Why the Aztec capital city of Tenochtitlan was truly remarkable

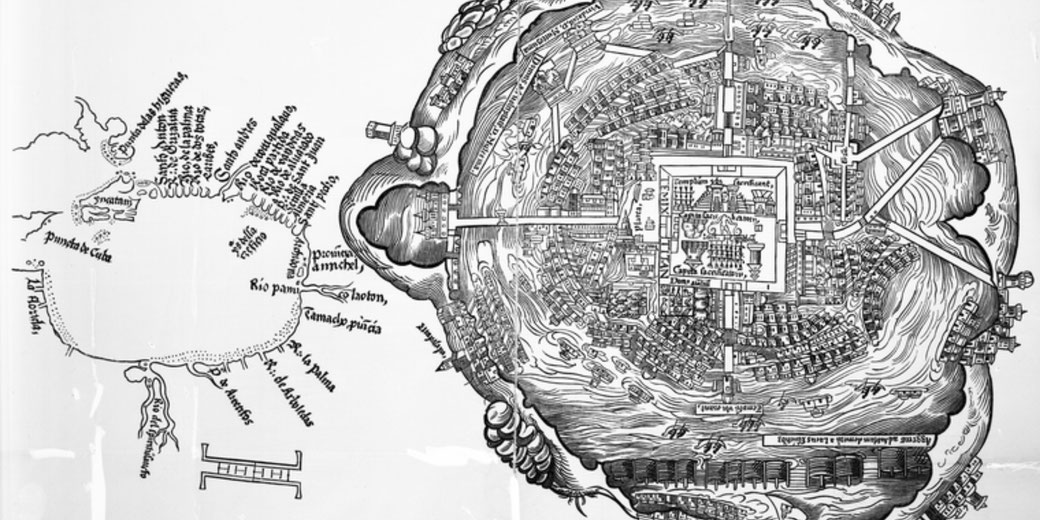

Surrounded by the waters of Lake Texcoco, a city appeared in the 14th century that defied the challenges of geography.

Built on a series of islands and connected by massive causeways and canals, it combined complex urban planning with spiritual vision on an astonishing scale.

Towering temples, bustling marketplaces, and floating gardens all created by a civilization confident in its power and deeply attuned to the rhythms of nature and the cosmos.

Why did the Aztecs build their city on a lake?

In 1325, a group of Nahuatl-speaking people known as the Mexica arrived in the Valley of Mexico after years of migration.

They believed they had found their new homeland when they witnessed an eagle perched on a cactus that gripped a snake in its talons.

The location lay on a marshy island in the middle of Lake Texcoco, a site most other groups had ignored due to its unsuitable conditions.

Although the ground was covered in shallow water and reeds, they viewed the site as a place chosen by the gods.

For the Mexica, religious conviction might have explained their choice, but the site also offered clear advantages for defence.

The surrounding lake created a natural moat that helped them protect themselves against enemy groups in the Valley of Mexico.

On each causeway, removable bridges provided control over entry points, which made the city easier to defend.

Also, canoes moved freely between the city and nearby communities, which made it possible to run trade routes and keep supplies of goods steady.

Over time, three main causeways connected Tenochtitlan to the mainland: one toward the north shore near Tepeyacac, another to Iztapalapa in the south, and a third westward to Tlacopan.

Thanks these conditions, Tenochtitlan developed into a centre of military and political power.

Once they secured their position, the Mexica expanded their control over neighbouring settlements and they collected tribute and made alliances that strengthened their hold on the valley.

Ingenious solutions: How the Aztecs turned water into land

With limited land available for farming, Aztec engineers developed chinampas, which were man-made plots created from woven mats and layers of earth.

They anchored the mats with wooden stakes and allowed lake vegetation to take root, which held the platforms in place.

Farmers used canoes to move between the plots, and they used mud from the lake bed to keep the soil rich.

One hectare of chinampa could yield four to five crops per year, and in some cases as many as seven, which made it one of the most productive agricultural systems in the pre-modern world.

