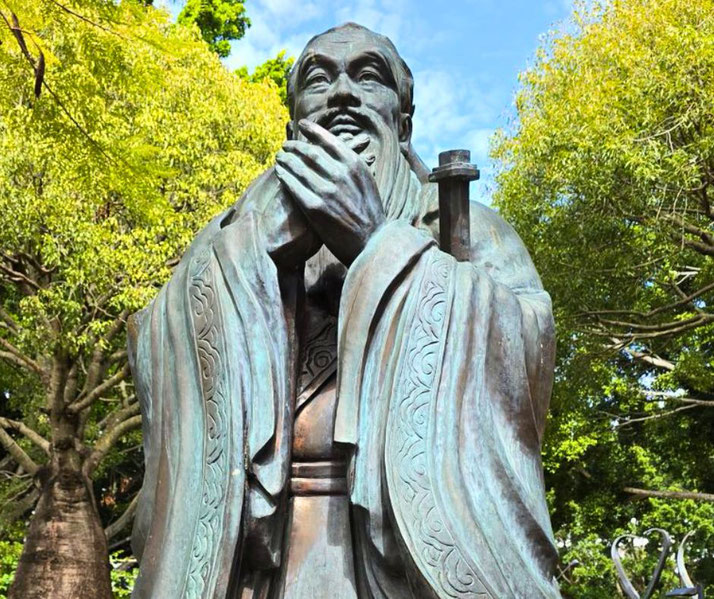

Who was the real Confucius, the greatest philosopher in Chinese history?

Few people have left as much as a lasting impact on Asian culture as Confucius. His ideas about balance, moral behaviour, and respect for families spread across China and, over time, the world as well.

What we know about his life

While we know him as Confucius, he was born with the name Kong Qiu in 551 BC in the state of Lu, near today’s Qufu in Shandong Province.

This was during an era known as the ‘Spring and Autumn period’ of the Zhou Dynasty, where wars were being fought across much of the country.

His father, Kong He, had served in the military, but died when Confucius was only three years old, which left the family struggling financially.

The young Confucius loved to learn, and He learned poetry and history, plus the six traditional skills: rituals, music, archery, chariot driving, writing, and mathematics.

He was also curious about why people lived different lives depending on their levels of wealth.

Once he had become an adult, Confucius married and had three children. In order to support them, he reportedly worked in a number of government jobs where he was in charge of the horse stables and responsible for recording grain supplies.

How he became a famous teacher

At about 30 years old, he had a career change and became a teacher, which was usually only permitted for people from the noble families.

However, he decided that his school would accept all students, no matter what their social background was.

He was more interested in their abilities, not their family name nor their wealth.

He taught his students a wide range of subjects, including history, poetry, government, but also focused on explaining how to have proper behaviour.

In particular, he promoted the concepts of "ren" (often called "kindness" or "humaneness"), "li" (often called "rites" or "ritual"), and

"xiao" (filial piety), or respect and duty towards parents and ancestors.

When combined, it conveyed the overall idea that respect was the most important part of human relationships, especially those who had power over others: such as ruler and subject, older and younger, and even friends.

He described the "junzi" (the ideal person) as someone with strong moral character, as shown in their kindness, fairness, and a sense of responsibility towards others.

In fact, Confucius believed everyone was subject to these ideas, including the government.

He even said that it was the rulers who should set a moral example to inspire the common people to act rightly.

He spent part of his life on journeys through various states where he tried to encourage leaders to follow his ideas, but he was met with mixed reactions.

In his late 60s, after years of political disappointment and wandering, he returned to his home state of Lu.

He concentrated once more on his teaching and, according to tradition, worked on editing old Chinese texts.

Much of what we know about Confucius comes from The Analects, which is a collection of his sayings and discussions with students, which was put together after his death.

The famous disciples of Confucius

His repution during his life drew many people to Confucius and his teaching. As a result, he gained a devoted group of followers, some of which became quite prominent themselves and continuing his teachings after he passed away.

Yan Hui was his favourite student and was responsible for preserving what Confucius had taught for later generations to follow. Sadly, he died quite young.

Another student was known as Zilu, who was famous for his bravery. His talks with Confucius make up much of the Analects.

Zengzi was a third key student who people believe helped write the "Great Learning" and the "Doctrine of the Mean", two of the four main Confucian books.

Later thinkers such as Mencius and Xunzi were not directly taught by Confucius but were responsible for studying his ideas and expanding on them. They are often called the second and third sages of Confucianism.

Each of these students and followers played an important role in helping to turn Confucius' ideas into an influential philosophical movement that could be shared easily with others.

Does Confucianism have any 'holy books'?

The teachings of Confucius have been passed down through several important texts, mainly the Four Books and Five Classics.

The Four Books are the Analects, the Mencius, the Great Learning, and the Doctrine of the Mean.

The Analects is by far the most important of these. It is our most reliable record of Confucius' views on many subjects.

The Mencius contains the teachings of Mencius, while The Great Learning and the Doctrine of the Mean help explain Confucian moral ideas according to Zengzi and his grandson Zisi.

The Five Classics are the Book of Changes (I Ching), the Book of Documents (Shu Ching), the Book of Odes (Shi Ching), the Book of Rites (Li Ji), and the Spring and Autumn Annals.

All of these works are believed to have been edited or compiled by Confucius at some point and cover a range of subjects, including history, poetry, divination, and religious rituals.

However, it is important to note that there is academic debate about who really wrote these texts and when they first appeared.

