Why did the Catholic Church declare a ban on crossbows in the Middle Ages?

Developments on the battlefield during the late twelfth century saw a new mechanical weapon that could pierce knightly armour with surprising ease.

As a result, Church leaders faced a difficult choice: how to uphold the ideals of Christian charity, when confronted with a tool whose deadliness threatened both nobles and foot soldiers alike.

In response, a council of bishops issued an official ban. But, did anyone actually take notice fo what they said?

Why was the crossbow so controversial?

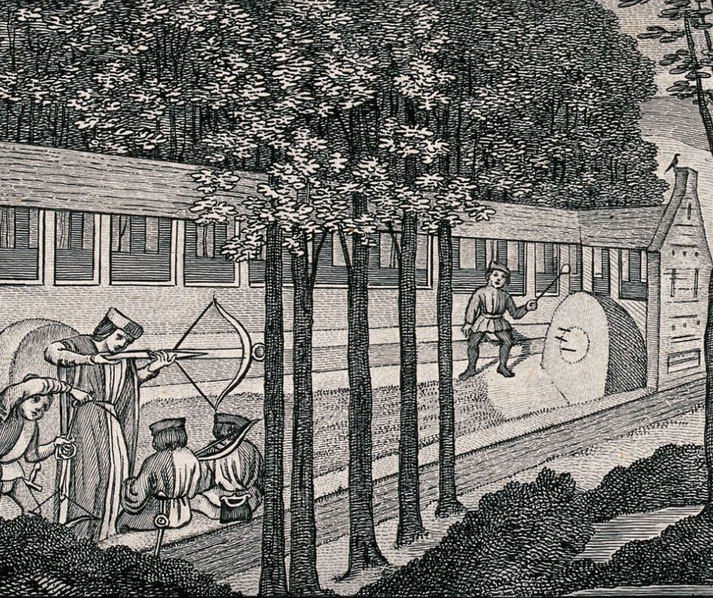

By the twelfth century, the crossbow had gained a reputation as a weapon that upset the social order of warfare in medieval Europe.

Unlike the longbow, which required years of training and physical strength, the crossbow could be mastered quickly by common soldiers.

Its mechanical design allowed a bolt to pierce chainmail and plate armour at close range, removing the protective advantage of mounted knights.

Some models in later centuries reached draw weights of over 1,000 pounds, but during the twelfth century, most military crossbows had much lower draw weights, typically ranging from 300 to 600 pounds.

The idea that a peasant could kill a nobleman from a distance with minimal training worried the warrior elite, who viewed this weapon as a challenge to their military and social superiority.

Among knights and nobles, military status was closely tied to personal combat and acts of bravery that took place on the battlefield.

The crossbow undermined this tradition by enabling unknown and detached killing.

It reduced the value of knightly skill and honour, as it allowed infantry to avoid close combat.

Because of this, many aristocrats began to consider the weapon unchivalrous and cowardly.

Writers expressed moral disgust at the cruelty of wounds caused by bolts that shattered bone and tore through flesh.

Its use contributed to an increasing feeling that the traditional ideals of warfare were under threat, especially when knights began to fall in large numbers to common soldiers who were armed with crossbows.

What role did the Catholic Church play in warfare?

In medieval Europe, the Catholic Church did not remain detached from military matters.

It held great influence over warfare through its ability to bless or condemn armed conflict.

It gave spiritual rewards, such as indulgences, to those who fought in campaigns it supported, such as crusades or defensive wars against pagan or heretical forces.

Clergy regularly preached the moral purpose of such wars, which helped to frame military action as a form of religious duty.

Church authorities also arranged truces and made orders that attempted to limit the conduct of war, especially violence against clergy, peasants, and non-combatants.

Because the Church encouraged the idea of a "just war," the Church sought to regulate violence in Christendom.

Bishops often acted as peacekeepers and even led troops when political necessity demanded it.

At the same time, however, Church councils periodically tried to limit certain forms of violence, especially those that broke the social and religious order.

These efforts reflected the Church's concern for both spiritual discipline and public stability.

As weapons like the crossbow threatened the bases of feudal hierarchy and Christian values of honourable combat, they came under close attention from Church leaders.

Theologians such as Bernard of Clairvaux warned against the spiritual danger posed by random killing, which reinforced the Church's mistrust of such weapons.

Pope Innocent II and the Second Lateran Council (1139)

During the papacy of Innocent II, the Church called the Second Lateran Council in 1139 to address a wide range of issues that the Christian world faced.

Among these was the question of military conduct. Canon 29 of the council banned the use of crossbows and bows against Christians. The decree, which used the phrase "that deadly art... against Christians and Catholics," stated that those who used such weapons in wars between Christians were to be condemned.

