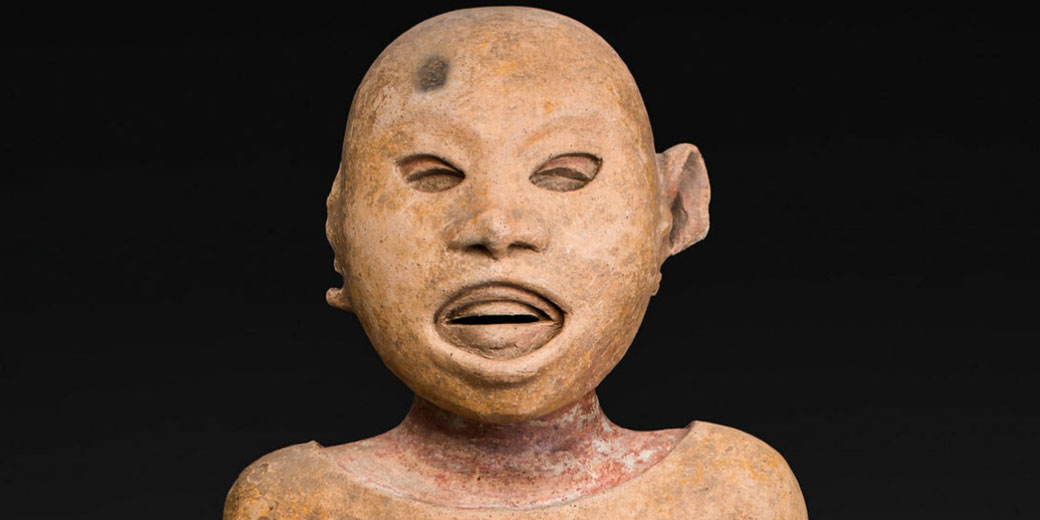

Silent killer of the Aztecs: The gruesome epidemic that toppled an empire

When Hernán Cortés and his Spanish expedition arrived on the Gulf coast of Mexico in 1519, unknowingly introduced foreign pathogens into a densely populated region where millions of Indigenous people had no inherited resistance to Old World diseases.

Among the deadliest of these invaders was smallpox, a viral infection that swept through Mesoamerican communities with terrifying speed and extreme deadliness.

Within two years of contact, this invisible agent dismantled the structure of Aztec society and helped bring one of the Americas’ most powerful empires to its end.

Contact with Europeans

Spanish ships landed near the town of Veracruz in the spring of 1519, and the men who disembarked soon began their march toward the interior.

Cortés led a small force of around six hundred Spaniards, but he increased his strength through alliances that he formed with Indigenous groups such as the Totonacs and Tlaxcalans, who had long resented Aztec control.

After months of negotiations and skirmishes backed by calculated diplomacy, he advanced into the Valley of Mexico and arrived at the gates of Tenochtitlán in November.

The Spaniards entered the capital as guests of Emperor Montezuma II, who received them with gifts, formal greetings, and careful adherence to protocol.

However tensions grew in the following months as the visitors began to intervene in the city’s affairs.

Some accounts suggest that smallpox may have entered the empire with a member of the Spanish party who had contracted the disease during the transatlantic voyage, possibly from the later expedition led by Pánfilo de Narváez, but the exact source remains uncertain.

When he entered the densely inhabited centre of the empire, the virus began to take root in an environment where the population lacked prior exposure and immunity to such infections.

The first symptoms may have gone unnoticed, but the outbreak soon sped up.

The Outbreak

Spanish forces temporarily withdrew from Tenochtitlán in mid-1520 to confront a rival expedition dispatched from Cuba.

During their absence, the garrison left behind in the city sparked an uprising after massacring Indigenous elites during a sacred festival.

As open warfare broke out between the Spaniards and the Aztecs, smallpox began to spread rapidly through the capital.

It infected both warriors and civilians and cut through every class and occupation without regard for age or rank.

Accounts from the period describe the disease with graphic detail. Victims developed high fevers, severe headaches, and skin eruptions that soon turned into deep, oozing sores.

The blisters clustered around the face, hands, chest, and back, eventually covering the entire body.

Many patients were unable to move because of pain and could not stand or eat. In the most severe cases, the infection led to pneumonia or organ failure, and those who perished were often left unburied for days.

Indigenous chroniclers later wrote that people “died in heaps, like bedbugs,” and survivors sometimes had no strength to bury the dead.

The rate of transmission increased as infected individuals wandered the city in a confused state or were hidden by family members who did not understand the risk of exposure.

From the heart of Tenochtitlán, the virus moved outward along trade routes, river paths, and pilgrimage roads.

Merchants, refugees, and messengers unknowingly became carriers, and by the time authorities attempted to contain the disease, it had already reached neighbouring towns and distant provinces.

