What was the German army's strategy of 'blitzkrieg' in WWII and how did it work?

The German strategy of blitzkrieg, which translated as “lightning war,” focused on rapid movement supported by close coordination, so that attacks achieved surprise, and overran enemy defences quickly.

This approach changed warfare in the early years of the Second World War and allowed the Wehrmacht to defeat opponents quickly.

German planners developed it as an answer to the slow-moving trench warfare of the previous conflict that used large amounts of resources.

What was 'blitzkrieg'?

German military leaders, who had been frustrated by the long stalemates of the First World War, spent the 1920s and 1930s refining a new approach to warfare that rejected static lines and attrition.

In particular, General Hans von Seeckt, who led the German Army Command during the early years of the Weimar Republic, encouraged reforms that prioritised smaller units that were mobile and that received thorough training, so they could act rapidly and decisively.

His influence helped form the future development of German doctrine on how to conduct operations, even as the Treaty of Versailles restricted the German military's size and equipment.

Later theorists, especially General Heinz Guderian, focused on the role of armoured vehicles in breaking through enemy lines.

He argued that tanks should lead the main assault and drive deep into enemy-held territory rather than merely support infantry in narrow sectors.

His writings in the 1937 book Achtung – Panzer! outlined a system of warfare that combined mechanisation with extensive radio communication and that allowed leadership at lower command levels that could adapt quickly.

Guderian later helped put these ideas into practice during the Polish campaign of 1939, although the concept was not yet fully developed at that stage.

The word blitzkrieg itself did not appear in formal German military manuals, but journalists and Allied observers used it to describe the speed and impact of Germany’s early war victories.

Within the German army, officers sometimes used the term Bewegungskrieg, meaning “war of movement,” though this had existed as a general military concept since the First World War and was not always synonymous with blitzkrieg.

Regardless, German doctrine aimed to identify weak points in the enemy line, concentrate forces there, and then push through rapidly before defenders could react or reorganise.

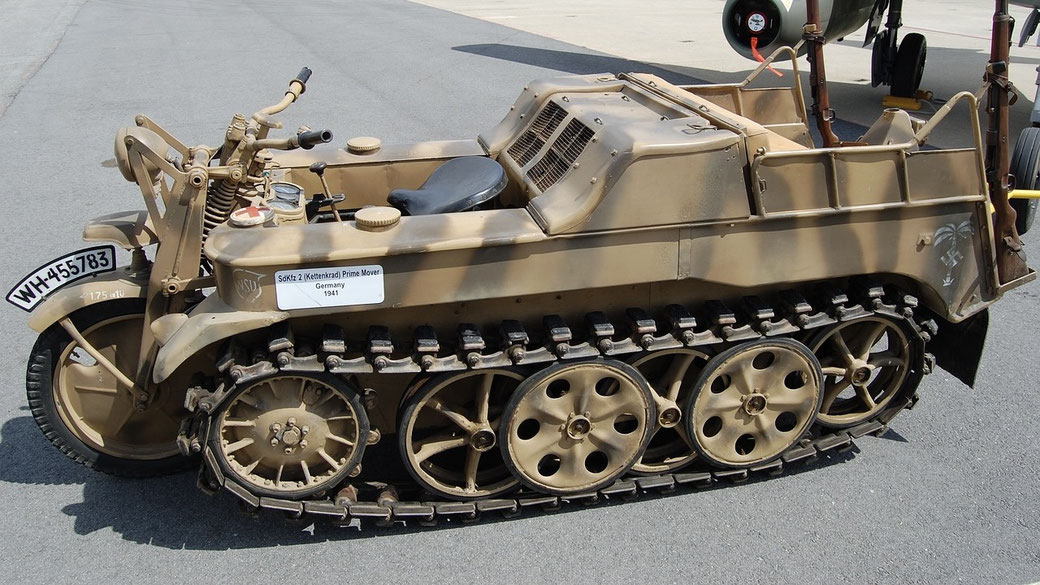

In practice, this required tanks, motorised infantry, and artillery to work in close coordination with aircraft.

