What did Commodore Perry want from Japan?

The arrival of Commodore Matthew Perry in Japan in 1853 created a turning point in East Asian diplomacy. For over two centuries, Japan had maintained a policy of national seclusion (sakoku), which strictly limited foreign contact and trade.

Perry’s expedition, backed by the growing industrial and naval power of the United States, sought to break this isolation and establish formal relations between the two nations.

America and Japan in the 19th century

During the first half of the 19th century, the United States rapidly expanded its land holdings and economic goals.

Following the annexation of California in 1848 and the discovery of gold there the same year, American merchants and officials became increasingly focused on securing reliable sea routes to East Asia.

Trade with China had already become a priority, and Japan, positioned strategically between North America and the Asian mainland, presented a valuable waypoint for refuelling and resupply.

At the same time, American whaling vessels operated throughout the Pacific and often faced problems when shipwrecked or needing provisions near Japan.

Japanese coastal communities, which followed official policy, often refused assistance or detained foreign sailors.

These incidents gave American politicians a humanitarian reason to demand changes in Japanese policy.

Alongside economic and strategic concerns, the United States presented its interest in Japan as a moral obligation to protect its sailors and promote friendly international relations.

The advent of coal-powered steamships further increased the need for reliable coaling stations across the Pacific, intensifying the strategic value of Japanese ports.

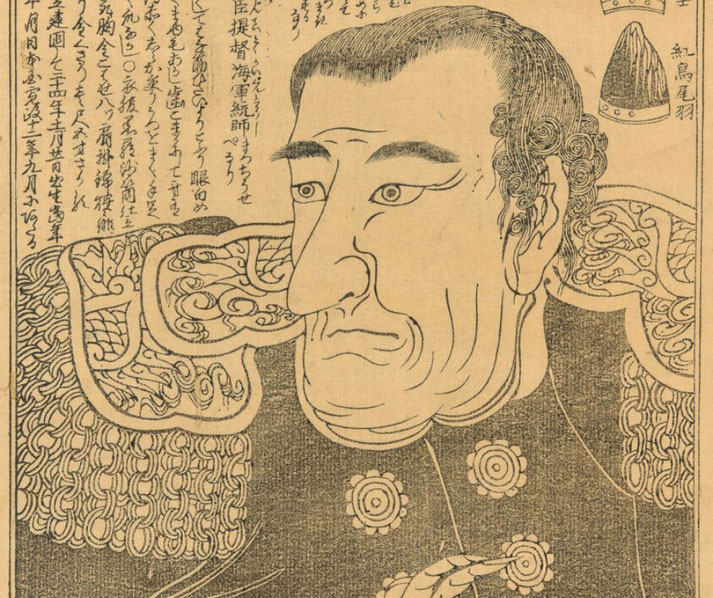

Commodore Perry: The man and his mission

Born in 1794, into a naval family, Matthew Perry held extensive experience in maritime operations before he was chosen to lead the expedition to Japan.

By the time of his appointment in 1852, he had served in conflicts such as the War of 1812 and the Mexican–American War, and had advocated for naval modernisation and steam power.

Perry’s selection for the Japan mission showed his reputation for discipline and strategic thinking, which were complemented by his knowledge of naval warfare and international diplomacy.

Perry’s instructions from President Millard Fillmore and originally from Secretary of State Daniel Webster were exact.

However, by the time of his departure, Edward Everett had succeeded Webster and issued the final orders.

Perry was to get a treaty that promised kind treatment of shipwrecked American sailors, allowed U.S. vessels access to Japanese ports for coal and supplies, and opened at least one port for limited trade.

He was told to act peacefully but firmly, and to convey American intentions through a demonstration of naval power if necessary.

Perry believed that Japan would not respond to soft diplomacy and planned his arrival with a deliberate display of strength, which exemplified gunboat diplomacy.

The American arrival in Japan

When Perry sailed into Edo Bay in July 1853, he arrived with four modern warships, including the steam-powered USS Mississippi, which dwarfed the traditional Japanese vessels stationed nearby.

Only two of the four ships, the Mississippi and Susquehanna, were steam-powered, which highlighted America’s technological edge.

His arrival caused panic among the Tokugawa authorities, who had no set procedure for dealing with such a direct and strong foreign demand.

He refused to engage with lower officials and insisted on presenting President Fillmore’s letter directly to a high-ranking representative of the shogunate.

The letter had been carefully prepared in English, Dutch, and Chinese, languages the Japanese were familiar with through their scholarly and diplomatic experiences, though its contents were met with suspicion and unease.

The shogunate eventually sent Hayashi Akira, a senior scholar-official, to receive the letter.

The broader response to Perry’s demands was managed by Abe Masahiro, the chief senior councillor (rōjū) of the Tokugawa government, who faced considerable internal disagreement over how to proceed.

In a move without precedent, Abe asked over sixty domain lords for advice, which revealed uncertainty within the regime.

After he handed over the letter, Perry departed with a warning that he would return for an official reply.

True to his word, he reappeared in February 1854, this time with an even larger fleet of seven ships.

Although the ships were not identical to those in the earlier journey, Perry’s strengthened naval presence further supported his intentions.

Over several weeks of tense negotiations, the Japanese unwillingly agreed to terms.

The result was the Treaty of Kanagawa, signed on 31 March 1854 aboard the USS Powhatan.

It opened the ports of Shimoda and Hakodate to American ships, promised assistance to shipwrecked sailors, and permitted the future establishment of a U.S. consulate at Shimoda.

The treaty was Japan’s first formal diplomatic agreement with a Western power, unlike earlier arrangements with the Dutch that had not involved formal treaties.

Did Perry achieve all of his objectives?

Although Perry did not secure full commercial access or a broad trade agreement, he accomplished the primary goals set by his government.

The treaty opened Japanese ports for limited resupply and created the framework for future diplomatic relations.

It also granted Americans preferential treatment in coastal emergencies and established a model for Western engagement with Japan.

Perry had also hoped to establish strong long-term influence for the United States in East Asia.

In the short term, his mission succeeded and positioned the U.S. ahead of European powers that had also sought access to Japan.

Within a few years, Britain, Russia, and the Netherlands secured similar agreements, but Perry had ensured that the United States acted first and on its own terms.

He returned to the United States in 1855 and published an account of his journey, which emphasised both the skill of his strategy and the perceived necessity of American expansion.

The impact on Japan

Perry’s journey disrupted the Tokugawa shogunate’s policy of seclusion and exposed internal divisions among Japan’s ruling elite.

Although the Treaty of Kanagawa appeared modest, it set in motion a chain of events that would lead to further treaties, the loss of tariff control, and growing dissatisfaction among samurai and intellectuals.

Many Japanese began to question the ability of the shogunate to defend national sovereignty, and the sense of humiliation contributed to political unrest.

Among the more vocal opponents of foreign influence were advocates of sonnō jōi, who urged reverence for the emperor and the expulsion of foreigners.

Over the next fifteen years, Japan experienced growing pressure from foreign powers and internal calls for reform.

By 1868, the Meiji Restoration replaced the Tokugawa regime with a centralised imperial government determined to modernise and industrialise.

Perry’s arrival, a step in a wider process, forced Japan to confront its isolation and triggered a dramatic transformation of its political, economic, and military systems.

His mission achieved more than immediate American objectives. It helped to end centuries of Japanese seclusion and initiated a new era in the country's history.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.