Zheng He and the Chinese Treasure Fleet: The greatest explorer you've never heard of

There was a moment in history a single fleet of sailing ships carried more people than any other fleet ever did before, and it sail halfway around the world to connect with the world’s most remote lands.

It set up trade networks and formal contacts with foreign governments in one of the most remarkable medieval achievements.

This was the world of Zheng He and the incredible Chinese Treasure Fleet.

Who was Zheng He?

Zheng He (also known as Cheng Ho) was a Chinese explorer and admiral who lived during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).

He is known as one of the most skilled sailors in history because he led a series of voyages that took him to remote lands with the aim of making China the unchallenged naval power of the age.

Zheng He was born with the name Ma He in 1371 in Kunyang in Yunnan province, in south-west China. He came from a Muslim family.

When he was 11, he was captured by the Ming army during a conflict in Yunnan and was later castrated.

He then served at the court of the Yongle Emperor, the third ruler of the Ming Dynasty, where he became a trusted adviser and a skilled sailor.

The creation of the Treasure Fleet

At the time, the Yongle Emperor had a bold plan to attempt to dramatically increase the spread of Chinese influence and trade across the known world.

In particular, he wanted China to be a leading naval power. Zheng He was appointed as admiral and order to launch an expedition to discover new lands and make formal contacts with foreign governments.

He was also tasked to bring back valuable items.

The first expedition launched in 1405 with more than 27,000 men, including sailors, soldiers, interpreters, and a range of government officials.

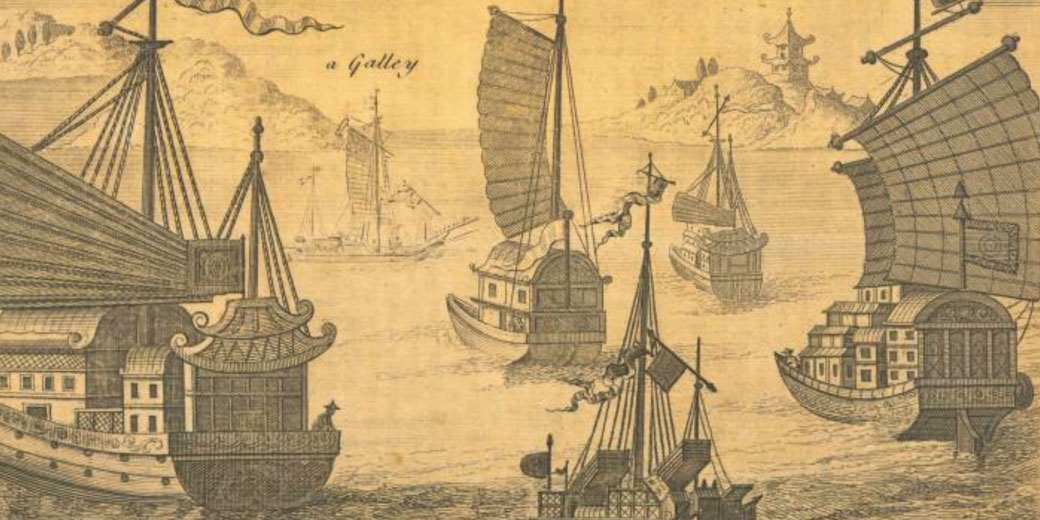

At that time, the fleet had over 300 ships, including 60 large treasure ships. Traditional Ming Chinese records state that these treasure ships were up to 127 metres (417 feet) long and 52 metres (171 feet) wide.

Some modern historians have suggested more conservative estimates of around 70–90 meters (230–295 feet) in length, based on archaeological evidence and the size of medieval Chinese shipyard remains.

Regardless, these were larger than any other vessel at the time, and each one reportedly had nine masts, four decks could carry up to 500 people.

Also, the Treasure Fleet included advanced shipbuilding methods for the time, such as watertight bulkheads, and stern-post rudders, as well as sophisticated navigation equipment, including as magnetic compasses and the best star charts the imperial scholars could provide.

These innovations would not be matched by other civilisations for many years afterwards.

The fleets included dedicated ships to transport horses, fresh water, and enough food for everyone involved.

Zheng He's journeys

In total, Zheng He led seven major voyages between 1405 and 1433, which sailed through the South China Sea, the Straits of Malacca, into the Indian Ocean and the Arabian Sea.

In fact, it is claimed that they travelled as far west as East Africa and the Persian Gulf, and as far east as Indonesia and the Philippines.

The fleet visited over 30 foreign states, stopping at major ports such as Calicut in India, Hormuz in Iran, and Malacca in present-day Malaysia.

On these voyages, Zheng He and his crew brought back foreign goods such as spices, textiles, and precious stones, as well as new plants and animals that were previously unknown in China.

At each stop, Zheng He made a concerted effort to meet with foreign rulers and exchange elaborate diplomatic gifts in returned for lucrative trade deals.

On one voyage, he even brought back a giraffe for the emperor, which was a gift from the Sultan of Malindi (modern-day Kenya).

The purpose of the voyages

Aside from the all-import trade benefits, the main goal of the Treasure Fleet was to show off Ming Dynasty strength.

The visual spectacle of so many large ships appearing on the horizon, and the impressive geographical reach of their expedition was meant to demonstrate China’s ability to extend its influence far from its own shores.

In a way, Zheng He’s voyages were also about celebrating contemporary Chinese culture in a way that awed those he met.

To achieve this, he brought with him Chinese art, books, and technologies to share with the lands he visited.

The end of the Treasure Fleet

Despite its remarkable achievements, the Treasure Fleet was eventually disbanded by the mid-15th century.

Later, historians suggest this happened because of internal political unrest in the Ming dynasty.

There were growing economic pressures and a growing desire for international isolation within later rulers of the Ming court.

Zheng He died at the age of 62 in 1433, during his seventh and final voyage. Most sources say that he died in Calicut (now Kozhikode), India, likely from an illness he contracted on the journey, while the fleet was preparing to return to China.

According to tradition and Muslim custom, he was buried at sea

Sadly, Zheng He’s life and achievements were largely forgotten in China after his death.

It was after this point that the Ming Dynasty turned inward and stopped investing in the expensive naval expeditions.

In fact, in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, Ming officials, especially under Chancellor Liu Daxia, ordered the destruction of many records of Zheng He’s voyages.

It was only in the 20th century that evidence of Zheng He and his journeys were found again and were honoured, both in China and abroad.

A cenotaph tomb was later erected for him on Niushou Hill (Cattle Head Hill) in Nanjing, China, which is believed to contain his clothes and headgear rather than his remains.

However, it seeks to honour his significant role in medieval Chinese maritime history and world exploration.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.