As well as expanding farmland, the Mexica expanded the city's land as builders filled shallow sections of the lake with stones, mud, and rubble to form solid ground.

Over time, entire neighbourhoods grew from the lakebed, linked together by canals and walkways.

Each district had a mix of homes, gardens, and temples. Spanish friar Diego Durán later described these watery streets as busy with traffic, with some canals wide enough for two canoes to pass side by side.

To secure fresh water, engineers constructed two major aqueducts at different times, which carried water from the springs at Chapultepec.

Clay pipes and wooden channels carried water across the city, while dikes and levees separated fresh water from salty lake water.

The Nezahualcoyotl dike, completed around 1449 through a joint effort between Nezahualcoyotl of Texcoco and the Mexica leadership, helped prevent flooding and protected chinampa zones from saltwater that seeped in.

During heavy rain, floodgates and drainage canals controlled the rise in water levels and prevented damage to homes and crops.

As a result of these combined efforts, the Aztecs turned a marshy island into an urban environment that kept order and produced consistent harvests.

Their control over water, land, and agriculture allowed the city to support a large population and a social structure with many layers.

A marketplace like no other: The bustling trade of Tlatelolco

Among the most important features of the city was the market at Tlatelolco. Each day, tens of thousands of people visited the plaza to trade goods that came from every region of the empire.

Eyewitnesses such as Bernal Díaz del Castillo described it as larger and better run than anything they had seen in Europe.

Vendors arranged their stalls into distinct sections, and officials watched all deals to make sure they were fair.

When the Spanish visited the market in November 1519, they estimated that up to 60,000 people could gather on peak trading days, though modern scholars suggest somewhat lower numbers.

During long-distance expeditions, the pochteca, the professional merchant guilds, travelled to distant provinces and other lands to gather valuable materials.

They brought back obsidian, cacao, turquoise, salt, copper bells, cochineal dye, tobacco, and tropical feathers.

Many of them also acted as spies and messengers, and they reported on political events outside the empire’s centre.

In the market itself, the layout showed careful organisation. Sections of the plaza were reserved for food, tools, textiles, and fine goods.

Cacao beans, cotton cloth, and quachtli bundles were used as currency, and standard weights kept measures the same.

Judges, scribes, and guards kept order even on the busiest trading days.

Why the Spanish were amazed by Tenochtitlan

Upon their arrival in 1519, Hernán Cortés and his men found themselves stunned by the city's scale and by an orderly layout that framed canals and courtyards.

In his letters to Charles V, Cortés compared the city to Seville, but insisted that its canals, bridges, and neat layout surpassed anything he had seen in Spain.

As he crossed the causeways and entered the central area, he recorded wide streets, clean water channels, and rows of well-built homes.

The Spanish chronicler Andrés de Tapia confirmed these observations, noting the city's very large scale and precision.

At the centre of the city stood the Templo Mayor, a twin-pyramid complex dedicated to Huitzilopochtli and Tlaloc.

There, priests climbed its steep stairs to perform sacrifices and offer prayers during festivals and military victories.

Around the temple, a sacred enclosure contained shrines, schools, and ceremonial spaces reserved for the high-ranking priesthood.

Inside the palace of Moctezuma II, Spanish observers found animal enclosures, bird enclosures, collections of codices, and plant gardens.

Nobles wore clothes woven from fine cotton and decorated with bright feathers, while attendants swept the streets and kept public order.

Aqueducts brought clean water into private homes and fountains, and waste was removed daily by organised work teams.

Moctezuma II, who ruled from 1502 to 1520, maintained a court that matched any royal household in Europe.

When they saw such organisation, the Spanish found their expectations changed completely.

They had prepared for a scattered village, but instead found a planned large city with a population that may have been over 200,000.

This made it one of the largest cities in the world at the time, matched only by cities such as Paris, Constantinople, and Beijing.

The experience left them both impressed and jealous, which soon contributed to their aim to control the city and take its wealth.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.