The key thinkers of the Enlightenment and their revolutionary ideas

Across Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, philosophers and writers who promoted human reason and scepticism began to challenge the power of kings and churches and inherited traditions.

Known collectively as the Enlightenment, their ideas, which helped to change how many people understood society and scientific practice and the role of government.

Their influence often inspired revolutions, altered laws, and helped to change the rights of some individuals.

What was the Enlightenment?

The Enlightenment appeared during a period that included scientific breakthroughs, political tension, and growing literacy, particularly in Western Europe.

It lasted from approximately 1685 to 1815 and had generally drawn heavily on the work of the earlier Scientific Revolution.

Thinkers who took part in the movement encouraged more people to apply reason and careful questioning to many areas of life, such as religious belief, political life, and educational practice, and they rejected the idea that truth came from authority or tradition alone.

In cities such as Paris, London, and Berlin, new ideas began to spread more widely through books, newspapers, pamphlets, and salons, where writers and intellectuals debated philosophy and reform.

Influential salonnières such as Madame Geoffrin hosted gatherings that helped spread Enlightenment ideas to elite and educated audiences.

Enlightenment thinkers challenged forms of religious intolerance and royal absolutism and restrictions on information, and they argued that human progress depended on freedom of thought and open discussion.

As print culture expanded, so too did access to new ideas that called into question inherited power and inequality.

Governments often responded with censorship, imprisonment, or exile, yet Enlightenment writers persisted in their work and believed that knowledge should be shared rather than kept to themselves.

The movement produced a range of views. Enlightenment thinkers generally shared a belief that society could be improved through reforms in education and changes to the law that strengthened the protection of rights.

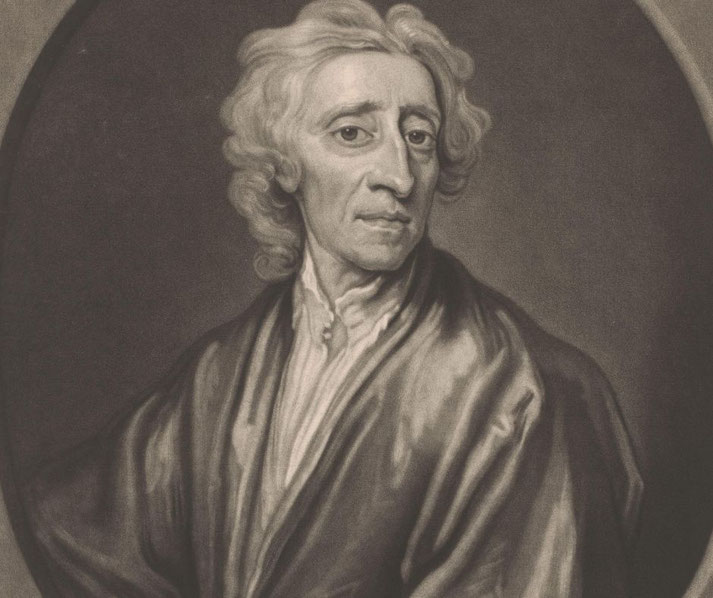

John Locke and the fight for natural rights

John Locke, who was born in 1632 in Somerset, England, developed a political philosophy that placed individual rights at the heart of just government, and he argued that the rights to life and liberty together with secure property rights were natural rights that belonged to all people rather than grants from rulers.

In his Two Treatises of Government, written in the aftermath of the English Civil War and published anonymously in 1689, Locke had firmly rejected the idea that kings ruled by divine right and had insisted that legitimate government could exist only with the consent of the governed.

According to Locke, individuals formed governments through a social agreement, giving up some freedoms in exchange for the protection of their rights, but he also believed that if rulers broke this agreement by abusing their power, citizens had both the right and the duty to remove them.

This principle helped to justify revolution in both theory and practice, and it often had a significant influence on political thinkers in Britain, America, and France.

He also served as secretary during the drafting of the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina in 1669, a document that had been prepared for Anthony Ashley Cooper.

Although Locke helped write the text, it included provisions such as hereditary nobility and protections for slavery that contrasted sharply with his later liberal principles.

Locke also contributed to theories of education and psychology, claiming in his Essay Concerning Human Understanding that the human mind began as a blank slate, or tabula rasa, and acquired knowledge through experience.

This idea supported Enlightenment optimism about human potential, since it implied that people could learn, improve, and reform both themselves and their societies.

Voltaire: Should we dare to speak freely?

François-Marie Arouet, who adopted the pen name Voltaire, used satire and wit to expose the injustice, superstition, and hypocrisy that he saw in the society of eighteenth-century France.

