What was the ancient warrior philosophy of Bushido?

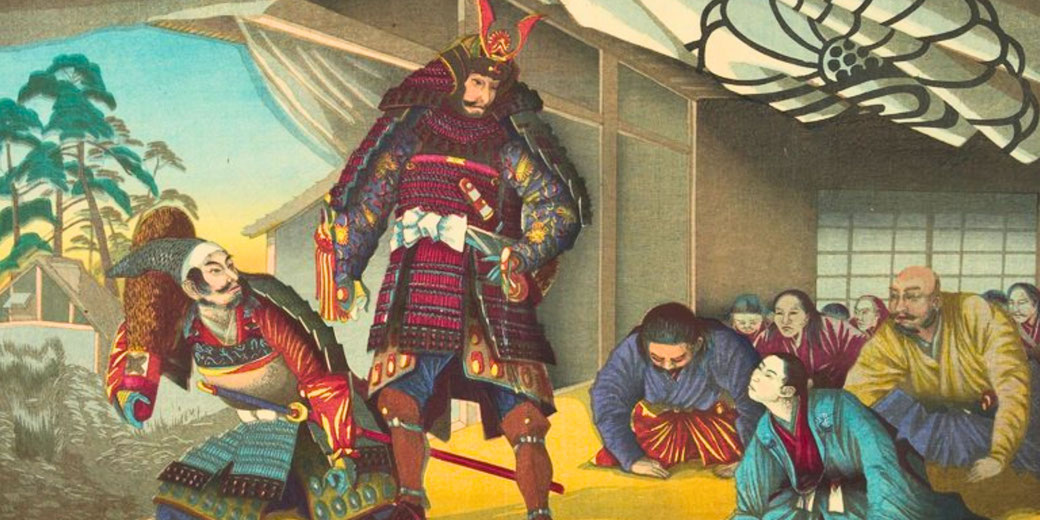

On the battlefield, where life and death were decided in moments, Japanese warriors followed a code that demanded absolute loyalty and unshakable courage.

Over time, its principles even transcended war, which set the standards of behaviour of an entire social class.

The historical development of Bushido

Bushido developed in Japan as a moral code that guided the conduct of the samurai class, and it became central to their identity as leading warriors.

The term meant “the way of the warrior,” and it described a set of ethical principles that directed how samurai should live, fight, and die.

Early moral ideals associated with loyalty and duty developed among warrior bands known as bushidan in the late Heian period, and the Genpei War between 1180 and 1185.

The word bushidō itself first appeared in written sources during the early Edo period, when scholars and chroniclers codified the expectations of the warrior class.

Samurai who followed Bushido were expected to value personal honour above life itself, and ritual suicide through seppuku was regarded as preferable to disgrace.

Minamoto no Yorimasa’s celebrated seppuku in 1180 became one of the earliest famous examples of this act, even though some accounts suggest that Minamoto no Tametomo performed such a death slightly earlier.

The philosophy gradually developed through the Kamakura and Muromachi periods before receiving formal codification in the Edo period.

What were the central principles of Bushido?

Bushido emphasised loyalty to one’s lord as an absolute duty, and samurai were bound by a strict sense of obligation to the daimyo who granted them position and livelihood.

Honour remained the central virtue that governed a samurai’s behaviour both on and off the battlefield.

Courage was understood as moral bravery that required self-control rather than reckless violence, and the ideal samurai showed calm determination in moments of danger.

Self-discipline and composure under pressure were also admired as qualities that revealed inner strength.

Finally, benevolence and righteousness were also regarded as essential virtues, and a samurai who abused power or inflicted cruelty risked dishonour and disgrace.

The philosophy of Bushido incorporated more than warrior values because a complete samurai education required intellectual and artistic training.

Instruction in literature, poetry, and calligraphy was also considered important, and young samurai were encouraged to master cultural accomplishments alongside swordsmanship.

Arts such as the tea ceremony, Noh theatre, and ink painting formed part of their training too.

Figures like Hosokawa Yūsai, who was both a warrior and a noted poet, illustrated the expectation that a samurai should develop refined cultural skills.

Confucian ideals reinforced respect for social order and filial piety, and Buddhist teachings on impermanence and detachment were thought to help reduce the fear of death.

How Bushido changed after the fall of the samurai

By the Edo period, which lasted from 1603 to 1868, Japan experienced a time of relative peace under the Tokugawa shogunate, and samurai had fewer opportunities for battle.

Many took on administrative and bureaucratic roles that required education and moral discipline rather than military service.

Bushido persisted as an ethical ideal, and scholars wrote extensively about the virtues that defined a true warrior.

Yamaga Sokō, who lived from 1622 to 1685, and Yamamoto Tsunetomo, who lived from 1659 to 1719, were among the most influential thinkers of the time.

Tsunetomo’s Hagakure, composed in the early eighteenth century, outlined the standards of conduct that samurai should uphold and famously stated that “the way of the warrior is found in death,” which expressed the belief that loyalty and honour demanded constant readiness to sacrifice one’s life.

Daidōji Yūzan’s Budō Shoshinshū of 1716 also provided practical moral advice for young samurai.

Samurai who no longer fought in wars still regarded themselves as guardians of moral order, and Bushido provided a code of behaviour that preserved their prestige and purpose.

The influence of Bushido expanded as Japan modernised in the late nineteenth century during the Meiji Restoration, and nationalist leaders promoted it to encourage loyalty to the emperor and the state.

Nitobe Inazô’s 1899 book Bushido: The Soul of Japan introduced the concept to Western audiences and helped popularise it internationally.

Military leaders used the code to inspire soldiers to fight bravely and accept death as a duty to the nation.

Ideas of self-sacrifice and unwavering loyalty also influenced Japan’s military spirit in the early twentieth century, and Bushido influenced the conduct of Japanese forces in conflicts such as the Russo-Japanese War of 1904 to 1905 and World War II, which included the kamikaze missions.

Modern Japan treats Bushido with respect and caution because it was adapted to support militarism in the twentieth century.

The philosophy continues to feature in martial arts training and public discourse on ethics, and it remains a prominent cultural reference in literature and in film and in education.

In fact, Akira Kurosawa’s samurai films and modern martial arts such as kendo and judo continue to use Bushido as the moral framework that once defined Japan’s warrior class.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.