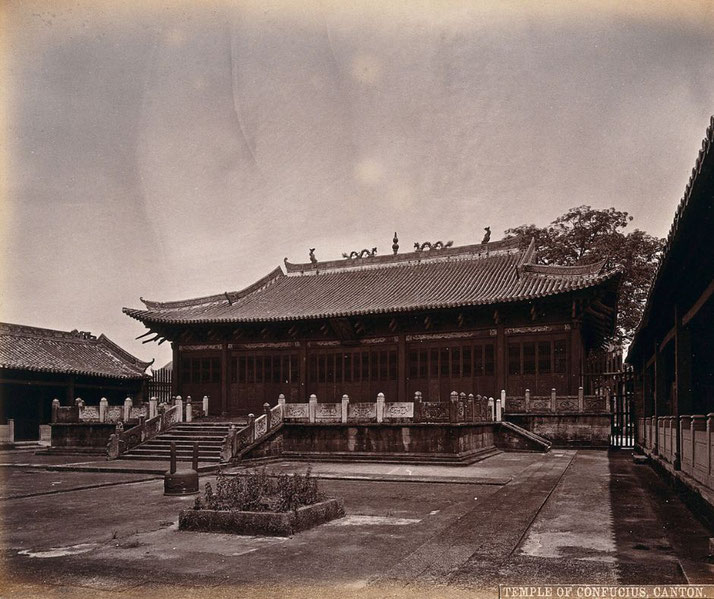

Confucius' profound impact on Chinese society

At first, during the later Zhou Dynasty (which ended in 256 BC), Confucian ideas were only one of several competing philosophies.

Then, during the Qin Dynasty (221–206 BC), Confucianism was actually banned, with its books publicly burned and many of its scholars buried alive. This was because Emperor Shi Huangdi thought that it was a threat to his imperial rule.

It wasn't until the Han Dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) that Confucianism finally became the state ideology when Emperor Wu made it the official philosophy of his empire, and set up schools funded by the state to teach Confucian texts.

Thanks to this, Confucian principles soon became key parts of government and social attitudes, especially regarding respect for parents and socially acceptable behaviours.

The junzi, or ideal gentleman, became the ideal role model for all government officials.

It also led to the introduction of the civil service examination system in the Sui Dynasty (581–618 AD), which would last all the way until the end of the Qing Dynasty in 1912.

These exams tested a students’ knowledge of Confucian texts and offered a way into government jobs, which aimed to reward merit rather than birth.

In times of political chaos, like the late Han Dynasty, Confucian teachings became a moral guide which was used to judge the actions of rulers, while the common people turned to Confucian ethics for stability.

How Confucian philosophy has changed over time

At different times in Chinese history, the popularity of Confucianism declined and it had to be reinvented by new generals of followers to regain its importance.

One of these revivals was known as Neo-Confucianism, which began during the Tang Dynasty (618–907 AD) before reaching the height of its influence under the Song Dynasty (960–1279 AD).

It sparked a renewed interest in classical Confucian thought as scholars aimed tried to combat the spread of the newer Buddhist and Daoist ideas.

These Neo-Confucian thinkers even borrowed elements of these new beliefs systems to provide new teachings about the world and the universe that traditional Confucianism had not discussed directly.

One of the earliest leaders of this movement was Zhou Dunyi, who introduced many of these new metaphysical ideas in his work, “Explanation of the Diagram of the Supreme Ultimate”.

In it, he described concepts like the interaction of Yin and Yang and the Five Elements.

Meanwhile, the brothers Cheng Hao and Cheng Yi focused on ethical self-improvement and inner moral awareness, which reinterpreted Mencius’s view of human goodness in accordance with Neo-Confucian thought.

Perhaps the most important Neo-Confucians thinker was Zhu Xi. He set out the Four Books as the core of Confucian teaching and his notes on them became the standard interpretation for centuries.

Thanks to its success in China, Neo-Confucianism began spreading to neighbouring regions, including Korea, Japan, Vietnam and, eventually, to the rest of East Asia.

How did Confucian thought conflict with other beliefs?

Confucianism was only one of a number of competing ideas that appeared during the period of time known as the ‘Hundred Schools of Thought’.

As these schools competed to be adopted by those in power, they often clashed with each other.

One of the other popular movements was known as Legalism, which was originally linked with Han Feizi.

While Confucius taught moral virtue for government, Legalists supported stricter laws and punishments, as they thought people were naturally self-interested and needed rules.

Legalism saw its greatest influence during the Qin Dynasty (221–206 BC), which used it to justify a very strict set of rules.

This led to the suppression of other beleif systems, including Confucianism itself.

Centuries later, Daoism, which had been founded by Laozi and developed further by Zhuangzi, asked people to live in harmony with the Dao, a universal principle.

When it appeared in China, Daoists criticised Confucius’s focus on rituals and social hierarchies.

They instead encouraged a more natural and spontaneous life. However, at times, Daoism and Confucianism could work together in the minds of the Chinese people.

Some people used Daoism for their spiritual life and relied upon Confucianism for their ethical and social roles.

Often forgotten today, Mozi created a system called Mohism, which supported “universal love.”

He said that people should care for all people, not just their families, which was intended to be a direct challenge to Confucian teachings.

Also, Mohists taught pacifism and championed the use of plain logical in arguments.

Finally, Buddhism came to China after the Han Dynasty period, and with it came ideas like karma, nirvana and the monastic life, which differed substantially from Confucian views.

It quickly became popular with the Chinese people, but, over time, was merged into the Neo-Confucian school of thought, which reduced the tensions between the two groups.

Further reading

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.