Voltaire, who was born in 1694, had frequently been targeted by censorship and imprisonment, and he became one of the most well-known voices of Enlightenment criticism, and his writings defended the principles of civil liberty and religious tolerance and freedom of speech.

In his Letters Concerning the English Nation, published in 1733 after he had been exiled to England from 1726 to 1729, and later released in France as Lettres philosophiques in 1734, Voltaire contrasted the religious freedom and limited monarchy of England with the repression of his native France, suggesting that political reform required not only courage but a commitment to reasoned debate.

He mocked clerical privilege and criticised the Church’s involvement in politics, yet he did not call for the end of religion itself, and he advocated a deist belief in a rational creator who did not interfere in human affairs.

Voltaire’s sharp pen and his persistent defence of intellectual freedom earned him both admirers and enemies, and his most significant effect was to argue that truth required open inquiry and that societies must protect the right to speak freely, even when those views offended the powerful.

His satire Candide, which was published in 1759, offered a sharp critique of optimism and religious cruelty through the famous refrain, “We must cultivate our garden.”

Why did Montesquieu believe power must be divided?

Charles-Louis de Secondat, better known as Montesquieu, studied law and observed the political institutions of Europe and concluded that the best safeguard against tyranny was the separation of powers.

In The Spirit of the Laws, which was published anonymously in 1748, he argued that liberty could survive only when distinct legislative and executive and judicial authorities operated independently and acted to restrain one another.

Montesquieu drew heavily on his observations of the English political system, where the monarch and Parliament and the courts functioned with separate responsibilities, and he applied this model to his theory that political power must be structured in such a way that no single person or group could dominate the others.

He warned that the concentration of authority in one set of hands inevitably led to oppression, and he maintained that political liberty required both legal guarantees and institutional limits.

Earlier, in his 1721 satire Persian Letters, he had also explored social and religious customs through the lens of fictional outsiders, which provided a clear critique of French society.

His influence affected constitutional theory in the United States, France, and elsewhere, and many later political systems adopted his principles by designing governments with separate branches and written limits on power.

In addition to his political ideas, Montesquieu also addressed issues of slavery and religious intolerance and the cultural variety of human societies, which he treated with a spirit of comparison of different societies that was common in Enlightenment scholarship.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau and the idea of the social contract

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who was born in 1712 in Geneva, developed a theory of government that combined a belief in human freedom with a concern for collective authority, and in The Social Contract, published in 1762, he set out his vision of a political order based not on divine right or hereditary privilege but on the collective agreement of free individuals.

Rousseau claimed that people had once lived in a state of nature where they enjoyed equality and independence, but that the emergence of private property had introduced inequality and conflict.

He proposed that a just society required a new social agreement, in which each person gave up certain personal freedoms to the general will, which expressed the common interest of the whole community.

For Rousseau, obedience to the general will did not reduce liberty but guaranteed it, since the laws represented not the command of rulers but the collective self-rule of the people.

The French and Genevan authorities had banned the book shortly after publication, which demonstrated the radical nature of his arguments.

Rousseau’s political thought had a major effect on both democratic and radical movements, particularly during the French Revolution, and his ideas also extended into education, where he promoted the idea that children learned best through experience and natural curiosity rather than strict discipline.

His belief that society had corrupted human nature and that moral development required participation in a community influenced later debates on citizenship and civic responsibility.

Immanuel Kant: The role of reason

Immanuel Kant, who was a philosopher from Königsberg, a city in the Kingdom of Prussia that is now known as Kaliningrad, Russia, was born in 1724 and believed that enlightenment meant the emergence from intellectual dependence and that reason alone could guide people toward moral and intellectual freedom.

In his famous 1784 essay What is Enlightenment?, he declared that individuals should “dare to know” and should use their own reason rather than relying on priests, monarchs, or tradition to think for them.

Kant argued that true moral action came from a sense of duty grounded in rational principles rather than from desire or fear, and he developed the idea of the categorical imperative, which required people to act according to maxims that could be universally applied.

For example, he believed that one should not lie, because a world in which everyone lied would collapse trust.

His approach to ethics treated all rational beings as ends in themselves, never to be used as means to an end, and his insistence on autonomy helped to define modern concepts of human dignity.

In both epistemology and political theory, Kant consistently upheld the idea that public debate and free expression were essential to human development, and he viewed reason as the tool that allowed people to escape ignorance and develop laws and institutions based on justice rather than authority.

Adam Smith’s ‘invisible hand’ and the birth of modern economics

Adam Smith, who was born in 1723 in Scotland, changed economic thinking by arguing that the pursuit of self-interest, when conducted in a competitive market, produced outcomes that benefited the whole society.

