How bad was hyperinflation in Germany in the 1920s?

Hyperinflation in Germany during the early 1920s was one of the most destructive economic events of modern times. In 1923, the value of the mark collapsed so sharply that banknotes lost their worth within hours.

Across the country, people who had once lived in relative comfort found themselves ruined by inflation that left wages worthless.

The same inflation eroded pensions and destroyed personal assets.

What is hyperinflation?

Economists commonly define ‘hyperinflation’ as a situation in which prices rise by more than fifty per cent within a single month.

Unlike normal inflation, which central banks can often manage with policy measures, hyperinflation can cause panic and lead to a complete breakdown in the value of money.

Currency loses its role as a store of value or a medium of exchange, and people begin to seek alternatives that will keep their value.

In economies hit by this kind of inflation, banknotes typically became worthless because they could not keep up with prices that were rising.

Wage earners suffered severely, since even frequent pay rises could not keep up with hourly price changes.

As the currency lost public trust, consumers often turned to barter or used more stable foreign currencies to buy food, fuel or other necessities.

Hyperinflation did not usually result from a real shortage of goods because it typically began when governments printed too much money.

Once people had realised that their savings were shrinking each day, they often spent money quickly or hoarded goods, which made the crisis worse, so by late 1923 prices were doubling approximately every four days.

What were the causes of Germany’s hyperinflation?

Germany entered the First World War in 1914 without having raised enough tax to cover military spending, so the imperial government issued war bonds and increased the money supply by printing, rather than cutting spending or raising revenue.

When the war ended in defeat in November 1918, the German economy was already unstable and inflation had begun, so the newly formed Weimar Republic struggled to recover financially while trying to honour the Treaty of Versailles.

The treaty had set reparations at 132 billion gold marks, a figure that remained theoretical and later changed under international agreements.

As the government did not have sufficient gold or foreign currency reserves, it met domestic obligations and reparation payments by continuing to print paper marks, which caused inflation to rise steadily in the early 1920s and become much worse after 1922.

In January 1923, French and Belgian forces occupied the Ruhr Valley after Germany defaulted on reparation payments in coal and timber.

The Ruhr proved vital to economic recovery as the country’s industrial heartland.

The Weimar government called for passive resistance and encouraged workers to strike. The government promised to pay wages, but production remained idle.

To fund these payments and maintain state services, the Reichsbank had printed ever larger amounts of currency, which had sped up the fall of the mark’s value, so by mid-1923 inflation had run out of control.

Banknotes appeared in values that presses could hardly keep up with, which even included a 100 billion mark note, the highest value the Reichsbank officially issued.

In some cities and industries, people received wages twice a day and often spent the money immediately because it would be worth less by the afternoon.

Reports at the time included stories such as customers who said that the price of a cup of coffee had doubled before they finished it.

The dramatic impact of hyperinflation

The collapse of the currency created economic conditions that affected every level of society, but the middle class suffered particularly.

Many people who had built up savings before the war had seen them disappear in months.

Many retirees and war widows had no way of keeping up with prices that doubled every few days, and salaried professionals who depended on fixed incomes had no way either.

