Why did the ancient Olmecs carve colossal heads out of stone?

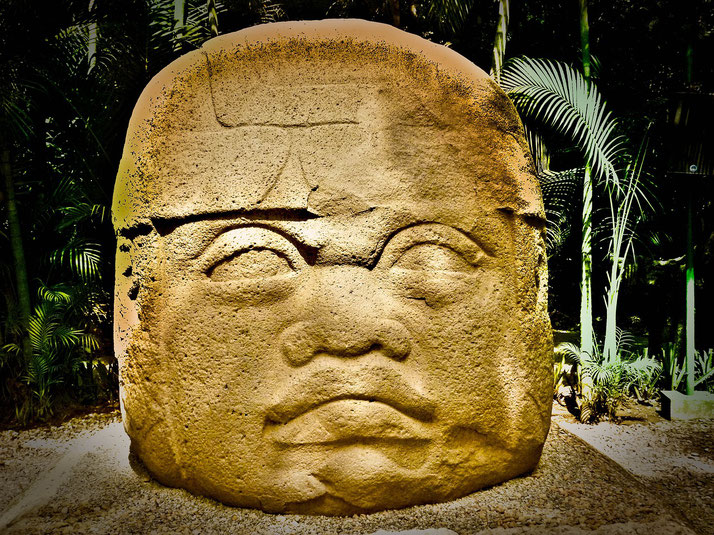

The colossal stone heads of the Olmec civilisation count among the most impressive artefacts from ancient Mesoamerica.

They were carved from volcanic basalt and discovered in ceremonial centres across the Gulf Coast by a society that valued visual displays of power and status.

Archaeologists have debated their exact purpose, but the evidence points to their role as public symbols of rulership and military strength, designed to show authority and keep the memory of top leaders alive.

Who were the Olmec?

The Olmec civilisation appeared in the tropical lowlands of what is now Veracruz and Tabasco around 1400 BCE, and flourished for nearly a thousand years while establishing some of the earliest known urban centres in the region, including San Lorenzo, La Venta, and Tres Zapotes.

These cities contained ceremonial complexes, pyramidal structures and large-scale public artworks.

Olmec society organised itself around a centralised elite class, which controlled trade, oversaw religious rituals and directed those large-scale building projects.

Long-distance trade networks brought valuable materials such as jade, obsidian and iron ore into Olmec territory, allowing artisans to produce high-status goods that strengthened elite control.

The proximity of these cities to river routes also enhanced trade and transportation, while reinforcing the spiritual importance of water in Olmec cosmology.

The Olmecs may have developed early symbolic systems or early symbols, though there is no scholarly consensus on whether these formed a complete writing system.

They constructed ritual ballcourts and likely developed a sacred calendar system that influenced later Mesoamerican civilisations.

Also, their religious beliefs involved powerful deities and mixed creatures, including jaguar-human beings that may have represented royal or spiritual change, which often appeared in their stone carvings.

When were the colossal Olmec heads discovered?

The first documented discovery of an Olmec head occurred in 1862, when José María Melgar y Serrano reported a large stone sculpture at Tres Zapotes.

His observations appeared in a scientific journal, though they failed to spark major archaeological interest at the time.

Serious investigation into Olmec culture did not begin until the twentieth century.

In the 1930s, Matthew Stirling led several expeditions to the Gulf Coast with support from the Smithsonian Institution and the National Geographic Society.

His teams explored San Lorenzo and La Venta, where they uncovered multiple colossal heads alongside platforms, altars, and buried caches of jade.

Stirling’s findings helped establish the Olmecs as a foundational Mesoamerican civilisation and challenged earlier assumptions about the origins of developed society in the Americas.

Archaeologists continued to discover new heads throughout the twentieth century, particularly at sites near ancient river systems.

To date, researchers have identified seventeen colossal heads. San Lorenzo yielded ten, La Venta four, Tres Zapotes two, and Rancho la Cobata one.

These figures remain the most widely accepted as of current scholarship, though individual classifications and counts may vary slightly.

Each site provided new insight into the ceremonial significance and political functions of these massive sculptures.

