Why did the ancient Egyptians build obelisks?

Ancient Egyptian obelisks are one of the most distinctive monuments of antiquity, and they have consistently drawn attention for their height and shape, as well as for the strange messages cut into their stone.

Egyptians called them tekhenu, which is often thought to mean “to pierce” the sky, and each example was a single block with a pyramid-shaped tip, known as the pyramidion.

Examples that survive range from under 10 metres to more than 30 metres in height.

But why did the Egyptians build them?

The mystical reason for their construction

Obelisks expressed a direct link between people and the gods, since Egyptian religion placed the sun at the centre of cosmic order.

The shape may have meant to represent a sunbeam cast into stone, and the tip mirrored the sacred Benben of Heliopolis, the original mound from which creation began in Egyptian belief.

At Heliopolis, priests linked the tip, which could be coated in metal (mentioned below) to shine in the sunlight, to the god Atum-Ra and described obelisks as monuments that shone to renewed the sun’s daily victory over darkness.

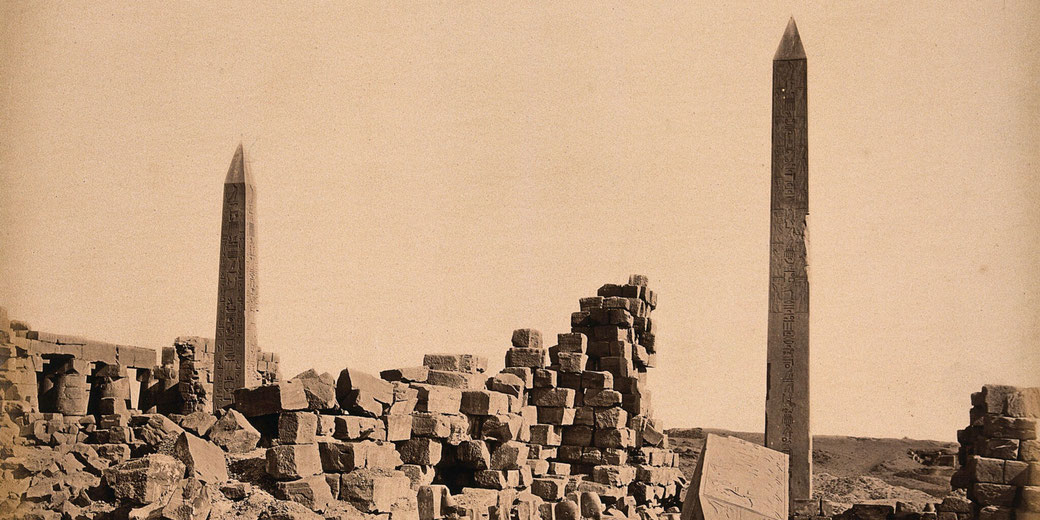

Obelisks were often erected in pairs at major temple gateways.

Priests treated the pyramidion as a focus for sunlight, and they often specifically covered it in electrum so that dawn light flashed across the surface.

Artisans sometimes used gold leaf on the apex for the same effect on clear mornings.

Inscriptions on the shafts named the pharaoh who commissioned them, honoured the sun god under titles such as Ra and Amun-Ra, and set out prayers for cosmic stability known as ma’at.

Scribes also recorded the king’s Horus name and prenomen in cartouches, along with titles such as “beloved of Amun-Ra,” and listed offerings the kings had provided to sustain order.

Temple architects planned positions for the obelisks that worked with the sun’s path through the sky along with ritual calendars, so an obelisk could catch first light on festival mornings.

The pair at Karnak framed processional routes during ceremonies such as Opet and the Beautiful Festival of the Valley, and the obelisk at Heliopolis set a visual marker inside Egypt’s oldest centre of sun worship.

The incredible way they were made

Obelisk projects began at the granite quarries of Aswan, where hard dolerite pounders left pitted marks that are still visible today at the Unfinished Obelisk.

Quarry gangs cut channels around a planned outline, undercut the bedrock, and freed the block without splitting it.

They then smoothed faces with quartz sand as an abrasive and checked for natural flaws.

Any hidden crack ended months of work, so inspections and test cuts became part of routine practice.

The Unfinished Obelisk at Aswan measured roughly 42 metres with an estimated mass of about 1,090 tonnes (≈1,200 short tons), and it was only stopped when a bedrock fault was discovered underneath it.

Transport to the final site relied on the use of sledges, ramps, and boats along the Nile.

Crews would drag the stone across prepared tracks that workers had wet with water to reduce friction, a method shown on Middle Kingdom tomb scenes such as the haul of Djehutihotep’s colossal statue.

Boat builders then loaded the block onto wide barges for the long river journey during the Inundation season, when high water made it easy to navigate between Aswan and temple ports at Memphis and Thebes as well as Lower Egyptian sites.

Once at the final destination, raising the monument required a controlled drop into a prepared socket.

Engineers built earth or sand ramps, used levers to move the base over the pit, and let the sand that supported it run out until the obelisk stood upright.

Hatshepsut’s inscription says the project, from the quarrying order to completion, took seven months.

The most famous Egyptian obelisks

The obelisk of Senusret I at Heliopolis dates to the early 12th Dynasty (Year 30 of Senusret I) and stands a little over 20 metres high, which makes it one of the oldest examples that survive.

Its Middle Kingdom inscriptions preserve early formulas and provide a reference point for later New Kingdom texts.

Hatshepsut’s obelisk at Karnak that was mentioned earlier rises to about 29.6 metres and was commissioned for Amun.

A second Hatshepsut obelisk at Karnak later broke, and its fragments still lie on site.

An earlier Thutmose I obelisk at Karnak survived at about 21.7 metres and showed the New Kingdom preference for paired shafts at pylons.

The Lateran Obelisk began under Thutmose III and IV for Karnak and now measures just over 32 metres.

The record shows joint authorship on its sides, and the original Egyptian base inscriptions confirm its Theban origin even though the shaft later travelled to Rome.

It is the tallest ancient Egyptian obelisk that still stands. It was taken from Heliopolis to Rome under Caligula, and has a shaft that is uninscribed in hieroglyphs, and later Latin inscriptions appear on its base.

Luxor Temple preserves one Ramesses II obelisk at its pylon, and its partner now stands in Paris.

The Luxor shaft that survives still carries scenes that match the pylon reliefs, so viewers can read a single royal message across the architecture and the single block of stone.

Why are Egyptian obelisks located around the world?

Roman emperors removed several obelisks from Egypt and installed them as centrepieces in imperial cities, since the monuments carried solar and royal meanings that suited public spaces.

Augustus, Caligula, and later rulers ordered shipments to Rome, where obelisks stood in circuses and forums as gnomons for large sundials.

Today, Rome has more ancient Egyptian obelisks than any other city, including more than remain in Egypt, and Augustus used one at the Campus Martius.

Movement of such stones advertised imperial reach and wealth, and it also showed command of expert labour.

Nineteenth-century collectors and political also leaders acquired obelisks through gifts and diplomatic deals as a result of Egyptology and from modern governments' interests.

Muhammad Ali Pasha presented one Luxor obelisk to France in the 1830s, and engineers raised it in the Place de la Concorde in 1836.

Britain raised “Cleopatra’s Needle” on the Thames Embankment in 1878 after a difficult voyage, and New York installed its twin in Central Park in 1881.

It wasn't really built by Cleopatra, htough, as Victorian audiences misapplied the nickname even though Thutmose III originally commissioned the shafts and Ramesses II later added his own inscriptions.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.