How did Christianity change from a persecuted minority to the largest religion in the world?

What began as a radical new interpretation of Jewish belief on the edges of the Roman Empire would grow into a global force that reshaped law codes and influenced how people lived.

Yet, somehow, this unpopular movement from Jerusalem with very little political support ended up being on the most potent factors in the rise of Western civilisation over the next 1000 years.

How Christianity began

Christianity began in the early first century AD as a small Jewish group in the Roman province of Judea.

It centred on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth, a Jewish preacher who attracted a following by speaking about the coming kingdom of God, healing people, and challenging the power of the religious leaders.

His message appealed to those who felt cut off from traditional Jewish leaders or oppressed by Roman rule. Jesus taught between approximately 27 and 33 AD.

After Jesus was executed by crucifixion under the Roman governor Pontius Pilate, his followers claimed that he had risen from the dead on the third day.

They spread this message as proof that Jesus was the Messiah promised in Jewish writings and that salvation was now available to all, not just Jews.

Early followers included figures such as Peter, James, and Mary Magdalene, who was a strong supporter of Jesus.

The early Christians believed they were living in the last days and saw themselves as part of a growing group preparing for God's final judgement.

They met in private homes, shared meals, and rejected the worship of Roman gods.

Their refusal to take part in traditional Roman religious ceremonies brought them into conflict with local authorities.

Most of the earliest converts were Jews, but over time, more Gentiles joined the group.

The travels of apostles such as Paul of Tarsus spread Christianity into Greek-speaking cities across the eastern Mediterranean, especially between c. 46 and 60 AD.

By the end of the first century, Christian groups could be found in cities like Antioch, Ephesus, and Rome.

Antioch was the first place where followers were called "Christians," as recorded in Acts 11:26, though the name was likely made up by outsiders.

Paul's letters, especially those to the Romans, Corinthians, and Galatians, were read aloud in churches, and they helped make beliefs more consistent.

How it gained followers in the Roman Empire

Christianity’s appeal lay in its promise of salvation for all and the importance of personal restraint.

In a society with sharp social divisions and cruelty, the Christian promise of salvation for the poor, slaves, and women was powerful.

Christians also cared for each other, especially in times of famine or plague, and this sense of looking after one another helped build strong community bonds.

As Christian groups became more organised, bishops appeared to lead congregations and settle arguments, which gave the faith more structure.

The letters of Paul and other early texts were passed between communities, which made teachings more consistent.

Roman officials saw Christianity as a dangerous and suspicious group because it refused to honour the emperor as a god and rejected the public religious duties that were seen as necessary for the good of the empire.

Attacks on Christians happened from time to time, especially under emperors like Nero in 64 AD, Decius in 250 AD, and Diocletian in the early fourth century.

In c. 112 AD, Pliny the Younger wrote to Emperor Trajan for advice on how to deal with Christians in his province.

However, these efforts to stop Christianity often had the opposite effect. Stories of martyrs gained respect and strengthened the faith of believers.

By around 300 AD, Christians may have made up as much as 10% of the Roman population, though estimates differ.

Christianity’s slow and steady spread through cities, trade routes, and the lower classes allowed it to grow under the radar of much of the Roman upper class until it had already become widespread.

Becoming the only religion of the empire

The key moment came in the early fourth century when Emperor Constantine claimed to have seen a vision before the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in 312 AD.

He told his troops to fight under the sign of the Christian cross and won the battle.

The next year, the Edict of Milan, issued by Constantine and Licinius in 313 AD, gave religious freedom to all faiths, including Christianity.

Constantine began to support Christians at court and paid for the building of churches, such as the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem.

He called the Council of Nicaea in 325 AD to fix arguments within the Church, especially the nature of Christ, which led to the creation of the Nicene Creed and the rejection of Arianism.

The Creed was later updated at the Council of Constantinople in 381 AD.

By the end of the fourth century, under Emperor Theodosius I, Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire through the Edict of Thessalonica in 380 AD.

Pagan worship was banned, temples were shut, and Christian bishops gained political power.

The Church began to take over city jobs, such as giving out food and organising charity.

This change from a persecuted minority to a state-supported religion gave the Church a level of power it had never had before, but it also created internal problems.

Church leaders now had to deal with politics, money, and competing groups with different beliefs, which led to new tensions and rivalries.

The fall of the Roman Empire and the rise of the Church

When the Western Roman Empire fell apart in 476 AD, the Church remained one of the few stable institutions.

Roman cities broke down, trade slowed, and political power split into local kingdoms, but the bishop of Rome, later called the pope, continued to lead Christians across Western Europe.

For example, Pope Leo I met with Attila the Hun in 452 AD. This meeting showed the growing influence of the papacy, though the reasons Attila withdrew remain unclear.

The Church kept Latin reading and writing, saved books, and trained officials who worked with new rulers.

Monasteries became centres of learning, farming, and charity, helping to keep Christian ideas alive during a time of great disorder.

The Rule of St. Benedict was written around 530 AD and became the guide for life in monasteries, especially at places like Monte Cassino.

In the east, the Byzantine Empire stayed strong under emperors who saw themselves as protectors of Orthodox Christianity.

The emperor and patriarch of Constantinople worked together to support religious unity, even as arguments about Christ’s divine nature caused problems.

The Iconoclast Controversy, which lasted from 726 to 843 AD, was one of the most bitter.

Meanwhile, in the west, the pope slowly gained more power and freedom. This was most visible in events such as the crowning of Charlemagne as Holy Roman Emperor in 800 AD, which showed the pope’s claim to have control over Christian kings and rulers in the West.

