5 things you didn't know about the Australian Gold Rush

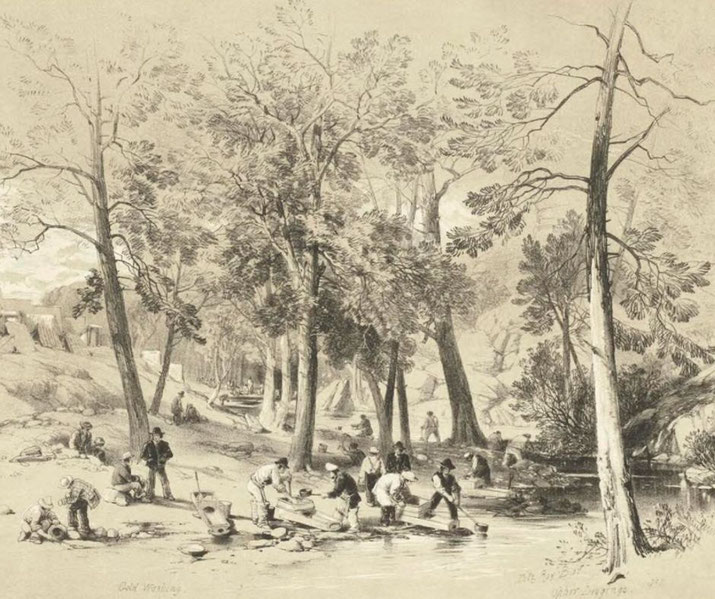

The Australian Gold Rush brought major change to the colonies from 1851 onwards. Thousands of migrants arrived, towns expanded rapidly, and colonial authorities struggled to manage the effects.

Beneath the surface of this well-known era, there were several surprising facts that showed how wide-ranging and significant the gold rush was.

1. The first gold rush was not in Victoria

The earliest major discovery of gold in Australia occurred in New South Wales rather than Victoria.

On 12 February 1851, Edward Hargraves identified alluvial gold at a site called Ophir, near Bathurst, after he returned from the Californian goldfields, where he became convinced that the terrain around the Macquarie River valley contained similar geological features.

Hargraves directed John Lister and William Tom, who physically discovered and extracted the first payable gold under his supervision.

People at the time argued that Lister and Tom deserved the credit, even though Hargraves received a government reward amounting to £10,000, which included a £2,381 lump sum and a £250 annual pension granted in 1877.

Within weeks, the colonial government in Sydney officially acknowledged the find, and a rush began that brought thousands of hopeful miners to the Central West region.

Earlier discoveries of gold during the 1840s had been kept secret by officials who feared economic instability and the loss of agricultural labour.

Once the Bathurst field had proven profitable, prospectors expanded their search into surrounding regions, and they reached as far south as Mount Alexander and Ballarat in Victoria by mid-1851.

Some historians argue that William Tipple Smith may have found gold as early as 1848, but his claim never received formal recognition.

Further finds at the Turon River and Sofala soon followed, and the spread of news across the colonies encouraged diggers from both within Australia and overseas to join the search for gold.

By the end of that year, New South Wales had issued hundreds of mining licences, and mining towns began to appear across previously remote parts of the colony.

The Bathurst Free Press played a major role in spreading reports of new discoveries, which had helped to fuel the growing excitement.

2. Chinese miners played a crucial role in the gold rush

Thousands of Chinese immigrants arrived in Australia between the early 1850s and 1870s, particularly in response to reports of gold discoveries in Victoria and New South Wales.

By 1858, the number of Chinese miners on the Victorian goldfields had exceeded 40,000, many of whom arrived through South Australia or the remote coastal town of Robe to avoid the discriminatory £10 poll tax introduced in 1855 by the Victorian colonial government that targeted Chinese arrivals.

The overland journey from Robe to the goldfields often exceeded 400 kilometres, and it could take weeks on foot.

Chinese miners typically worked cooperatively in large teams. They systematically reworked abandoned claims and washed gold from soil that European diggers had overlooked.

Their communities kept strict organisation, which included the provision of shared accommodation, food, medical care, and religious rites.

In many cases, Chinese miners brought with them mining experience from southern China, which they adapted to Australian conditions with notable success.

Tensions increased as resentment among European diggers grew in response to the efficiency and discipline of Chinese mining groups.

Violent incidents occurred on multiple goldfields, and the most well-known occurred at Lambing Flat in New South Wales during 1860 to 1861.

The largest riot occurred on 30 June 1861, when up to 2,000 European miners attacked Chinese camps and forced hundreds to flee.

Anti-Chinese sentiment spread through newspapers and political forums, which prompted demands for harsher restrictions and provided early justification for the development of racially exclusive immigration laws in the decades that followed.