However, evidence of unfinished sculptures and basalt fragments near quarry sites suggests that some carving may have begun before transport.

What are the stone heads?

Olmec stone heads are carved from single blocks of basalt and range in height from 1.5 to over 3 metres.

The largest examples weigh over 50 tonnes. Every head portrays a human face with distinct features, including wide noses, thick lips, and helmet-like headgear that varies in decoration and style.

These visual details suggest that the heads represented specific individuals rather than generalised figures.

Although none bear inscriptions, some scholars have speculated that they may depict important historical figures, though such identifications remain hypothetical and unconfirmed.

Many of these heads display facial features with realistic asymmetries and expressions.

In particular, the headdresses likely held symbolic meaning, possibly denoting rank, ritual status, or regional identity, while ornamentation such as earspools or carved bands reinforces the impression of elite status and ceremonial authority.

Such artistic details established a visual language that influenced later Mesoamerican portraiture, including the royal stelae of the Maya.

Interestingly, the heads were often placed in important public or ceremonial spaces.

Some stood in plazas, while others were positioned near altars or pyramidal structures.

In several cases, the heads had been deliberately buried or broken, possibly as part of a ritual closure or to indicate political change.

How were the Olmec heads made?

The basalt used to carve the colossal heads came from the Sierra de los Tuxtlas mountains, likely including quarries on the volcanic slopes of Cerro Cintepec.

However, recent studies suggest that multiple basalt sources within the range may have been used.

This mountain region was more than 80 kilometres from the urban centres where the heads were eventually displayed.

Olmec workers quarried the stone using stone tools and natural fissures, and they then transported the rough boulders across great distances, without the use of the wheel or pack animals.

To move these heavy stones, labourers likely used wooden sleds, log rollers, and river rafts, particularly during the rainy season when water levels were high.

River systems such as the Coatzacoalcos and its tributaries provided easy transport routes.

After they reached their destination, workers used tools made of harder materials including obsidian and flint to shape the boulders.

There is also evidence that water and heat may have been used to fracture the basalt before sculpting began.

Artisans first formed the general shape, before they refined the facial features, headdress and surface details.

The sculptors likely worked under elite patronage and followed specific artistic conventions to maintain the recognisability and status of the individuals they depicted.

The finished heads were then installed on prepared platforms or directly in the ground, where they became part of the sacred and political geography of the site.

Why were they made?

The colossal heads were most likely political and ceremonial monuments, carved to honour powerful individuals who held authority over cities and their surrounding regions.

Their scale, public locations, and detailed decorations suggest they were portraits that might have avoided simply memorialising the dead and, instead, probably affirmed dynastic continuity by visually linked the living ruler to divine authority.

The size of the heads ensured visibility in public spaces, where they could command attention and reinforce the ruler’s presence during ceremonies and processions.

The effort to carve, move and set up these heads also showed elite control over labour and resources, since only individuals at the top of the social hierarchy could organise the workforce needed to create such monuments.

As a result, the distinct facial features of the heads also helped to immortalise specific features, allowing future generations to visually identify and honour past leaders.

Their influence on later Mesoamerican cultures

Later Mesoamerican civilisations inherited many aspects of Olmec monumental art and political symbolism.

The tradition of commemorating rulers with stone sculptures continued in Maya, Zapotec, and Aztec societies.

Unlike the Olmecs, these later cultures developed more advanced writing systems, allowing them to add names, dates, and historical events to their stone monuments.

However, the core idea of immortalising elite figures in stone likely originated with the Olmec heads.

Later cultures also adopted Olmec religious iconography and urban planning, particularly by incorporating ritual architectural practices that originated with the Olmecs.

The use of pyramid-temple complexes, the importance of ritual ballcourts, and the practice of burying ceremonial offerings beneath major structures all have origins in Olmec religious practice.

In fact, these cultural traits lasted for more than two thousand years.

Unfortunately, the Olmec did not leave behind written records of their beliefs or history, and yet their visual culture influenced how later civilisations conceived of power, authority and divine kingship.

Regardless, even without inscriptions, the giant heads clearly influenced the vocabulary of political art throughout the region.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.