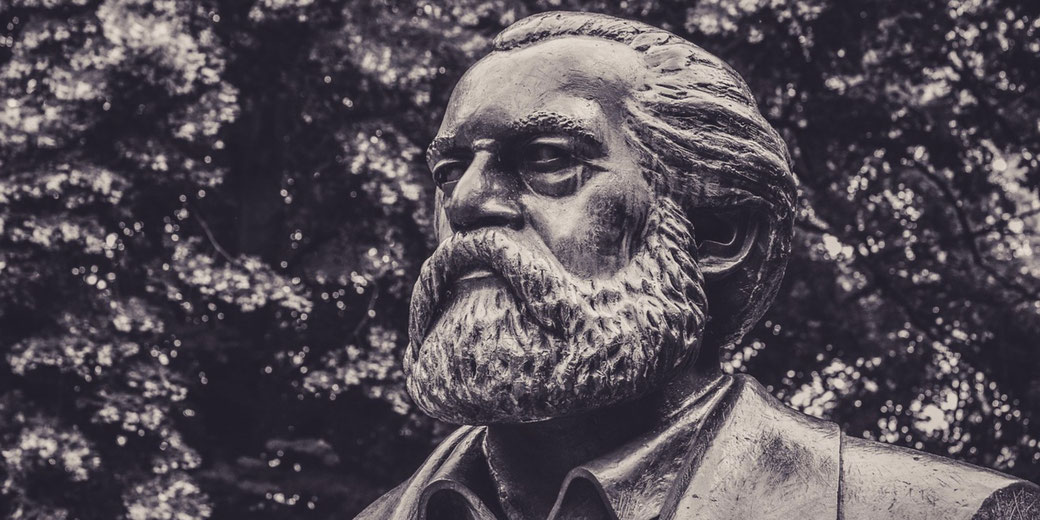

Who was Karl Marx, the man who created communism?

Karl Marx became one of the most influential thinkers in modern history, largely through the force of his ideas rather than through political leadership or military conquest.

His theories influenced revolutions, helped define ideologies, and changed the way people understood class and economic power.

Born on 5 May 1818 in Trier, Germany, Marx developed a worldview that challenged the foundations of Western society.

Although communist ideas had existed earlier, Marx developed the most influential form of modern communist theory.

Marx's early life, family, and education

Karl Marx entered the world in a politically tense region of the Rhineland at the time, where his father, Heinrich Marx, practised law.

To maintain his legal career under restrictive Prussian laws that barred Jews from many professions, Heinrich converted to Lutheranism in 1816.

As a result, Karl grew up in a Protestant household, though without strong religious instruction.

The family lived in relative comfort, and Karl enjoyed access to an excellent education and a wide range of classical and Enlightenment literature.

His high school teacher, Johann Hugo Wyttenbach, introduced him to key Enlightenment thinkers.

At the Friedrich Wilhelm Gymnasium, where he completed his secondary schooling, he developed an early interest in philosophy and history.

After graduation, he enrolled at the University of Bonn, although his troublesome behaviour and involvement in student life led his father to transfer him to the more rigorous University of Berlin.

There, he studied Hegelian philosophy, historical theory and law. Often, he had spent long hours in the university library, during which he had read across multiple disciplines.

Although he later criticised Hegel, Marx retained the dialectical method at the core of his intellectual framework.

He earned a doctorate from the University of Jena in 1841 for a thesis titled "The Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature," a doctorate which he received without studying there in residence.

Conservative authorities in Prussia, however, had little tolerance for radical thinkers at that time.

How Karl Marx's views developed over time

After completing his studies, Marx turned to journalism. At the Rheinische Zeitung, he published articles that criticised the Prussian government, denounced censorship, and supported reforms to ease the burdens placed on the working poor.

Eventually, his writing drew government attention. By 1843, the government had shut the paper down. As a result, Marx left Germany and moved to Paris.

There, he had encountered other revolutionary thinkers who expanded his understanding of social inequality.

He read French socialist works, including those by Saint-Simon, Fourier, and Proudhon, and discussed political ideas with other exiled German intellectuals.

Gradually, he shifted from liberalism to a more radical critique of society and he began to argue that the problems of capitalism did not come from poor governemnets or corruption.

Instead, they arose from how the economic system itself operated. In Marx’s view, the ownership of the means of production by a small class ensured exploitation and inequality.

In 1845, the French government expelled him under pressure from Prussian officials.

By the mid-1840s, Marx had constructed the main features of historical materialism in which he believed that the economic base of a society, which determined its laws and political institutions, also influenced cultural practices.

He argued that history progressed in stages based on the dominant mode of production.

These stages have often been described as primitive communism, slavery, feudalism, capitalism, and, eventually, socialism.

While Marx himself did not always present this model systematically, it became central to later Marxist theory.

Each system contained internal contradictions that would eventually produce class conflict and revolution.

According to Marx, capitalism had developed the productive forces to an unprecedented level, but its dependence on wage labour created a sharp divide between capitalists and workers.

His collaboration with Friedrich Engels

In 1844, Marx met Friedrich Engels in Paris. Engels was the son of a wealthy industrialist who had observed working-class conditions in Manchester and reached similar conclusions about capitalism’s impact.

Their meeting led to a lifelong partnership in which they shared ideas, drafted political programs and exchanged thousands of letters.

Engels had recently published "The Condition of the Working Class in England," which deeply impressed Marx.

Importantly, Engels provided Marx with regular financial support. Without it, Marx would not have been able to dedicate his life to writing and research.

Together, they composed The Communist Manifesto in late 1847 for the Communist League, a small revolutionary group of German workers.

Published in London on 21 February 1848, the pamphlet called for the overthrow of the bourgeoisie, paired with the abolition of private property and the establishment of a classless society.

