The ferocious and mysterious were-jaguar of the ancient Olmecs

Among the gods and supernatural beings that filled the world of the Olmec civilisation, one stood out for its strange appearance: the were-jaguar.

Artists carved it into stone and moulded in clay, but it always appeared as a creature with the snarling parts of a jaguar and the twisted body of a human.

Its image intrigued archaeologists from the moment the first Olmec sites were uncovered, and it has continued to cause debate over what it actually meant

Who were the Olmec?

The Olmec civilisation developed in the Gulf Coast region of Mexico, within the tropical zones of present-day Veracruz and Tabasco.

Archaeological evidence shows their presence from as early as 1600 BCE in earlier cultures, with the established civilisation thriving roughly between 1200 BCE and 400 BCE.

Scholars see them as the earliest known major civilisation in Mesoamerica. They failed to build an empire, but their influence reached distant parts of the region through trade routes and shared religious imagery.

Major settlements such as San Lorenzo, La Venta, and Tres Zapotes featured ceremonial platforms, very large sculptures, and an elite class that combined religious and political power.

The most striking examples of Olmec artistry are the very large basalt heads, some of which stand over two metres tall and weigh several tonnes.

Each head appears to show an individual with a unique face, which has led some researchers to suggest they were portraits of rulers or warriors.

Olmec craftspeople also made detailed jade figurines, ceremonial axes, and hollow clay statues that showed both human and supernatural forms.

Evidence from these sites includes symbols and objects that may represent an early calendar system and a form of writing, though scholars have not confirmed that either was fully developed or widely used.

Religious ceremonies were an important part of their society, and priests often held the authority to interpret omens, conduct sacrifices, and preserve order in the universe.

Bloodletting rituals and symbolic offerings were also surprisingly common. In some cases, human sacrifices appear to have been performed in connection with agricultural cycles or elite burials.

Later Mesoamerican cultures, including the Maya and Zapotec, would incorporate many of these ritual practices into their own religious systems.

What was the were-jaguar?

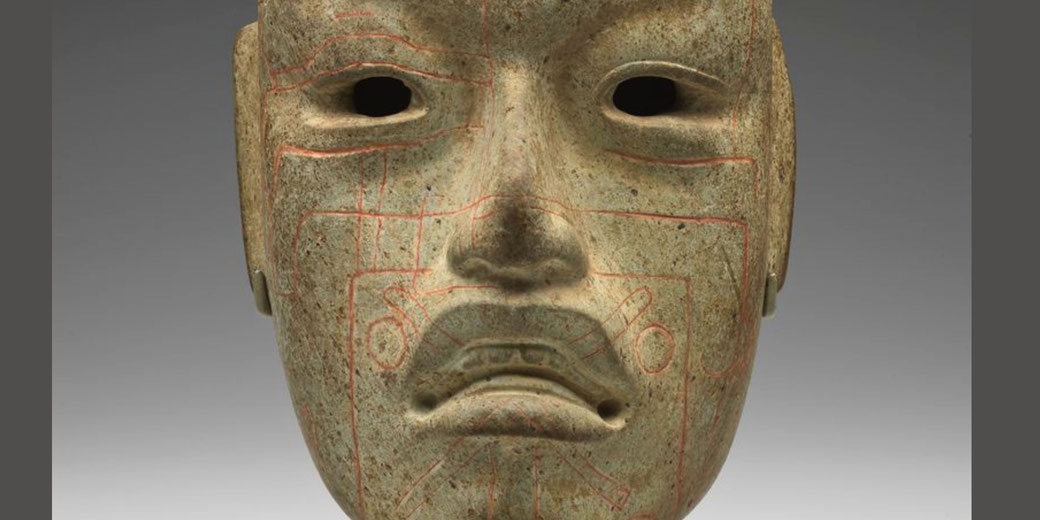

The were-jaguar appeared as a recurring and highly decorative figure in Olmec art.