Over the following decade, it spread south into the Maya region and eventually reached Guatemala, where it caused additional outbreaks.

Impact on the Aztec Population

The population decline that followed the introduction of smallpox is among the worst in recorded history.

In some regions, the death rate exceeded fifty percent within a single year. Entire families vanished.

In rural areas, entire villages fell silent. Fields went untended, aqueducts broke down, and the social systems that had sustained the empire began to falter under the weight of so much loss.

Historians estimate that the Valley of Mexico may have held 15 to 20 million people before contact, yet within a century the population fell to somewhere between two and three million, according to most estimates.

The death of Emperor Cuitláhuac, who had succeeded Montezuma II following the initial revolt, added political chaos to the physical devastation.

His reign lasted only a few months before the disease took him, leaving the throne vacant once again.

The power vacuum destabilised the capital and interrupted plans to reorganise the military defence of the city.

Senior warriors, local governors, tax collectors, and engineers died in such numbers that effective government became impossible.

The succession problem made Cuauhtémoc emperor, but he inherited a capital already crippled by loss.

The empire’s tribute system collapsed as surviving provinces failed to send food, labour, or textiles to Tenochtitlán.

Markets closed due to both fear of infection and the loss of skilled traders. Priests found it difficult to carry out major ceremonies as musicians, dancers, and acolytes fell ill.

Famine took hold in some districts as transportation halted and storehouses emptied.

Spiritual confusion increased as the gods appeared either silent or angry. Some believed that Tezcatlipoca had sent the plague as punishment, while others feared the gods had abandoned them entirely.

People searched for explanations in omens, prophecies, and ritual sacrifice, but the epidemic continued to spread without pause.

How the Aztec Responded and Measures Taken

Medical specialists within Aztec society had centuries of knowledge in herbal treatment, surgical techniques, and overall health practices.

However, smallpox presented symptoms they had never encountered, and most remedies proved useless.

Physicians attempted to cool the fever using mud poultices, herbal steam baths, and infusions made from plants like sage, epazote, and marigold, but the infection often progressed beyond their ability to manage it.

Priests called for acts of repentance and intensified the frequency of offerings at temples dedicated to disease-related deities such as Tezcatlipoca and Tlaloc.

Special sacrifices were made, and new chants were composed to restore religious balance.

Yet these efforts failed to prevent the suffering, and the emotional toll deepened when priests themselves fell ill.

Without religious guidance, many people began to question the strength of their gods and the reliability of their religious leaders.

Government officials ordered that the sick be isolated in their homes or removed to specific districts, but overcrowding made enforcement difficult.

In many areas, family members refused to abandon the dying and remained in contact long after symptoms appeared.

Efforts to contain the disease broke down, and new waves of infection swept through the remaining population.

Refugees from the capital spread the virus into distant mountain valleys and coastal plains, and local communities had no time to prepare or respond.

In desperation, some towns closed their borders and turned away travellers.

Others sent emissaries to neighbouring cities in search of medicine, advice, or assistance, but they often returned too late to help those already stricken.

Smallpox created such widespread fear that it changed patterns of migration, trade, and religious practice across Mesoamerica.

Collapse of the Aztec Empire

When Cortés returned to the Valley of Mexico in 1521, he did not face the same powerful resistance he had encountered the year before.

His new army included thousands of Indigenous allies who had suffered under Aztec tribute demands, and many of them had already lost relatives to the epidemic.

The Spanish encountered a capital city weakened by disease, discouraged by leadership losses, and weakened by hunger.

Cortés himself acknowledged that “a great number of the Indians died… most of smallpox,” and Spanish soldiers noticed that they suffered far less because many had already carried immunity from childhood exposure in Europe.

The final siege of Tenochtitlán began in May and continued for nearly three months.

The defenders fought with courage and determination, but their ranks had thinned dramatically, and supplies had dwindled.

The once-bustling island city was surrounded by canals and was protected by causeways.

It became a ruin of corpses, collapsed buildings, and polluted water. By August, Cortés and his allies forced their way into the heart of the city.

On 13 August 1521, the last emperor, Cuauhtémoc, surrendered after being captured while trying to flee.

Following the conquest, Spanish chroniclers praised their own tactics and weaponry but knew that smallpox had done more to defeat the Aztecs than any musket or cavalry charge.

The disease killed leaders, destroyed social unity and took away the empire’s ability to recover.

What the sword began, the virus completed, and it meant that a civilisation that had ruled for centuries fell within two years of contact.

An epidemic that left millions dead before most battles had even begun caused the empire’s fall rather than European military power.

Recurring epidemics of smallpox, measles, and typhus in the decades that followed prevented demographic recovery and ensured that Spanish colonisation advanced over a land whose population had been drastically reduced by repeated epidemics.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.