Sacred rituals and bloody ceremonies: Unmasking the true role of Aztec Priests

In Aztec society, their priests were in a powerful position within a civilisation that placed religion above almost all other concerns.

They were responsible for directing the rituals that were thought to sustain divine power, which often involved human sacrifices that ensured the continuation of the cosmos.

What was daily life like for the people in these roles?

The central role of religious belief in Aztec society

Aztec civilisation depended on a religious understanding of the universe that explained the world’s origins, its continued existence, and the responsibility of humans within it.

People believed that the gods had sacrificed themselves to create the Fifth Sun, the present age, and that life could only continue if humans returned the gift through constant offerings of blood and life.

As a result, their religion explained natural events, justified conquest, and guided social behaviour.

Victories in battle demanded public sacrifices, while droughts called for prayers to Tlaloc, the god of rain.

Women in childbirth received ritual protection from priestesses, and merchants consulted calendars before departing on long journeys.

Priests supervised every element of these ceremonies, making sure that each ritual followed the correct form and met divine expectations.

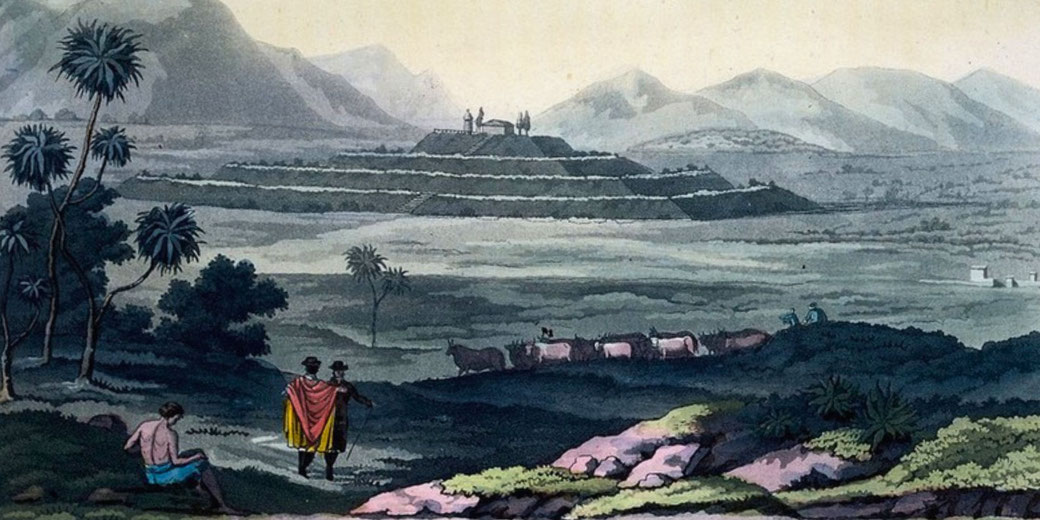

The city of Tenochtitlan alone featured numerous ceremonial structures, with some colonial records referencing up to seventy-eight buildings used for religious or administrative purposes across the empire.

During major festivals, hundreds of priests took part in rituals that lasted for days.

Priests also controlled knowledge of time. The sacred calendar, known as the tonalpohualli, and the solar calendar, the xiuhpohualli, created overlapping cycles that determined every festival, agricultural task, and military expedition.

Each day had its own patron deity and spiritual significance. The tonalpohualli, with its 260-day cycle formed by the interaction of twenty day signs and thirteen numbers, reflected a cosmology linked to the thirteen heavens and nine underworlds.

Priests interpreted these meanings for rulers, warriors, and commoners in order to reinforce the religious order and regulated the rhythm of society.

Religious instruction took place in temples and schools. Boys learned myths, chants, and sacred songs, while priests taught astronomy, mathematics, and moral self-control.

These lessons helped preserve cultural traditions and prepared future leaders for lives of service.

Education was seen as a religious duty. Among girls and women, priestesses taught elements of household ritual and the honouring of fertility deities.

The different kinds of Aztec priests

The priesthood followed a rigid hierarchy with distinct offices, each responsible for different rituals and temples.

At the top, a high priest known by titles associated with Quetzalcoatl and referred to in sources as the tlamacazqui supervised the most holy rituals in Tenochtitlan. H

e directed large festivals and advised the emperor on spiritual matters. The high priest of Huitzilopochtli held similar authority in ceremonies linked to war and sun worship, though the specific title 'Huitznahua Teohuatzin' appears to be a modern scholarly construction rather than an attested Nahuatl term.

Regardless, during the Panquetzaliztli festival in the fifteenth month of the solar calendar, this priest led rites that continued for twenty days and culminated in mass sacrifice.

