What happened when the Ancient Romans encountered Ancient China?

At the height of their power, the Roman Empire and the Han Dynasty ruled as the two largest and most powerful civilisations in the known world.

Roman authority stretched across Europe, North Africa, and the Near East, while Han China controlled large territories that extended from the Korean Peninsula to Central Asia.

Because they lay thousands of kilometres apart, they did not maintain regular diplomatic contact, but they did gain knowledge of each other’s existence through long-distance trade and scattered reports from foreign merchants.

East verses west: Same or different?

Roman and Chinese civilisations grew according to distinct principles. Roman society rested on the ideas of legal rights that structured civic life and endorsed military expansion alongside public service.

Emperors such as Augustus projected an image of stability by maintaining traditional titles and preserving elements of republican government.

Citizens pursued status through military success complemented by growing wealth and active civic participation, and Roman engineers built a network of roads, aqueducts, and large buildings to serve their expanding empire.

Meanwhile, Han China developed around different foundations. Imperial authority drew its right to rule from the Mandate of Heaven, and Confucian ideals strengthened social order through a system of hierarchy that encouraged obedience and promoted learning.

The central administration managed taxation, infrastructure, and military command, while a growing class of educated officials advised the emperor and implemented state policies.

Under rulers such as Emperor Wu of Han, growth into Central Asia and the use of Confucian practices shaped the imperial structure.

Although dynastic power sometimes changed hands through force, the ideal of stable and moral rule stayed central to Chinese political thought.

Religion and philosophy also followed different patterns, as Romans worshipped a pantheon of gods adapted from Greek and eastern traditions, and many citizens participated in mystery cults that promised personal salvation.

Meanwhile, Chinese belief systems combined ancestor worship, Taoist principles, and early ideas about the universe, which explained the balance of natural forces and the proper behaviour of individuals within society.

Cultural achievements in each civilisation are a good indication of these values, from Roman epic poetry and law codes to Chinese historical writing and astronomical studies.

The Five Relationships of Confucianism helped to define the ethical structure of society, and texts such as the Analects reinforced moral conduct and social duty.

How were these empires connected?

A large network of roads and caravan paths, known today as the Silk Road, enabled the movement of goods, ideas, and people across Asia.

No single trader travelled the entire route. Instead, goods passed through a chain of middle traders, each operating within their own territory and profiting from the growing demand for luxury items.

Sogdian, Kushan, and Parthian merchants became key figures in this system, as they handled both goods and information from distant regions.

Cities such as Samarkand, Merv, and Dunhuang were important hubs for rest, resupply, and exchange.

It is from this that Roman merchants purchased Chinese silk in large quantities.

Wealthy Romans wore silk garments as status symbols, and tailors in eastern cities sold imported bolts to elite clients across the empire.

Chinese silk workers guarded the secrets of sericulture, and no foreign trader learned how to reproduce the process.

In return, Chinese markets received Roman glassware, coral, amber, and finely worked metal goods.

Artisans from Alexandria and Antioch, in particular, created glass vessels that found their way through Central Asia to China’s western provinces.

Some scholars suggest that Parthian merchants may have discouraged direct contact between Rome and China in order to maintain their position as intermediaries.

However, any real knowledge of each other’s existence developed gradually.

Roman authors referred to a mysterious eastern land called ‘Sinae,’ and Chinese records described a distant empire known as ‘Daqin,’ which scholars now identify as the Roman world.

Neither side sent official envoys for centuries, but rumours and fragments of second-hand information passed between them through countless commercial interactions.

Evidence of long-distance trade before contact

Long before any formal diplomatic missions took place, material goods from each civilisation reached the other.

Silk garments became so popular in Rome that members of the Senate proposed laws to limit their use.

Some writers complained that silk weakened Roman masculinity and drained wealth from the empire, yet public demand continued.

Nevertheless, the popularity of Chinese silk in Roman markets remained constant across generations, and merchants continued to transport it through the eastern provinces.

Roman artefacts have been discovered in regions far beyond the empire’s borders.

For example, coins attributed to Roman emperors, including Tiberius and possibly Marcus Aurelius, have turned up in southern China and Vietnam, though the exact dating and route of arrival remain not clear, as some may have arrived long after they first left Rome.

Central Asian tombs yielded glass vessels, bronze ornaments, and fine textiles that originated in the Roman Near East.

At sites such as Noin-Ula in Mongolia and Óc Eo in Vietnam, archaeologists uncovered Roman medallions, beads, and jewellery that clearly showed transcontinental movement.

Chinese documents also describe embassies from kingdoms situated between the Han court and Daqin.

As a result, China and Rome often relied on second-hand information and reports filtered through regional powers.

In fact, Parthians sometimes manipulated such reports to discourage direct contact between the empires and preserve their control of the Silk Road.

