantly undermined England’s position in the north. By the late 1320s, his estranged queen, Isabella of France, led a rebellion with her lover, Roger Mortimer.

Edward was captured, forced to abdicate in favour of his son, and later died in Berkeley Castle, with widespread belief at the time pointing to murder, though some later accounts questioned the exact circumstances of his death.

His reign showed the dangers of showing favouritism and of weak military leadership.

5. Mary I (1553-1558)

After years of political uncertainty, Mary Tudor assumed the throne in 1553 determined to restore Roman Catholicism in England.

Her reign soon became known for harsh persecution of Protestants. Under her authority, nearly 300 people were burned at the stake for heresy, including prominent religious figures such as Thomas Cranmer, Hugh Latimer, and Nicholas Ridley.

These executions, widely publicised, earned her the nickname “Bloody Mary” and created long-lasting religious bitterness.

Her unpopular marriage to Philip II of Spain, a devout Catholic and foreign prince, stirred fears that Spain would dominate English affairs.

Parliament resisted efforts to grant Philip power, and the union failed to produce an heir.

Mary’s attempts to restore papal authority, combined with the loss of Calais to France in 1558, further eroded confidence in her rule.

By the time of her death, England had gone through economic hardship and outbreaks of religious violence that fuelled political instability. These problems weakened support for Catholic restoration.

6. James II (1685-1688)

By the time James II became king, England had already endured a civil war followed by a period as a republic before restoring the monarchy.

His open Catholicism clashed with the mostly Protestant political establishment.

He insisted on appointing Catholics to military and political office, in direct violation of the Test Acts.

In 1687, he issued the Declaration of Indulgence, which suspended laws against Catholics and dissenters, angering both Parliament and the Anglican Church.

When his wife gave birth to a Catholic son in 1688, fears of a Catholic dynasty prompted a group of nobles to invite William of Orange to invade.

James fled the country, and Parliament declared that he had abdicated. The Glorious Revolution that followed ended his reign without widespread bloodshed but permanently altered the balance of power in England.

James's disregard for parliamentary authority and Protestant concerns made his rule one of the most unstable in English history.

7. Charles I (1625-1649)

As the son of James I, Charles inherited a strong belief in divine right monarchy.

From the beginning of his reign, he clashed with Parliament over taxation, royal prerogative, and religious policy.

In 1629, he dissolved Parliament and ruled without it for eleven years in a period known as the Personal Rule.

During this time, he imposed controversial taxes and attempted to enforce religious uniformity through Anglican reforms, which alienated both Puritans and Scottish Presbyterians.

His attempts to force the Anglican prayer book on Scotland in 1637 sparked a rebellion that spread into England and forced him to recall Parliament.

However, the Long Parliament resisted his authority.

In November 1641, Parliament passed the Grand Remonstrance, a document listing over 200 grievances against Charles’s rule.

This widened the rift between king and Parliament and tensions escalated into the English Civil War in 1642.

After years of conflict, Charles was captured, tried, and executed for treason in 1649.

His death was the first time an English monarch had been publicly executed by his own subjects, and it ushered in a republican experiment under Oliver Cromwell.

Charles’s rigid views and refusal to compromise drove the country into war and temporarily ended the monarchy itself.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.