It possessed the almond-shaped eyes, wide nose, and snarling mouth of a jaguar, but its head often showed a cleft or depression, and its body appeared distorted in ways that human anatomy could not explain.

Some representations included fangs, clawed hands, or overdone facial expressions.

These parts gave the creature an unnatural, almost spiritual quality.

In various scenes, craftspeople showed the were-jaguar as an infant held in the arms of adult figures, usually in ritual contexts.

In other examples, it took the form of a crouched or crawling figure, which craftspeople placed in positions suggesting pain, power, or transformation.

Some scholars have interpreted these images as symbolic of divine children, shamanic visions, or supernatural beings associated with rain, agriculture, or the underworld.

Jaguars held great significance across Mesoamerican cultures because their strength, nocturnal habits, and ability to move silently through the rainforest gave them associations with the spirit world.

The were-jaguar may have expressed the merging of human and divine traits, and it may have represented people believed to move between gods and humans.

Olmec rulers, who likely claimed divine ancestry, may have used the were-jaguar to legitimise their authority and connect their bloodlines to supernatural forces.

Artists showed the were-jaguar as a being instead of a literal creature that fused multiple identities and hinted at strange and magical forces.

Its distorted body parts and aggressive stance made it both awe-inspiring and unsettling.

Where has the were-jaguar been found?

Archaeologists have recovered were-jaguar figures from many Olmec sites, both large and small.

At San Lorenzo, numerous ceramic figurines and sculpted stone altars depict the creature with overdone parts and unnatural postures.

Some of these objects appeared in elite residences, while others were placed in ceremonial spaces.

Their distribution shows that the were-jaguar had importance across both public and private life.

La Venta, another major Olmec centre, contained some of the most elaborate images of the were-jaguar in large-scale art.

On Altar 5, a central figure cradles a were-jaguar infant as it comes out through what appears to be a cave-like opening, possibly meaning birth or ascension from the underworld.

As a result, caves held strong spiritual associations in Olmec belief, often as gateways between worlds.

Outside the core Olmec region, jaguar symbolism appears in many Mesoamerican cultures, but direct evidence of the distinctive Olmec-style were-jaguar design is less common.

Some jade carvings and stone masks from Oaxaca, the Valley of Mexico, and Chiapas include parts such as the cleft head and feline mouth, though scholars debate whether these reflect Olmec influence or parallel traditions.

The appearance of such motifs far from the Gulf Coast suggests that certain elements of the jaguar image formed part of a wider set of religious ideas.

Many of the finest examples have come from tombs, caches, and ceremonial platforms.

In these contexts, the presence of the were-jaguar confirmed its connection with elite status, religious roles, and divine claims.

The quality of work of these objects, particularly those made from jade, shows the high value placed on them by those who created and used them in rituals.

The deeper meaning behind the were-jaguar

The combination of human and feline parts suggested that certain individuals, such as shamans, rulers, or divine offspring, existed in a state outside usual life.

By associating themselves with the were-jaguar, the Olmec elite may have claimed authority in both the human realm and the spiritual one.

So, when Olmec artists created the were-jaguar, they may have intended to express the moment of becoming, when a human figure crossed into the spiritual world and returned altered.

Due to this, several scholars have proposed that the were-jaguar originated from shamanic ritual.

In this theory, a shaman would enter a trance, possibly caused by fasting, pain, or hallucinogenic plants.

During that altered mental state, the shaman might believe he had become one with a powerful animal.

As such, the distorted parts of the were-jaguar reflected that transformation.

Another interpretation suggests that the were-jaguar was the offspring of a human and a supernatural jaguar being.

This recurring visual theme supports the idea of a divine birth, where the child represented a new being who possessed traits from both parents.

The mythology behind such a birth may have formed part of ritual stories that people preserved and told through many generations.

Rather than depict everyday life or natural animals, Olmec artists chose to carve and paint this strange, terrifying creature again and again.

Its importance in religious centres, its appearance in funerary offerings, and its connection with elite figures all suggest that the Olmec people and gave physical form to the unseen forces they believed ruled their world.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.