7 of the weirdest and most disgusting jobs you could do in ancient Rome

Ancient Rome had some truly unusual jobs. The city was famous for its emperors and gladiators, but Romans performed tasks both strange and essential...

How to get a job in ancient Rome

In the busy streets of Rome and other major cities, one could find many different professions.

Artisans, traders, and merchants filled the marketplaces and sold everything from exotic spices to detailed jewellery.

Skilled workers like blacksmiths, carpenters, and masons were in high demand, especially for government construction projects.

Meanwhile, the Roman legions offered a different kind of employment, one that promised Roman citizenship upon completion of service.

The legal profession was another path for social mobility, as skilled speakers could rise through the ranks to become influential senators.

Yet, not all jobs were equal. Social standing played a major role in determining the type of work someone could pursue.

The elite often held positions of power and influence, while the lower classes performed more menial, labour-intensive tasks.

Slaves, who were considered property rather than citizens, were often forced into the most difficult and degrading jobs, which illustrates how social status influenced one’s options in ancient Rome.

1. Armpit Plucker (Alipilus)

It's easy to overlook the simpler professions that contributed to the daily life and wellbeing of the population.

One such job, which might surprise us today but was essential in ancient Rome, was that of the Armpit Plucker, or Alipilus.

This profession was part of the broader area of personal grooming, which was surprisingly advanced despite the technological limits of the time.

They were mainly responsible for removing unwanted body hair, especially from the armpits. They used tools such as tweezers and specialised waxes.

While the task might seem unimportant today, it was crucial to Roman beauty standards, which valued smooth, hairless skin as a sign of cleanliness and sophistication.

The role of the Alipilus was not just about looks; it also had social and even health implications.

In a society without antiperspirants, removing armpit hair was a practical way to reduce body odour, a serious concern in the public settings of Roman baths and gymnasiums.

Moreover, they often worked alongside other grooming professionals like barbers and masseurs. This collaboration formed an important part of Roman social life.

However, the job of an Alipilus was not glamorous. Often, they were slaves or people from lower social classes.

The work was tedious and probably unpleasant, but it was a specialised skill that could earn a decent fee, especially if they were known for their skill and gentle technique.

In some cases, wealthy families might even train a household slave specifically for this task.

This practice raised the role to a somewhat more respected position within the home.

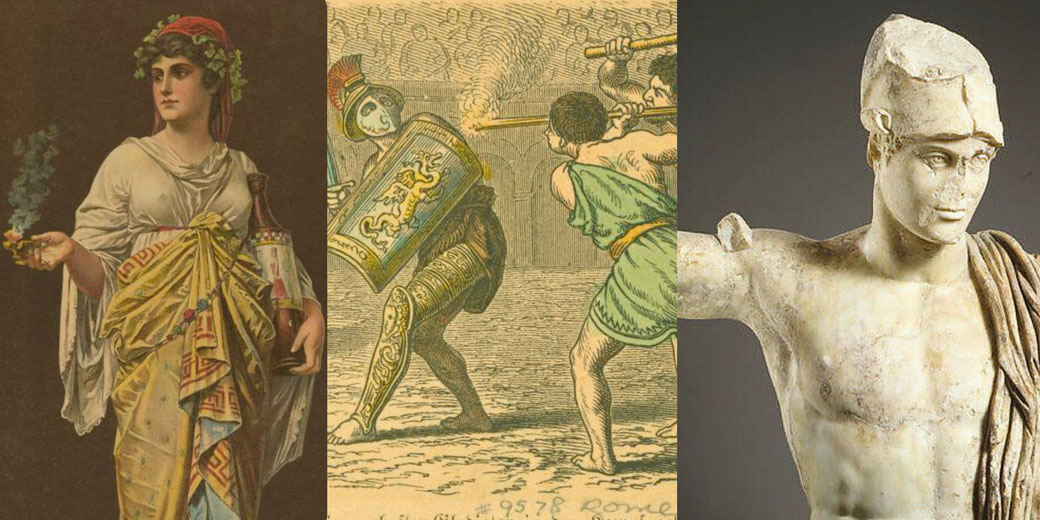

2. Vestal Virgin

The Vestal Virgins had a special role in ancient Rome. Because they came from powerful families, they carried unique responsibilities.

These women were chosen from well-known Roman families when they were young. They had great respect and influence rather than being wives or mothers.

Their job was to keep the sacred fire of Vesta, the goddess of the hearth, burning. They stood as a sign of Rome’s spiritual health.

They guarded a fire and stood as a sign of Rome’s spiritual health and safety.

Their vow of chastity was key to the state’s wellbeing. This gave their role significance beyond a simple ceremony.

Vestal life combined rights and strict rules. Also, they could learn, own land, and make a will. They could move freely in public and appear at events, where people saw their presence as a blessing.

They carried heavy duties, specifically that breaking their vow could anger the gods and harm the city. If a Vestal broke her vow, it could anger the gods and harm the city. The punishment was live burial.

In practice, leaders often sought their advice and could free prisoners. This shows the trust Rome placed in them.

After their 30 years of service, they could return to normal life and marry. Many found the change hard because of their long service and strict duties.

