Seppuku: The ultimate samurai sacrifice

Seppuku was a form of ritual suicide by disembowelment that allowed a warrior to preserve honour when facing shame, failure, or inevitable capture.

It was expected to be executed with ritualistic care, which meant that it was seen as an affirmation of a warrior’s character.

People even chose to witness each meticulous detail, from the blade’s edge to the recitation of farewell lines.

But what made the samurai choose to do this?

Preparation for Seppuku

Known in the West as hara-kiri, seppuku had its origins in the twelfth century during the late Heian period, before the establishment of the Kamakura shogunate in 1192, when the samurai class became important as military retainers of powerful lords.

The Heike Monogatari recorded early instances in which warriors committed seppuku in the Genpei War, and Minamoto no Yorimasa’s death in 1180 became one of the earliest well recorded examples of this ritual.

However, some sources suggest that Minamoto no Tametomo may have performed a form of ritual self-disembowelment even earlier, around 1170.

During an age in which warfare was foundational to political power, the concept of dying with honour became very important for a social class that defined itself through loyalty and service.

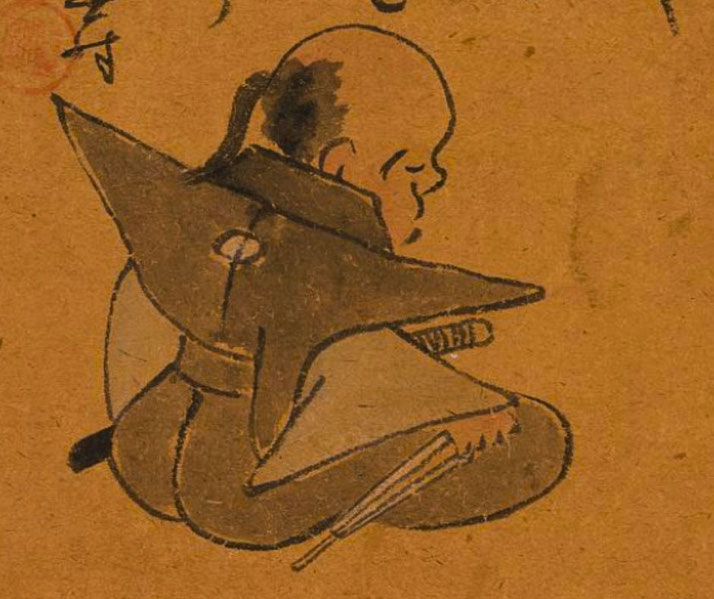

In preparation for seppuku, a samurai followed a strictly prescribed process.

Before the act, he prepared himself mentally and spiritually and often composed a death poem known as a jisei that expressed acceptance of fate.

In white robes, which symbolised purity, he sat formally on his knees in the seiza position, with a short sword or dagger called a tanto or wakizashi placed in front of him.

After opening his kimono, the warrior gripped the blade with both hands and cut into his abdomen from left to right, sometimes adding a second vertical cut.

The role of the kaishakunin, a second individual who would decapitate the samurai to prevent prolonged suffering, developed later and became a formal part of the ritual in subsequent centuries.

From the earliest accounts of the Genpei War in the late twelfth century, warriors took their own lives in this way when defeat became inevitable.

Over time, seppuku developed into a formal act that also functioned as a legal punishment for high-ranking samurai.

Under the authority of a daimyo or shogun, a retainer might be ordered to commit seppuku as an honourable alternative to execution.

Formal ceremonies included witnesses and officials who recorded the event. In records from the Edo period, condemned samurai were often allowed to end their lives in this way rather than face the shame of public beheading.

Tokugawa ritual adaptation

As time passed, feudal law codes and manuals of warrior conduct such as the Bushido ethos supported the practice.

Honour guided the life of a samurai in every respect, and he also upheld loyalty and duty.

As a demonstration of these values taken to their final outcome, seppuku could also act as a protest against an unjust superior or as an expression of remorse for failure in battle or duty.

In 1701, the famous case of Asano Naganori illustrated the powerful association between loyalty and honourable self-sacrifice.

After attacking a court official in Edo Castle, Asano was ordered to commit seppuku, and in 1703 his retainers avenged his death in the celebrated episode of the Forty-seven Ronin.

In the nineteenth century, the practice declined as Japan underwent major political and social change.

Eventually, following the Meiji Restoration of 1868, the government ended the samurai class along with the feudal order all together.

In 1873, seppuku was officially banned as part of modernisation changes, yet the practice continued to hold cultural significance as an important symbol of loyalty and honour.

Even after the ban, rare examples occurred, including the suicide of General Nogi Maresuke in 1912 following the death of Emperor Meiji and the actions of several officers who performed seppuku during the final stages of World War II.

Oddly, in 1970, the writer Yukio Mishima staged his own seppuku in protest against the direction of modern Japanese society.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.