The strangest stories of Aztec mythology

Aztec mythology preserved some of the most bizarre stories filled with unsettling events that try to explain the cosmic order, justified religious practice, and described the roles of gods and humans.

Unlike many mythologies that described gods as distant, Aztec gods revealed themselves through terrifying forms, strange transformations, and some truly disturbing rituals.

1. The Five Suns

Aztec cosmology divided time into five successive eras, each ruled by a different sun and brought to an end through disastrous events.

These suns did not refer to celestial bodies in space but to cosmic ages controlled by divine forces that could destroyed them when harmony failed.

The first sun, Nahui Ocelotl or "Four Jaguar," came under the rule of Tezcatlipoca, god of the night sky.

When the people angered the gods, jaguars consumed the human race and ended the era.

Tezcatlipoca lost power after Quetzalcoatl struck him from the sky with a blow to his face, which began a cycle of divine rivalry.

Quetzalcoatl ruled the second age, Nahui Ehecatl or "Four Wind," yet the peace of that time broke apart when fierce hurricanes destroyed the world.

Humans turned into monkeys, and the gods destroyed the era once they saw the result.

Tlaloc, the god of rain and storms, controlled the third sun, Nahui Quiahuitl or "Four Rain."

He grew furious when humans ignored his worship, so he brought down fiery rain from the heavens. Survivors became birds, leaving the world empty again.

The fourth era, Nahui Atl or "Four Water," began under Chalchiuhtlicue, goddess of rivers, who flooded the world when her heart filled with sorrow.

Her grief submerged the earth and forced the transformation of humankind into fish.

Each of these destructions resulted from disobedient mortals and angry gods, which was ment to be a warning to future generations.

The current age, Nahui Ollin or "Four Movement," started only after divine sacrifice.

At Teotihuacan, the gods assembled to choose a new sun. Nanahuatzin, a sickly and humble god, stepped forward and threw himself into a great fire.

Tecuciztecatl, a proud and richly adorned god, followed behind him. Nanahuatzin became the sun, and Tecuciztecatl became the moon.

However, the new sun remained motionless until the other gods offered their own lives to set it in motion.

This helped explained why human sacrifice became necessary in Aztec ritual life.

Without it, the world would once again fall into darkness.

2. The Curious Case of Xolotl

Xolotl, twin brother of Quetzalcoatl, played a strange and contradictory role in Aztec belief.

As the god of lightning, fire, deformity, and death, he guided souls through the dangerous journey of Mictlan, the nine-layered underworld.

He also protected the sun during its nightly descent through darkness, yet his myths focused more on his cowardice, his transformations, and his refusal to fulfil divine duty.

According to one tale, when the gods agreed to sacrifice themselves to start the Fifth Sun, Xolotl panicked and ran.

He did not wish to die, so he hid from the others by changing his form into other things.

First, he became a maize plant, then an agave stalk, and finally an axolotl, a strange aquatic creature that lived in the lakes around Tenochtitlan.

Despite these attempts to evade death, the gods eventually found him and forced his sacrifice.

His story warned that even divine beings could fail their duties.

Xolotl also featured in the myth of humanity's rebirth. He accompanied Quetzalcoatl to Mictlan to retrieve the bones of the dead, which they used to create the new race of humans.

During their escape, he stumbled, and the bones broke. This was meant to explain the unequal size of people and the imperfect nature of humanity.

As a result, he gained a reputation as both helper and hindrance because he aided his twin in restoring life, yet he also caused human flaws.

In Aztec art, Xolotl appeared with backward feet and a canine face, a sign of his link with unnatural forms and deceptive behaviour.

He existed on the boundary between life and death. Where Quetzalcoatl symbolised light and culture, Xolotl stood for shadow and hesitation.