The colonial government responded by introducing Chinese protectorate systems, such as that led by William Henry Foster in Victoria, though these efforts did little to reduce hostility.

3. Gold was not the only thing found

As diggers searched for gold across Australia’s interior, they often uncovered other mineral resources that would later support major mining industries.

In regions such as Broken Hill and Mount Isa, early prospectors noted the presence of lead, silver, copper, and zinc deposits.

Although these discoveries remained largely undeveloped during the initial gold rush years, they attracted commercial attention later in the nineteenth century, and they supported the growth of new industrial centres.

The silver-lead ore at Broken Hill, first recognised in the 1860s, became one of the richest deposits of its kind in the world by the 1880s.

In addition to mineral resources, some prospectors unearthed important fossil remains during excavations in ancient riverbeds and exposed sediment layers.

Early finds included the bones of extinct megafauna, fossilised plant matter, and marine invertebrates, which had helped Australian scientists trace the geological history of the continent.

Palaeontologists such as Gerard Krefft, curator of the Australian Museum in Sydney, used specimens collected from former goldfields to build some of the earliest scientific collections in colonial museums.

Among these were Diprotodon skeletons and other Ice Age fossils, though many early discoveries received poor storage or were dismissed due to a lack of knowledge of preservation.

The natural sciences benefited from the increased exploration, as surveyors, geologists, and naturalists travelled alongside miners to chart previously unrecorded areas.

Public interest focused on gold, and scientific discoveries had quietly accumulated, which provided long-term value to research institutions and contributed to the foundation of Australia’s modern mining and academic sectors.

4. It caused a population explosion

The discovery of gold triggered one of the most rapid population increases in Australia’s colonial history.

In 1851, the combined non-Indigenous population across all Australian colonies stood at around 437,000.

By 1861, it had reached nearly 1.2 million, according to colonial census figures that excluded Indigenous populations, due in large part to immigration from the British Isles, Europe, the United States, and China.

The lure of sudden wealth pulled families, single men, and entrepreneurs to the goldfields in numbers that colonial infrastructure struggled to support.

Victoria absorbed the largest share of this migration. With only 77,000 residents in 1851, the colony had risen sharply to over 538,000 within a single decade.

Immigration ships arrived daily in Melbourne at the height of the rush, particularly in 1852 and 1853, and temporary settlements such as Canvas Town appeared quickly to house the influx.

Melbourne, previously a modest town, expanded into a significant port city, and the volume of shipping traffic increased rapidly.

Colonial administrators raced to construct roads, bridges, railways, and telegraph lines to connect the goldfields to major towns and ports.

New settlements emerged around productive goldfields, and some, such as Ballarat, Castlemaine, and Bendigo, grew into permanent regional centres.

Local economies did well as businesses opened to serve the needs of miners and their families.

Newspapers, banks, schools, and courts appeared quickly, often within months of a rush beginning.

Those who failed to strike it rich often remained to take up farming, trades, or shopkeeping, which contributed to the permanent settlement of inland regions.

The Victorian gold export alone in 1852 exceeded £8 million, which helped to finance these changes and fuelled the colony’s rapid development.

Discontent on the goldfields also led to political change, most notably the 1854 Eureka Rebellion in Ballarat, where miners protested against the licence system.

5. The largest gold nugget was found in NSW

New South Wales produced one of the most remarkable discoveries in the history of gold mining.

On 9 October 1872, Bernhardt Holtermann and Louis Beyers extracted an enormous gold specimen from a quartz reef at Hill End.

The specimen weighed over 286 kilograms, and it contained around 93 kilograms of pure gold.

Although it was technically a gold-in-quartz specimen rather than a freestanding nugget, it remains the largest recorded gold-in-quartz specimen, and the largest true nugget, the Welcome Stranger, was found in Victoria in 1869 and contained nearly 71 kilograms of pure gold.

Holtermann became a prominent public figure, and he used his newfound wealth to support a number of public projects.

He funded the creation of a large photographic panorama of Sydney and the goldfields, which he showed internationally to promote immigration and investment in the Australian colonies.

The photographs, taken by Beaufoy Merlin and Charles Bayliss of the American & Australasian Photographic Company, later became some of the most valuable visual records of colonial life in the 1870s.

The Hill End discovery revitalised interest in the New South Wales goldfields at a time when attention had shifted towards Victoria.

It demonstrated that significant finds could still appear more than two decades after the first rush, and it helped extend the economic life of older mining regions well into the late nineteenth century.

Holtermann displayed the images at international exhibitions, including the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition in 1876.

The specimen was eventually broken up and smelted, and since no colour photographs exist of it, replicas and black-and-white prints preserve its memory as a reminder of Australia’s gold fever.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.