German commanders used Schwerpunkt, which was the concept of focusing maximum force at a single point of attack, in order to breach the front and then send fast-moving columns to attack enemy communication lines, railways, and supply centres.

By cutting off reinforcements and surrounding isolated pockets of resistance, German forces could compel surrender without engaging in prolonged fighting.

This principle was shown at the Battle of Sedan, where German armoured units and dive bombers forced a rapid collapse of French defensive positions and enabled the crossing of the Meuse River.

As a result, the dive bombers, particularly the Junkers Ju 87 Stuka, played a key role in attacks that softened defensive positions and spread panic ahead of the advancing tanks.

The aircraft's mounted sirens, known as "Jericho Trumpets," created a terrifying noise during dives that added a psychological effect to the attacks.

However, these sirens were removed from later models due to aerodynamic drag and reduced battlefield effectiveness.

The Luftwaffe also struck behind the front, targeting airfields and roads to prevent the enemy from responding effectively.

As Panzer divisions advanced through the breach, motorised infantry followed to secure the flanks, deal with bypassed defenders, and secure captured ground.

How did blitzkrieg work?

Blitzkrieg relied on close coordination between ground and air forces, which required new communication systems, especially the widespread use of radio transmitters in vehicles.

This allowed tank commanders and infantry officers to adapt quickly when battlefield conditions changed, receive real-time updates, and exploit breakthroughs before the enemy could react.

It also enabled the central command to retain control over fast-moving operations across wide fronts.

German tactics depended on creating confusion and stopping the enemy from forming a stable line of defence.

When the Wehrmacht launched an assault, it selected a narrow corridor as the point of penetration, massed its armoured units there, and used overwhelming firepower to break through.

Once inside enemy territory, mechanised forces fanned out to disrupt command centres and capture strategic infrastructure.

The rapid encirclement of Soviet forces at Minsk in 1941 demonstrated the effectiveness of this approach.

In addition, commanders encouraged initiative at lower levels, which allowed junior officers to adjust their plans without waiting for higher approval.

When commanders gave authority to junior officers, German units could maintain momentum, change direction when necessary, and prevent defenders from stabilising the front.

Infantry divisions followed along secured paths where they mopped up resistance and held captured areas, and fresh mobile units continued the push forward.

The method also depended on encirclement of enemy formations rather than attempts to destroy every unit encountered.

German forces did not attempt to destroy every enemy unit they encountered.

Instead, they bypassed strongpoints, enveloped entire formations, and forced mass surrenders through isolation and psychological shock. In the best cases, this resulted in the collapse of entire armies within weeks of fighting, often before the bulk of reserves could be called up.

Blitzkrieg worked best when Germany held air superiority and could protect its mobile forces from aerial attack.

It also required secure supply lines, good weather, and terrain suitable for fast movement.

The strategy’s dependence on coordinated movement and rapid supply arrangements made it vulnerable when faced with harsh conditions.

Seasonal mud, or Rasputitsa, and the Russian winter later exposed these weaknesses.

If any of these elements failed, the entire strategy became vulnerable to disruption, particularly as it lacked the reserves and supply capacity required for prolonged engagements.

How it was used in Poland and France

The German invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939 demonstrated the core features of blitzkrieg, though on a smaller scale than later operations.

Over one million German soldiers attacked from three directions, while the Luftwaffe bombed rail lines, bridges, and airfields to prevent Polish reinforcements from coordinating an effective defence.

Panzer divisions punched through the Polish border defences, advanced rapidly towards Warsaw, and encircled several Polish armies in the process.

By the end of the campaign, Polish forces had suffered over 70,000 dead, 130,000 wounded, and nearly 700,000 taken prisoner, while thousands of civilians died in bombing raids and ground combat.

German casualties numbered approximately 16,000 dead and 30,000 wounded.

Poland’s army, which still relied heavily on cavalry and outdated equipment, could not match the speed or flexibility of the Wehrmacht.