This decision emerged in a period of frequent internal conflicts in Europe, where rival factions of nobles and kings regularly fought one another in battles that often drew in Church interests.

Innocent II viewed the spread of the crossbow as a symptom of the growing brutality of warfare within Christendom.

The decision to single it out for prohibition suggests that Church leaders feared its upsetting effect on Christian society.

However, the council banned crossbows only in conflicts between Christians, and limited their use to those wars.

This wording left open the possibility of using such weapons against non-Christians, which would later influence the conduct of crusading armies.

Indeed, in civil wars such as those within the Holy Roman Empire in the twelfth century, the weapon's use worsened church concerns about Christians killing Christians.

What were the reasons for the crossbow ban?

Church leaders believed that crossbows undermined Christian morality; they feared threats to social hierarchy and the erosion of established rules of military conduct.

The Church feared that crossbows permitted killing that showed neither skill nor mercy and that violated the codes of honour upheld by knights.

Because the crossbow enabled foot soldiers to slay knights who had been raised and trained for war, it upset the structure of medieval warfare.

Such a shift threatened to erode the power of the aristocracy and destabilise the political order.

The Church, which relied on cooperation with noble families, had a strong interest in maintaining that order.

There were also religious objections to the cruelty of the wounds caused by crossbow bolts.

These bolts often shattered bone and tore through armour in a way that shocked chroniclers and clergy alike.

In an age when personal salvation and sin were linked to earthly conduct, the use of such a weapon raised serious moral concerns.

New devices such as the windlass and cranequin made crossbows easier to reload and more accessible to common soldiers, increasing the weapon's threat to the ideals of honourable combat.

The ban was part of a wider effort by the Church to limit too much bloodshed in Christian conflicts and encourage warfare that conformed to religious ideals of just conduct and mercy.

Why were crossbows still used despite the ban?

In practice, the ban on crossbows was difficult to enforce. Kings, princes, and military commanders continued to use them in their armies because of their power.

They could be produced at lower cost than training longbowmen and required less time to master.

Mercenary companies, urban militias, and castle garrisons all adopted crossbows for both offence and defence.

Their use spread through cities and territories where papal authority was limited or where the practical demands of warfare outweighed religious instruction.

Furthermore, the ban did not carry automatic punishments such as excommunication or banning church services, so it lacked strong mechanisms of enforcement.

It was issued as part of canon law, but enforcement relied on local bishops and rulers, many of whom had little incentive to restrict access to a powerful weapon.

Emperor Frederick II, who valued military science and innovation, actively employed crossbowmen in his campaigns, which showed how non-church rulers often ignored church restrictions.

Over time, military need won out and crossbows stayed common on the battlefield.

As technology advanced, they became more accurate and easier to reload, which made them even more attractive to commanders who needed dependable long-range attacks in siege warfare and open battles.

The Crusades: A loophole for the crossbow?

During the Crusades, the Church made an exception to its own order. Since the ban only applied to wars between Christians, crusading armies used crossbows freely against Muslim forces in the Levant and North Africa.

While papal bulls did not clearly promote the use of crossbows, they placed no restriction on them and allowed crusader commanders to use whatever weapons they deemed necessary.

Crossbowmen were highly valued in these campaigns. These troops took part in siege operations, defended castles, and played a key role in battles like the Siege of Acre 1189 to 1191, where their ability to target defenders on the walls gave the crusaders an advantage.

The limited enforcement of the ban revealed its true purpose. When the Church allowed its use in crusading warfare, the Church turned the crossbow from a banned tool into a weapon of holy war.

This conflict shows the tension between the Church’s religious beliefs and its willingness to accept military practical needs when it aligned with its interests.

Instead of removing the crossbow, the ban encouraged its spread in conflicts outside Europe.

In the East, crossbowmen became a common feature of crusader armies, although they were never as many as spearmen or as important as mounted knights.

So, did the papal ban on crossbows really matter?

Although the ban on crossbows was notable, it had little effect on the real outcome of medieval warfare.

Armies across Europe continued to deploy crossbowmen in growing numbers, especially in urban militias and mercenary groups.

The Church’s attempt to control new military developments could not keep up with change on the battlefield.

As political and military realities changed, the ban came to be seen as old-fashioned.

By the fourteenth century, crossbows were an accepted part of most European armies, particularly in southern and central regions, even if some kingdoms, such as England, continued to favour longbowmen.

However, the ban did express the Church’s broader concerns about the morality of warfare and the keeping of social hierarchy.

It revealed that the Church used religious authority and social norms to influence military conduct.

Even though the real effect of the decree was minimal, it contributed to a larger conversation about the ethics of warfare in Christian Europe.

The tension between spiritual ideals and military necessity remained unresolved throughout the Middle Ages.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.