The caravel: Revolutionary ship design that opened the world's oceans

During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, European sailors launched expeditions that expanded knowledge of geography and brought previously unknown regions into contact for the first time.

To achieve this, though, explorers needed ships that could travel great distances while also navigating coasts and rivers.

As a result, a new ship design was developed in Portugal in the early 1400s that combined a light structure with a flexible rigging setup, which allowed sailors to adapt to changing conditions at sea and to undertake journeys that larger, heavier ships could not achieve as effectively.

The unique design of caravels

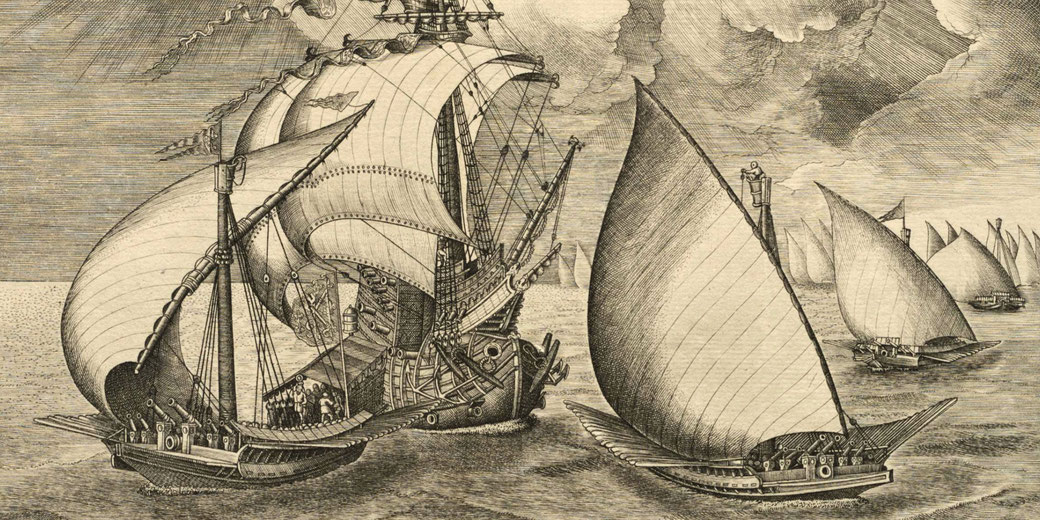

The new ship was known as a 'caravel', which were designed primarily for speed and durability.

Most early examples of these measured between 12 and 18 metres in length and generally weighed between 40 and 60 tons, although some later versions approached 80 to 100 tons.

Their relatively small size meant they could sail in shallow waters yet remain strong enough to endure lengthy ocean crossings.

What is more, their narrow hulls and shallow drafts allowed crews to explore coastlines, enter river mouths, and approach bays where larger vessels risked running aground.

Portuguese shipwrights refined the design in the early fifteenth century to meet the demands of Atlantic exploration, particularly around the Azores, Madeira, and the West African coast, where flexible, easy-to-steer ships were essential.

The rigging of caravels provided sailors with options that could be adapted to changing wind conditions.

Many vessels carried lateen sails, which were triangular sails mounted on angled yards that drew inspiration from Arab dhow designs.

This allowed them to tack more effectively into the wind. Others employed a hybrid arrangement of both lateen and square sails, which gave them the speed of square rigs on open waters and the handling advantages of lateen rigs near shorelines.

Because expeditions often faced unpredictable conditions on uncharted routes, such flexibility proved invaluable.

In addition, the wooden plans were built to create a smooth hull, which mean that it had far more efficient movement through the water and could achieve comparatively high speeds for their size.

Early caravels usually carried around twenty men, and crews rarely exceeded thirty, which made them cheaper to run and easier to supply on long voyages.

Their limited cargo capacity restricted their use in large-scale trade during the earliest stages of exploration, so their purpose centred on scouting and navigation rather than the transport of goods.

Finally, portuguese shipbuilders made sure that this kind of vessel could be built quickly, could be maintained with relative ease, and could be sailed effectively with a small crew.

Caravels in the Age of Discovery

As Portuguese mariners pushed further down the African coast, caravels became the preferred ships for expeditions.

For example, in 1434, Gil Eanes sailed past Cape Bojador using a caravel, which achieved a milestone that many earlier sailors had considered impossible because of strong currents and treacherous winds.

In particular, Prince Henry the Navigator strongly supported the use of caravels for these missions.

During the following decades, navigators such as Nuno Tristão and Diogo Cão relied on caravels to establish contact with African communities in order to expand Portugal’s influence along the coast.

The ship’s reputation increased as it became central to some of the most famous voyages of exploration.

Christopher Columbus sailed across the Atlantic in 1492 with two caravels, the Niña and the Pinta, which accompanied the larger Santa María.

The Niña had originally been a lateen-rigged caravel before being refitted with square sails for the ocean crossing.

The Pinta, a square-rigged caravela redonda of about sixty tons with a crew of roughly twenty-six men, was considered to be well suited to such a voyage.

Their speed allowed them to scout ahead and make course corrections as the fleet entered unfamiliar waters.

Portuguese explorers Bartolomeu Dias and Vasco da Gama both used caravels at crucial stages of their journeys as well.

Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1488 and relied on caravels for their handling in stormy seas, whiel da Gama’s 1497 voyage to India included the caravels São Gabriel and São Rafael.

Why caravels became so crucial to global trade

As sea routes became established and trading posts grew in importance, caravels remained valuable for maintaining local trade networks.

Their ability to sail in shallow waters made them practical for transporting goods between small ports and larger ships anchored offshore.

Portuguese merchants occasionally used them in the Indian Ocean to carry spices such as pepper and cinnamon, as well as textiles and other goods, to larger carracks that completed the journey back to Europe.

Along the African coast, they transported gold dust, ivory, and enslaved people to ships engaged in the expanding Atlantic trade, which acted as a useful link between inland regions and transoceanic transport.

Caravels were instrumental in supplying trading posts like Elmina, founded in 1482, and Mozambique Island, which became a key staging point in 1498.

Because caravels were relatively inexpensive to build and required fewer crew members than larger ships, they became a common feature in fleets that supported the growth of European empires.

Spanish traders in the Caribbean used them extensively to move supplies between settlements and to transfer goods to treasure convoys bound for Europe.

Specifically, their speed and manoeuvrability also made them valuable for communication and for evading pirates, who increasingly targeted vulnerable trade routes.

Even after new ship designs gradually replaced them for long-haul voyages, caravels continued to serve in regional trade and exploration well into the seventeenth century.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.