Although some units fought determinedly and slowed the German advance in certain areas, they lacked the mobility and communication tools necessary to respond to the pace of the attack.

The entry of the Soviet Union from the east on 17 September further undermined Polish efforts, and by the end of the month, most major resistance had collapsed.

Then, in May 1940, Germany launched Fall Gelb, the offensive against France and the Low Countries, which caught the Allies by surprise.

German forces first attacked Belgium and the Netherlands, which drew British and French troops forward into central Belgium.

Meanwhile, the main German thrust moved through the Ardennes Forest, which French planners had believed impassable for tanks.

The attack began on 10 May and gained momentum within days.

Once the Germans crossed the Meuse River near Sedan on 13 May, their Panzer divisions advanced quickly toward the English Channel.

Within ten days, they had reached the coast, which trapped the British Expeditionary Force and large French formations in northern France.

Although the Allies managed to evacuate over 300,000 troops from Dunkirk, they lost nearly all their heavy equipment, and the French army suffered crippling losses in manpower and morale.

Paris fell on 14 June, and France signed an armistice on 22 June in the same railway carriage that Germany had used to sign its surrender in 1918, a symbolic gesture ordered by Hitler.

German success in France depended on rapid manoeuvre that used deliberate deception to conceal intentions and that exploited terrain carefully.

Their bypassing of the Maginot Line, exploitation of the lightly defended Ardennes, and rapid push to the Channel disrupted Allied planning and made organised counterattacks nearly impossible.

The campaign also highlighted the effectiveness of combined arms warfare, particularly the coordination between mobile ground units and aerial bombardment.

Its failure in Russia

In contrast, Operation Barbarossa, which was the German invasion of the Soviet Union launched on 22 June 1941, began with the largest application of blitzkrieg tactics in the entire war.

Three army groups advanced on different targets: Leningrad in the north, Moscow in the centre, and Kiev in the south.

In the opening weeks, the Wehrmacht inflicted devastating losses on the Red Army, and encircled hundreds of thousands of troops in pockets around Białystok, Smolensk, and Kiev.

By the end of 1941, German forces had taken over three million Soviet prisoners, the majority of whom later died in captivity due to starvation, exposure, and neglect.

However, as German forces advanced deeper into Soviet territory, they encountered several problems that undermined the effectiveness of blitzkrieg.

The great distances, poor roads, and deliberate Soviet destruction of rail infrastructure stretched German supply lines and made it difficult to deliver fuel, ammunition, and reinforcements to the front.

Supply systems designed for short, rapid campaigns could not support operations on such a scale.

Soviet commanders, after initial shock and disorganisation, began to regroup and improve their defences.

Stalin moved entire factories east of the Urals, well out of German reach, and called up massive numbers of conscripts.

The Red Army took early losses and began to conduct organised retreats that traded space for time and allowed Soviet industry to rebuild and prepare counteroffensives.

Marshal Georgy Zhukov played a central role in reorganising Soviet defences and leading successful counterattacks.

German leaders, especially Hitler, failed to agree on a single objective. Army Group Centre, which had advanced closest to Moscow, was redirected southward in August, allowing Soviet defenders to reinforce the capital.

When the offensive resumed in October, poor weather, inadequate winter clothing, and exhausted units slowed the advance.

By December, Soviet troops launched a successful counterattack outside Moscow, which pushed German forces back from the city during the Battle of Moscow.

Blitzkrieg failed in the Soviet Union because it depended on short campaigns and concentrated assaults, but the Red Army’s depth, manpower, and industry allowed it to absorb early defeats and continue fighting.

Once the German army became bogged down in a war of attrition, it could not replace its losses quickly enough or adapt to the prolonged demands of the Eastern Front.

German forces also lacked a formal written doctrine for blitzkrieg, which contributed to its uneven application and limited adaptability.

Allied forces later studied the principles of blitzkrieg and used elements of it in their own plans, especially in 1944 during the Normandy campaign, where air superiority and combined arms operations played a critical role in breaking through German defences.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.