Why crowds of people flocked to watch public executions throughout history

Modern people are always shocked to learn that, across the centuries, public executions drew large crowds who gathered to witness the final moments of a condemned individual.

It was a weird way for people to participate in a shared exhibition that fulfilled several odd purposes in pre-modern societies.

In fact, the reasons people came to watch ranged widely from moral instruction and entertainment to social pressure and even economic opportunity.

Reasons people attended public executions

In medieval Europe, public executions were held in town squares, marketplaces, or outside city gates.

These locations were chosen deliberately to increase visibility. Rulers and officials believed that executions acted as a discouragement, showing the results of criminal behaviour.

The logic was clear: when punishments were seen in public, others might fear committing similar crimes.

Whether it involved hanging, beheading, burning, or drawing and quartering, the method of execution was often designed to make a lasting impression.

For example, the execution of William Wallace in 1305 included hanging, emasculation, disembowelment, and the scattering of body parts across different cities in England and Scotland.

His head was displayed on London Bridge, and his quarters were reportedly sent to towns such as Newcastle and Berwick, though exact locations remain uncertain.

The brutality reinforced state power and intended to discourage treason.

At the same time, religious structures encouraged attendance. In Christian societies, death was considered a crucial moment in the journey of the soul.

A public execution allowed observers to see whether the condemned repented, confessed, or accepted divine judgment.

Clergy often accompanied prisoners to the scaffold, and they offered prayers and urged confession.

In the early modern period, pamphlets which detailed the crimes and final words of the condemned were sold to onlookers, and they framed the execution as a warning story.

These broadsheets, such as "The Last Dying Words and Confession of John Smith," often blended fact and moral fiction, becoming part of a growing print culture in 17th and 18th century England.

Entertainment aspects of public executions

For many, the execution was an acceptable form of entertainment. Before the rise of professional theatre and mass media, such public spectacles filled a gap in community life.

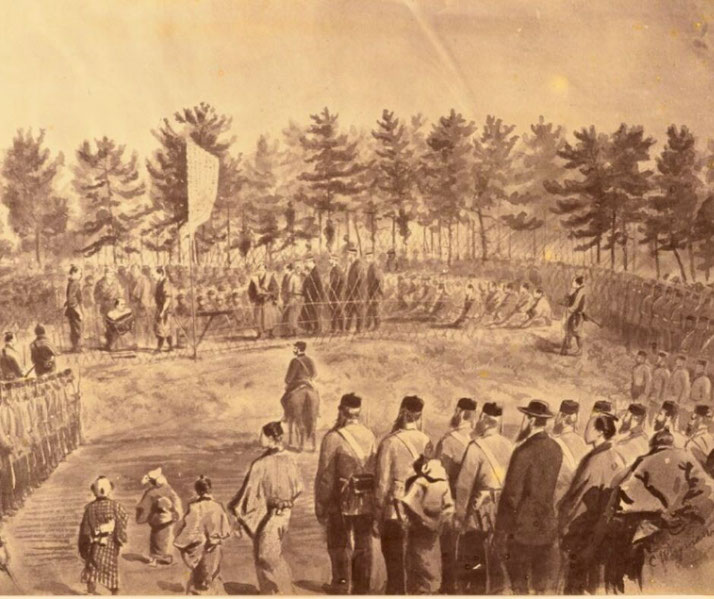

In 18th century London, thousands of people would line the streets to watch cart-processions of condemned prisoners from Newgate Prison to Tyburn.

The event became a festive occasion: vendors sold food and alcohol, and some spectators reserved rooftop seating in advance.

Others climbed trees or lamp-posts to secure a better view. The crowd included men, women, and children and, as such, the atmosphere often looked like a fairground.

The most well-known executions, such as that of the pirate Captain Kidd in 1701 or highwayman Jack Sheppard in 1724, attracted large audiences and were discussed for weeks afterward.

Although Kidd was executed at Execution Dock in Wapping rather than Tyburn, the event still drew a significant crowd.

The triangular Tyburn Tree could hang multiple victims at the same time, and the slow procession through the streets was part of the formal drama.

In addition, public executions strengthened the existing social order. Spectators who witnessed the punishment of criminals, many of whom were poor and left out or had been accused of threatening authority, were reminded of the boundaries that maintained law and social ranking.

In France under the Ancien Régime, nobles were usually spared public humiliation because they received swift and private deaths, whereas peasants were subjected to long and painful executions in crowded places.

In England, similar differences existed; nobles were often beheaded with a sword or axe, while commoners were hanged in public.

Simply, these events reaffirmed who had the power to take life and who did not.

There were also practical motives. In many societies, people were legally or socially obliged to attend.

In colonial America, laws sometimes required the presence of local citizens at executions.

In Massachusetts Bay Colony, failure to attend could arouse suspicion or be seen as defiance of community rules.

In other cases, employers closed businesses so workers could witness the hanging.

Over time, the habit of watching executions became part of local custom, and certain towns became known for the scale and eagerness of their execution-day crowds.

Decline of public executions in the 19th century

By the 19th century, attitudes toward public executions began to shift as reformers argued that public hangings encouraged rowdy behaviour, emboldened criminals, and made people less sensitive to violence.

British MPs such as William Ewart called for change, and in 1868, Britain held its last public execution. Other nations followed.

By the early 20th century, most Western countries had moved executions behind prison walls or abolished them entirely.

Even so, large crowds continued to gather outside prisons during scheduled executions, so that they could hear details or witness a moment of reckoning.

In 1927, the execution of Sacco and Vanzetti in the United States drew crowds of both supporters and protesters who held vigils and awaited news through the night.

Most accounts focused on mourning and public protest rather than celebration.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.