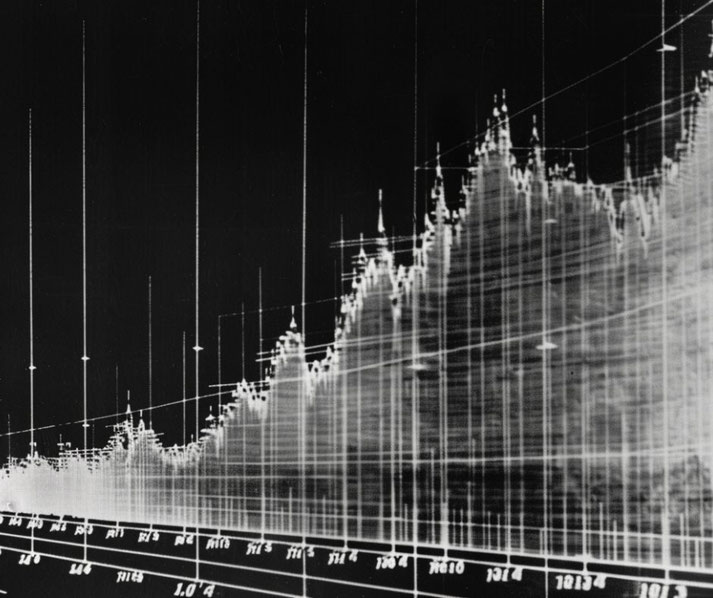

During the peak of the crisis in November 1923, one US dollar was approximately equal to 4.2 trillion paper marks, while a loaf of bread that had cost 250 marks in January that year rose to 200 billion marks by October.

Banknotes became so worthless that people used them as fuel, wallpaper or even toys for children.

Entire families searched for ways to get foreign currency or stable goods they could trade.

Businesses could not operate under normal conditions. Since prices changed by the hour, many abandoned printed price lists and turned to barter or foreign currency.

Restaurants stopped printing prices and shopkeepers wrote amounts on boards that had to be updated constantly.

In Berlin, women carried wages in baskets or wheelbarrows and hurried to markets before their money lost its value.

Those who owned land or factories or who held foreign assets retained some degree of financial security, and people who could access gold or hard currency avoided complete ruin.

For most Germans, however, inflation effectively destroyed any hope of stability and disrupted daily life.

Many lost faith in democracy and supported extremist groups that promised order.

How did the government try to fix the problem?

In the final months of 1923, political leaders recognised that urgent action was needed to stop the crisis.

Under Chancellor Gustav Stresemann, the government ended passive resistance in the Ruhr and ordered a halt to the printing of additional money.

Those steps proved politically unpopular, but they initiated a turning point in the struggle against inflation.

Stresemann served only 100 days as Chancellor and later became Foreign Minister and helped to negotiate the Dawes Plan and improve Germany's international position through the Locarno Treaties.

To stabilise the currency, the government introduced a new unit called the Rentenmark in November 1923, which did not become legal tender at first, but gradually won public confidence because the government followed strict monetary policy and because industrial and agricultural mortgages backed it.

The exchange rate set one Rentenmark equal to one trillion old paper marks. One Rentenmark had roughly the value of one US dollar, which allowed prices to become more stable.

The Reichsbank, which was led by Reich Currency Commissioner Hjalmar Schacht, took control of monetary policy.

New currency issuance had been strictly limited and short-term foreign loans had helped to support the recovery.

Those steps had been difficult and had helped to bring back trust in the monetary system and had allowed normal trade and banking activity to resume.

In 1924, the Dawes Plan was negotiated with international partners that included the United States, and was formally accepted in August 1924.

The plan changed the schedule for reparation payments and allowed Germany to get financial support, which led to economic growth returning slowly as industrial production restarted and the banking sector improved.

The introduction of the Reichsmark as a permanent currency in 1924 gradually replaced the Rentenmark as legal tender and finished the recovery from hyperinflation.

The aftermath and consequences of this period

Although the currency stabilised and industry recovered, many Germans never fully regained the financial position they had before 1923 because the economic collapse had wiped out years of savings and weakened trust in the Weimar Republic’s ability to govern.

People who had suffered during the crisis carried anger and resentment into the following decade.

Many middle-class families who had once supported liberal institutions moved away from a system that had failed to protect them.

The harm that hyperinflation caused stayed fresh in public memory and this fear of renewed inflation often influenced voting behaviour and affected government policy in the years that followed.

During the Great Depression, many Germans who remembered the chaos of 1923 rejected mainstream parties and supported radical alternatives.

Hitler and the Nazi Party used the memory of 1923 in their propaganda, blaming democratic leaders and promoting authoritarian solutions.

Historians and economists often use the 1923 German hyperinflation as a warning about the dangers of unchecked money printing.

The crisis showed that economic instability could quickly turn into social and political unrest.

Sadly, for the Weimar Republic, the experience proved a significant factor in the weakening of democratic rule in the years before Hitler’s rise.

Economic historians such as Adam Fergusson, who in his 1975 work When Money Dies studied this period, treated it as a warning about poor handling of public finances and widespread public despair.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.