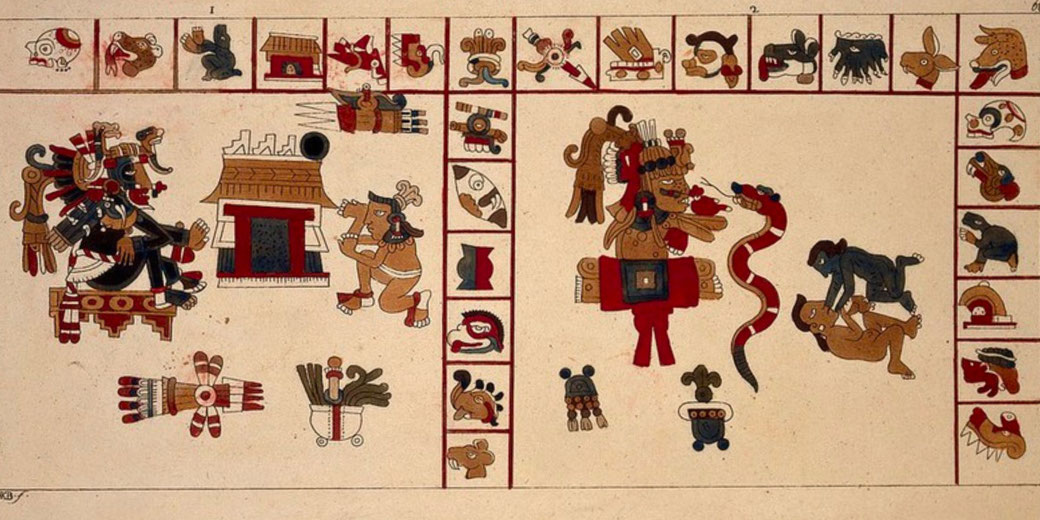

3. Tlazolteotl: The Eater of Filth

Tlazolteotl fulfilled one of the most disturbing yet morally complex roles in the Aztec pantheon.

Known as the goddess of acts of vice, ritual purification, and powers over fertility and disease, she both caused sin and cleansed it.

Her name came from tlazolli, which meant "filth" or "moral corruption." People believed she tempted mortals into wrongdoing, particularly in matters of sexuality, then consumed their sin during confession rituals.

Priests urged people to confess to Tlazolteotl before their death. If they failed, they would carry their guilt into the afterlife and suffer punishment in Mictlan.

Ritual confession allowed her to consume the sin, making her one of the only deities who offered mercy.

This, however, carried disturbing imagery. The "filth" she consumed represented the spiritual waste rather than physical dirt left by immoral behaviour.

People believed that hidden sins caused many physical illnesses, and Tlazolteotl had the power to purge these ailments.

Artists showed her in many forms. Some showed her as a black-faced goddess with fierce expressions and bloodstained garments.

Others described her in a maternal form, connected to childbirth and fertility, since she gave birth to Centeotl, the god of maize.

In some versions of her myth, she worked together with her sisters instead of acting alone, who were called the Ixcuina and each one had power over a stage of female life or a kind of desire.

Among the Spanish writers who recorded the Aztec religion, Tlazolteotl was particularly shocking: a goddess who both corrupted and forgave, she challenged simple divisions between good and evil.

For the Aztecs, her role made sense. Humans sinned because gods created them from broken bones and borrowed blood, and Tlazolteotl existed to clean what could never stay clean for long.

4. The Love and Loss of Mixcoatl and Chimalma

Mixcoatl was a god of hunting and the heavens who featured in many myths as an ancestral figure.

In one of the strangest stories of divine romance, he encountered Chimalma, a mortal woman whose name meant "shield-hand."

When he tried to approach her in the forest, she stood her ground and refused him.

He shot five arrows at her, which she caught with her shield. After that moment, she conceived a child without any physical contact.

The child born from this unusual union grew into Topiltzin Ce Acatl Quetzalcoatl, a culture hero and god of wind and the priesthood.

In some versions of the myth, Mixcoatl died before the child's birth, murdered by his own brothers in a struggle for power.

Chimalma fled and gave birth in secret, so she raised her son in a hidden place where he would be safe from the danger that had killed his father.

Quetzalcoatl later returned to power, led a religious movement, and became a god after being betrayed and exiled.

The original myth, however, focused more on the mystery of his birth story and the grief of his mother.

It stood apart from the violent, ritual-heavy myths of Aztec religion, and it described a story of quiet suffering and private loss, with divine power growing from pain rather than conquest.

The tale of Mixcoatl and Chimalma avoided the sacrifice of captives, the wrath of gods, and cosmic destruction.

Instead, it told of love, rejection, and silent strength. In a mythology filled with fire, blood, and thunder, this story was something stranger: the idea that creation could begin with refusal instead of violence.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.