The Church turns on itself: The Great Schism

In 1054, centuries of growing tension between the Eastern and Western Churches ended in each side rejecting the other, an event known as the Great Schism.

Differences in beliefs, power, and traditions had caused a deep split between the Latin-speaking West and the Greek-speaking East.

Arguments about who held ultimate authority and how religious rituals were carried out, including the use of flat bread in communion, all played a part in the break.

The leaders involved were Pope Leo IX and Patriarch Michael Cerularius. The Eastern Church became known as the Orthodox Church, while the Western Church became known as Roman Catholic.

The schism weakened Christianity’s unity and made it hard to work together during major events such as the Crusades.

When Western crusaders attacked Constantinople in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade, the two sides of Christianity were divided for good.

Though some efforts were made to fix the split, both sides stayed strong in their own teachings and leadership.

Now the Christian world had two rival centres of power: Rome and Constantinople. Each claimed to be the true leader of Christianity.

The mutual excommunications were not officially ended until 1965 by Pope Paul VI and Patriarch Athenagoras.

The Great Schism was not the end of Christian fragmentation. In the centuries that followed, further splits occurred, particularly in the Western Church.

Fragmentation in the West: The Protestant Reformation

In the sixteenth century, Western Christianity faced a crisis from within. Many ordinary people and priests were angry about the Church’s growing wealth and the misuse of its power.

The sale of indulgences, the power of the pope, and the lack of access to scripture in local languages all caused anger.

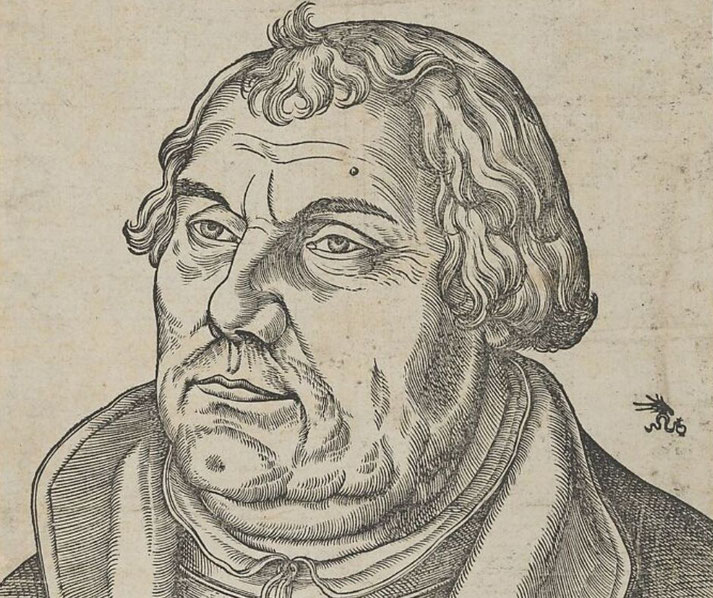

In 1517, Martin Luther, a German monk, nailed his Ninety-Five Theses to the door of a church in Wittenberg.

He called for reform, stressed salvation through faith alone, and rejected the pope's power. They spread quickly due to the printing press.

Luther’s actions began a wave of religious reform across Europe. Reformers such as John Calvin in Geneva and Huldrych Zwingli in Zurich developed new teachings and Church structures.

The Protestant Reformation broke Western Christianity into different groups: Lutheran, Calvinist, Anglican, and others.

Wars of religion followed, and political leaders often used these splits to break away from the pope.

The Catholic Church answered with the Counter-Reformation, which began with the Council of Trent, held from 1545 to 1563, restating older teachings and fixing problems inside the Church.

Europe would never again have a single religious leader.

Christianity's struggles and success in the modern era

From the seventeenth century onwards, Christianity had to adjust to a changing world.

The Scientific Revolution and Enlightenment challenged church authority, especially in Protestant areas.

Ideas about reason, freedom, and personal choice reduced the role of churches in public life.

In Catholic countries, governments slowly took control of Church property and education.

However, Christianity also spread around the world through European colonisation.

Missionaries brought Christian teachings to the Americas, Africa, Asia, and the Pacific, often alongside imperial conquest.

In the twentieth century, Christianity faced more tests. World wars, secular ideas, and globalisation challenged its ability to stay important.

Yet it also grew in places outside Europe. Christianity expanded quickly in sub-Saharan Africa, South Korea, and Latin America.

New forms of Christianity, such as Pentecostalism and evangelical movements, attracted millions of followers.

Well-known figures included Billy Graham and William J. Seymour. In many Western countries, regular church attendance fell, but Christian ideas still played a role in political debates and cultural values.

In Communist countries like the Soviet Union and Maoist China, Christianity was controlled or banned.

It continued to be the largest religion in the world by number of followers, with about 2.3 billion people.

How can the growth of Christianity be explained?

Christianity’s growth can be explained by a combination of long-term developments and the influence of political forces.

Its early focus on self-control, care for the poor, and universal salvation helped it stand out in the Roman world.

The willingness of its followers to suffer and die for their beliefs gained respect and loyalty.

Once it became connected to government power, it had the money and strength to grow across Europe.

The Church’s involvement in education and its control of public life allowed it to become part of daily life during the Middle Ages.

Later, Christianity’s spread through European colonisation and missionary work introduced it to new continents.

Its flexibility allowed it to grow in different cultures and languages. New types of Christianity offered a variety of beliefs and worship styles, which appealed to many different people.

Even as secularism grew in some places, the continued growth of Christianity in the global South kept it strong.

From small beginnings in Judea to becoming a global religion, Christianity’s spread was not caused by one thing but by many changes that matched the needs of different societies over two thousand years.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.