Other priests served more specialised roles. The tlamacazqueh performed daily temple duties, while the cihuatlamacazqueh led rituals dedicated to fertility goddesses and guided women through life-cycle ceremonies.

Each priest followed strict training and performed duties connected to specific gods, temples, or regions.

Certain priests functioned as diviners or seers. For example, the tonalpouhqui interpreted the sacred calendar and chose appropriate days for battle, marriage, or sacrifice.

Others worked as astronomers, keeping track of solar movements and planetary alignments.

Some priests were associated with the abilities of nahualli, individuals believed to possess animal spirit companions or the power to transform spiritually into creatures such as jaguars, owls, or coyotes.

Priests who specialised in particular gods often wore distinct clothes and carried symbolic objects.

Feathers, cloaks, and painted faces served not as decoration but as tools for spiritual communication.

For example, the high priest of Huitzilopochtli wore a hummingbird headdress and a mirror of obsidian on his chest to reflect the solar nature of the god.

During large festivals, these priests acted out mythological dramas and performed as living embodiments of divine forces.

How to become an Aztec priest

Boys who trained for the priesthood were usually born into noble families entered the calmecac, a school attached to temple complexes, though especially talented commoners were occasionally admitted based on merit.

In these institutions, they studied the sacred calendar, learned ritual songs, and memorised myths.

They also trained in public speaking, astronomy, and moral conduct.

The priesthood required personal sacrifice. As such, students fasted, carried burdens, and drew blood from their own bodies as acts of penance.

Older priests supervised their progress and tested their endurance through spiritual trials.

Life expectancy varied depending on the intensity of these self-controls, though those who survived their youth often served into middle age.

Commoner boys usually attended the telpochcalli, which prepared them for military service.

Occasionally, those who showed exceptional spiritual understanding were selected for temple duties.

Although rare, some rose through the ranks and became respected priests.

Admission depended more on devotion and skill than birth alone.

A day in the life of an Aztec priest

Priests began their duties before dawn. After bathing in cold water to purify their bodies, they offered blood to the gods by piercing their ears, tongues, or thighs with sharp thorns.

These offerings sustained divine energy and maintained the balance of the cosmos.

During the day, some priests cleaned temple precincts and prepared food for offerings.

Others burned copal incense or chanted hymns in front of the altars. Senior priests prepared for larger ceremonies, inspected ritual items, and guided younger assistants.

In painted codices such as the Codex Magliabechiano and Codex Mendoza, scenes depict priests engaged in these daily rites.

However, priests also performed civic roles, usch as keeping historical records in painted codices and advised rulers on decisions of war, law, and diplomacy.

At night, many priests slept inside temple grounds, as they observed rules of silence and seclusion.

They avoided comfort and personal enjoyment, because they believed that the gods demanded purity and focus.

Aztec priests and human sacrifice

Because Aztec priests believed that human sacrifice sustained the universe, they thought that the gods had given their lives to create the world, and the only proper repayment came in the form of human blood and hearts.

Priests viewed sacrifice as an expression of devotion. Without it, the sun would fall from the sky and the world would end in darkness.

Victims of sacrifice included war captives, slaves, and chosen individuals raised for ceremonial purposes.

Some priests would impersonated gods during festivals and gave the victims special honours before their deaths.

Priests would then wash and dress them in sacred costumes, then led them in public processions to the top of the temple.

On the temple summit, four assistants held the victim, while the officiating priest used a sharp obsidian blade to cut open the chest and remove the heart.

The heart was then raised toward the sky and placed on a ceremonial plate, while the body was thrown down the temple steps.

Eyewitnesses such as Bernal Díaz del Castillo described the temples as places that reeked of blood and were filled with robed priests who wore long, matted hair and blackened clothing.

Other forms of sacrifice included flaying, drowning, and burning. During the festival of Tlacaxipehualiztli, priests wore the skins of flayed victims as sacred clothes.

In the month of Toxcatl, a young person chosen to represent Tezcatlipoca lived in splendour for a year before his sacrifice to reenactment one of the divine myths.

What happened to the priests when the Spanish arrived?

Spanish conquistadors viewed Aztec religion as a threat to Christian belief and colonial control.

When Hernán Cortés entered Tenochtitlan in 1519, he ordered the destruction of idols and forced the cessation of sacrifices.

Priests who resisted were punished or killed. Temples were looted and burned, and Catholic masses replaced traditional ceremonies.

Surviving priests were captured, executed, or forcibly converted to Christianity.

Some Nahua scribes continued to record traditional knowledge in secret. Spanish friars used their assistance to create codices that preserved parts of Aztec belief.

In remote areas, certain rituals survived in disguised forms. However, the formal priesthood disappeared under colonial rule.

The collapse of the Aztec religious system ended centuries of temple worship, but traces of priestly knowledge remained in oral tradition.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.