When the Romans finally met the Chinese

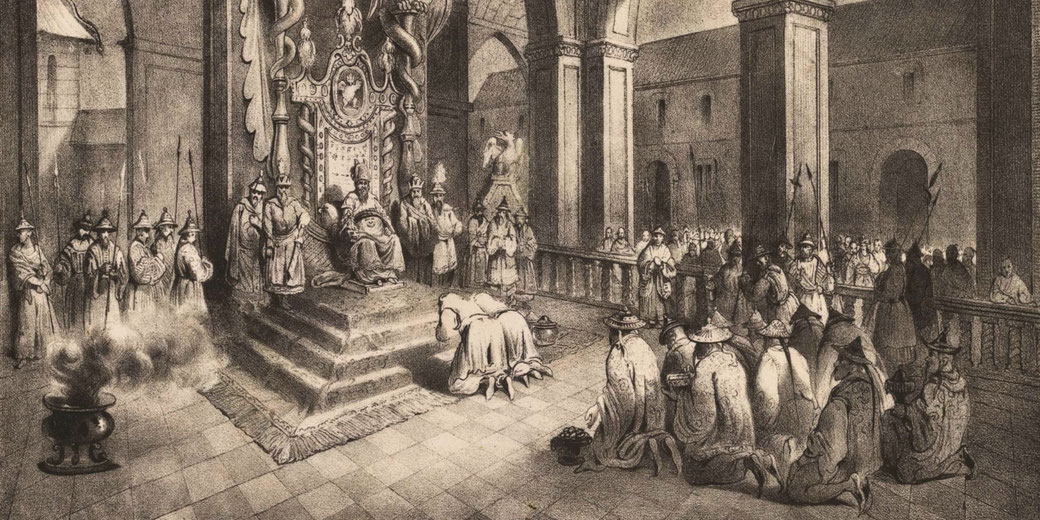

The first recorded diplomatic contact between the Roman Empire and Han China occurred in 166 AD.

According to the Hou Hanshu, a group claiming to represent the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus arrived at the Chinese court, though no Roman source confirms the mission and most scholars interpret it as a private trading delegation rather than an official embassy.

The Chinese called him ‘Andun,’ and the delegation entered Han territory through the port of Rinan, in present-day Vietnam, before travelling to Luoyang to present gifts.

Rinan belonged to the southern commanderies of the Han Empire and was an entry point for sea trade with Southeast Asia and India.

Han officials described the visit as a formal act of tribute, in keeping with Chinese traditions of international diplomacy.

Most scholars believe the delegates were eastern merchants from Alexandria or Syria, who identified themselves as Romans to gain prestige and improve their trading position.

The Hou Hanshu noted that the visitors brought ivory, rhinoceros horn, and tortoiseshell as gifts, which may indicate their origin in maritime trade networks.

Further contact occurred in the early third century. According to the Weilüe, Roman merchants travelled by sea from the Persian Gulf to India and then continued on to Chinese ports with the help of monsoon winds.

The voyage was dangerous, and shipwrecks, illness, and piracy claimed many lives, but successful traders reached new markets and returned with great profits.

Chinese officials recorded their arrival as part of the growing international activity along southern trade routes.

What did the two cultures think of each other?

Roman views of China were vague but generally positive, as geographers such as Ptolemy described ‘Sinae’ as a land of wealth and refined culture.

Some Roman authors associated silk with mystery and decadence, but few detailed descriptions of Chinese society survived.

The term ‘Seres’ also appeared in Latin texts to describe peoples from the far east, though its exact application remains uncertain.

In comparison, the Hou Hanshu described Daqin as a wealthy and orderly civilisation with large cities, moral rulers, and fair laws.

Writers praised Roman technology and architecture, including their road systems and stone buildings.

One account stated that the people of Daqin appointed rulers based on merit and rejected corruption, a claim that may have originated from merchants exaggerating their homeland’s qualities or Chinese officials projecting their own values onto foreign reports.

Chinese documents also referred to Roman goods as "luminous gems" and "fire pearls," likely descriptions of glassware and jewellery.

Chinese writers believed that Daqin had equal status to the Middle Kingdom, but they still described it within the structure of a tribute system.

Roman merchants and envoys appeared as guests offering gifts rather than representatives of a sovereign power.

This view showed Chinese ideas about world order rather than a detailed understanding of Roman politics or diplomacy.

But all may not be as it seems...

Remember, that much of the contact between Rome and China occurred through intermediaries who shaped the narrative for their own benefit.

Parthian and Kushan rulers had little incentive to allow direct interaction between the two great empires, so, by managing information and restricting movement, they preserved their position as essential middlemen.

Their ability to profit from east-west commerce relied on keeping Rome and China at a distance.

Some historians now argue that no official Roman embassy ever reached the Han court.

The supposed mission under Marcus Aurelius may have involved merchants pretending to act on behalf of the emperor.

Without any Roman documentation to confirm the journey and with the Chinese interpretation shaped by their diplomatic customs, it becomes difficult to determine the true nature of the visit.

Scholars such as Rafe de Crespigny and Yu Ying-shih have noted the absence of corresponding Roman sources such as Cassius Dio or the Historia Augusta.

Direct contact between the Roman and Chinese empires stayed rare, and both sides relied heavily on limited and often inaccurate reports.

Despite the lack of consistent diplomacy, the exchange of goods, stories, and imagined ideas of the other shaped how each civilisation understood the world beyond its borders.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.