The manifesto’s tone was direct and urgent, and it declared that history was the story of class struggle.

It ended with a call for workers of the world to unite. As revolutions swept across Europe in 1848, the text quickly circulated among radicals.

Its influence reached far outside what Marx or Engels had expected at the time.

How Marx saw the world

Marx believed that capitalism operated on exploitation. He claimed that, in many cases, workers created far more value than they received in wages.

The gap between a worker’s labour and the capitalist’s profit, which Marx labelled “surplus value,” formed what Marx called the basis of capitalist accumulation.

According to him, this extraction not only denied workers the full value of their labour but also reduced them to instruments of production.

More importantly, Marx explained that this often created alienation, as workers no longer controlled what they produced and they became separated from the purpose and meaning of their work.

The capitalist system treated them as expendable, interchangeable parts within a machine.

Marx saw history not as the story of great individuals but as a process driven by material conditions.

Each historical stage depended on how societies produced and distributed goods.

He argued that once the contradictions of capitalism reached a critical point, the working class would develop the capacity to organise and overthrow the system.

As such, he believed that this change would lead to socialism, followed eventually by full communism, a society without class or state control.

Marx's growing political activism

After the revolutions of 1848 had begun, Marx returned to Germany and established the Neue Rheinische Zeitung newspaper in June 1848, which provided daily political commentary and called for democratic reform and workers’ rights alongside a demand to end the monarchy.

It became one of the few radical outlets at the time. Marx used it to articulate his vision of revolution, even as government forces pushed back against revolutionary efforts across Europe.

By May 1849, counter-revolutionary forces had regained control, and Marx faced exile once again.

He moved to London, where he spent the remainder of his life. There, he continued his activism by joining the First International, or the International Workingmen’s Association.

He wrote pamphlets, gave speeches, and corresponded with revolutionaries abroad, while he also fought heated arguments with other socialist thinkers.

Before his conflict with Mikhail Bakunin, Marx had already clashed with Pierre-Joseph Proudhon over the direction of socialist theory.

For example, his conflict with Mikhail Bakunin exposed major disagreements in socialist strategy.

Marx insisted on the need for a centralised revolutionary organisation and the temporary use of state power by the working class, while Bakunin favoured decentralised direct action and rejected the state altogether.

Their disagreements split the First International, though other factors contributed to its decline.

Marx’s influence, however, remained dominant in many workers’ movements.

Marx's other important written works

While living in London, Marx completed the first volume of Das Kapital, published in 1867.

The book was subtitled "A Critique of Political Economy" and examined the inner workings of capitalism using a mix of philosophy together with political economy and supported by historical examples.

It analysed how labour in relation to capital and commodities interacted to generate profit.

He argued that the competitive drive for profit led to the concentration of capital, instability in markets, and periodic economic crises.

Two additional volumes remained unpublished at the time of his death. Engels later compiled and released them using Marx’s extensive notes: Volume II in 1885 and Volume III in 1894.

Together, the three volumes formed a long critique of capitalism’s mechanics and contradictions.

In addition to Capital, Marx co-wrote The German Ideology in 1846, which outlined his view of historical development.

He also wrote The Critique of the Gotha Programme in 1875, where he criticised the moderate platform of the German Social Democratic Party, in which he warned against watering down revolutionary goals in favour of compromise.

Across his works, Marx presented capitalism as one stage in a longer historical process rather than as a natural or eternal system.

He aimed to expose its underlying logic and make visible the forces that would lead to its eventual collapse.

How his personal life influenced his work

Marx lived much of his adult life in hardship. His wife, Jenny von Westphalen, came from a noble background, but their marriage endured poverty and loss.

They raised seven children, but four died young. The surviving children often went hungry, and the family moved from one crowded London apartment to another.

Often, Engels had to step in with money. Even then, Marx frequently relied on pawnshops and borrowed funds to survive.

His health suffered from poor diet and stress, combined with long hours, during which he wrote.

Still, he continued his work, driven by the belief that his research would uncover the causes of the injustice he witnessed daily.

Those experiences sharpened his anger at capitalism’s failures because he saw poverty as a systemic consequence of private ownership and wage labour rather than as the result of misfortune or laziness.

He used his personal struggles as evidence of a broader social reality that millions endured.

Marx's later years and death

By the late 1870s, Marx’s health had declined sharply. He suffered from respiratory problems accompanied by liver issues and persistent fatigue.

His wife died in 1881, followed by his daughter Jenny the next year and the loss devastated him.

He had remained intellectually active an he had read books about anthropology, which he had annotated, and he had consulted works on history and mathematics, and he had shown interest in Darwin’s theory of natural selection, which he had seen as a parallel to his ideas on class struggle, but he had published little.

Marx died on 14 March 1883 at the age of sixty-four. His funeral at Highgate Cemetery was small, with less than a dozen people attended, including his daughter Eleanor and the socialist leader Wilhelm Liebknecht.

Engels, who delivered the eulogy, called him the greatest thinker of his time and predicted that his name would live on.

Eventually, it did. After 1917, revolutionaries in Russia used Marx’s theories as the foundation for the Soviet state, which was formally established in 1922.

Other communist movements across China, Cuba, Vietnam, and Eastern Europe adopted similar claims to his intellectual authority. However, their interpretations often diverged from his original works.

To this day, Marx continues to be one of the most studied and debated figures in history.

His theories continue to influence debates about class, power, economics, and the future of society.

However, many scholars continue to criticise his predictions or reject his conclusions, but some still find his analysis of capitalism useful for understanding inequality and social conflict.

Regardless, modern economists such as Thomas Piketty continue to engage with his ideas about capital accumulation and inequality.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.