In The Wealth of Nations, which was published in 1776, the same year as the American Declaration of Independence, Smith explained that market forces operated without central planning and he used the metaphor of an “invisible hand” to describe the unintended social benefits that resulted from individual enterprise.

Smith criticised the mercantilist belief that governments should tightly control trade and accumulate precious metals, and he promoted instead a model of economic liberalism in which free exchange and competition and the protection of private property would create wealth more efficiently.

He supported limited state intervention, particularly in areas such as justice, defence, and education, but he warned against monopolies and corruption.

He had earlier held the Chair of Moral Philosophy at the University of Glasgow, where he developed many of his theories.

In his earlier work The Theory of Moral Sentiments, which was published in 1759, Smith also explored the moral dimension of human behaviour and he argued that people developed sympathy and a sense of justice through their social interactions.

His economic theory thus rested on both rational self-interest and the moral capacities of individuals to act with fairness and conscience.

Denis Diderot and the encyclopedia that changed the world

Denis Diderot, who was born in 1713 in Langres, France, led one of the most ambitious intellectual projects of the Enlightenment when he served as chief editor of the Encyclopédie, which had originally begun as a translation of Ephraim Chambers' Cyclopaedia, a large reference work that aimed to gather knowledge and present it in a way that encouraged critical thinking and scientific reasoning.

The Encyclopédie, which included contributions from dozens of writers such as Voltaire and Rousseau, appeared in thirty-five volumes between 1751 and 1772 and eventually contained more than 70,000 articles.

Diderot believed that knowledge should be widely available to everyone, not just to clergy or nobility, and he used the Encyclopédie to challenge religious dogma, political tyranny, and outdated superstition.

The articles covered a wide range of topics such as physics, law, history, agriculture, and manufacturing, and many entries contained critical messages that supported Enlightenment goals of liberty, equality, and progress.

Jean le Rond d'Alembert, who co-edited the early volumes, added mathematical and scientific expertise to the project.

Although the French government and the Church had tried to stop the publication, Diderot and his colleagues continued their work in secret, and copies of the Encyclopédie circulated widely across Europe.

Because the project made knowledge accessible and encouraged readers to question authority, it helped to spread Enlightenment values and reach readers outside academic circles.

Did the Enlightenment include women? Mary Wollstonecraft’s answer

Mary Wollstonecraft, who was born in London in 1759, issued a clear challenge to the exclusion of women from Enlightenment debates by insisting that reason and education should apply equally to both sexes.

In her Vindication of the Rights of Woman, published in 1792, she criticised the way women had been denied proper schooling and confined to roles of obedience and domesticity.

Wollstonecraft argued that women, like men, possessed the ability to reason and should be educated in order to become independent thinkers, moral citizens, and equal partners in marriage and society.

She criticised the social rules that encouraged women to focus on beauty and submission, claiming that these customs weakened both women and the society that relied on their moral influence.

Her earlier book, Thoughts on the Education of Daughters (1787), which had focused more on moral guidance and proper conduct for young women, helped lay the groundwork for her later arguments on equality and education.

Her work addressed both conservative thinkers who defended traditional gender roles and Enlightenment men who promoted liberty but ignored half the population.

When she demanded the same rights and responsibilities for women that Enlightenment thinkers promoted for men, Wollstonecraft created the basis for later feminist movements and education reforms.

Her daughter, Mary Shelley, would go on to author Frankenstein, continuing the family’s engagement with radical ideas.

How did Enlightenment thinkers inspire revolutions?

The Enlightenment helped to inspire the American and French Revolutions because it provided a new language for political reform, grounded in rights and equality and an emphasis on reason.

In 1776, the American Declaration of Independence echoed Locke’s theory of natural rights and asserted that government must protect life and liberty along with the pursuit of happiness.

The U.S. Constitution incorporated Montesquieu’s model of separated powers and established checks and balances to limit authority.

In France, revolutionaries read Rousseau’s call for the general will and Voltaire’s defence of freedom, and they used these ideas to dismantle monarchy, feudal privilege, and clerical authority.

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, which was issued in 1789 and was co-authored in part by Marquis de Lafayette in consultation with Jefferson, proclaimed that all citizens were equal before the law and that sovereignty belonged to the people.

Enlightenment ideas also influenced leaders in Haiti, Latin America, and other colonies who had used the language of rights and popular sovereignty to challenge imperial rule.

In Haiti, Toussaint Louverture emerged as a leader who had embraced Enlightenment ideals in his struggle against slavery and colonialism.

Across continents, the Enlightenment had become a source of inspiration for reformers who demanded freedom and justice and active participation in public life.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.