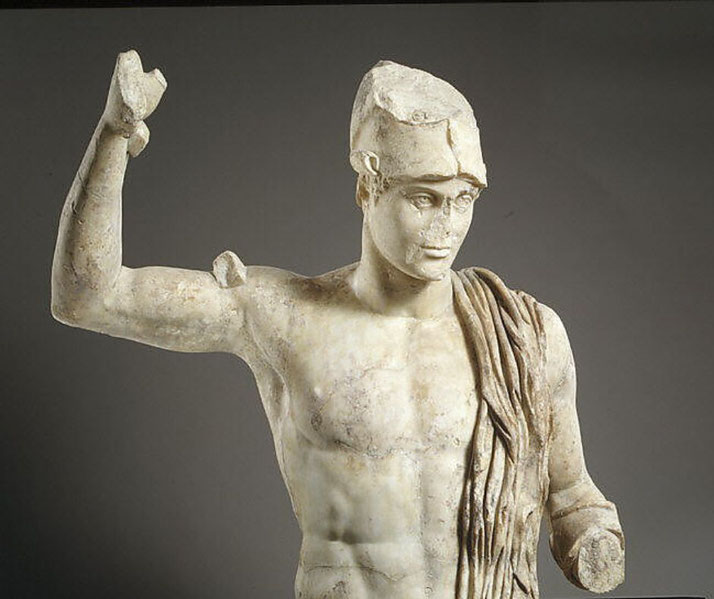

3. Gladiator's Sweat Scraper

Gladiators were the stars of their time while support staff handled many tasks behind the scenes. They were often slaves or prisoners of war. People talked about their fights and artists made their images.

Support staff had special jobs behind the scenes. One was the sweat scraper, or Strigilis.

The scraper removed sweat, dirt, and blood from gladiators after fights using a curved metal tool. Following that, the muscles received a massage with oils.

The scraper cleaned and relaxed muscles. They followed scraping with a massage and oils.

The Strigilis was part of the gladiator’s team, like a modern trainer. They helped the fighter perform and recover.

The tool itself could be finely made and show status. A skilled scraper was a real asset.

The job was not glamorous. Scrapers were usually slaves or low-status people. They needed skill to use the right pressure and method for different grime and wounds.

In a strange practice, people collected the sweat and oil scraped from famous gladiators. They sold the mixture as an aphrodisiac. They said it showed the fighter’s strength.

4. Public Toilet Attendant (Latrinarius)

Ancient Rome had a sophisticated sewerage system and public toilets commonly located near baths and markets.

These toilets stood near baths and markets. People from all classes used them.

The attendant, or Latrinarius, kept the toilets supplied with sponges on sticks. Romans used these instead of paper.

By guiding users and sometimes charging a small fee, attendants managed both order and revenue.

Their work helped limit disease and keep the community healthy.

Public toilets were also social spaces. People met and shared news there. The attendant was an informal news guide.

Despite the role’s importance, attendants were looked down on. They were often slaves or lower-class workers. The job was hard and not pleasant.

5. Funeral Clown (Archimimus)

In Roman society, where the line between sacred and everyday life was often blurred, the role of the Funeral Clown, or Archimimus, is one of the most interesting jobs.

At first glance, the idea of a clown in serious death rituals might seem out of place or even disrespectful.

However, Roman beliefs about the afterlife and the need for a proper farewell made the Archimimus an important figure.

These performers imitated the person who died by wearing masks and copying their behaviour as a way to honour and remember them. Specifically, this act highlighted the connection between the living and the dead.

They acted as a living memorial rather than perform for fun, capturing the person’s character in a way that stone memorials could not.

This was especially important for public figures, whose lives were seen as examples to follow.

By imitating the dead, the Archimimus helped highlight their good qualities and achievements. This form of storytelling kept the spirit of the person alive in people’s minds.

Romans believed the soul lived on after death and that a person’s qualities could continue through imitation.

They needed a deep understanding of the person they copied and the skill to show small details of their character in a respectful and engaging way.

They also had to handle the serious mood of a funeral, a place full of sadness.

They had to find the right balance between showing respect and holding attention, a task that called for both sensitivity and skill.

6. Food and Drink Taster (Praegustator)

The Food and Drink Taster, or Praegustator, acted as the first line of defence against poisoning attempts aimed at emperors, generals or other high-ranking officials.

This role involved great risk, since the Praegustator acted like a human shield by testing food and drink before someone more important could eat it.

In a society where political murder was not rare, the Praegustator was both protector and possible sacrifice.

They needed a good sense of taste and smell, together with knowledge of different foods and cooking methods.

They looked for small signs that might point to poison, and then used their training and experience to become trusted members of any noble household or imperial group.

Training and experience made the Praegustator a trusted member of any noble household or imperial group. Notably, their duties went beyond tasting and included overseeing meal preparation to ensure safety.

Their duties included overseeing meal preparation to ensure food came from reliable sources and was prepared under strict watch.

A Praegustator could receive rewards even with the risks, with some granted freedom when their master died as recognition of their loyal service.

Many were slaves or servants, but their special skills and the trust their masters placed in them could improve their social status.

Some were freed when their master died as a reward for loyal service.

The job could weigh heavily on them. The constant danger, the close watch on their work, and the life-or-death stakes made this a very stressful position.

7. Litter Carrier (Lecticarius)

In the busy streets of ancient Rome, where chariots, pedestrians and animals crowded together, a team of bearers carried a litter, or lectica, as a sign of status and privilege.

These litters were decorated with fancy designs and sometimes fitted with curtains for privacy. They were the choice of transport for the Roman elite, who could lie back and relax until they arrived. Litter Carriers, or Lecticarii, provided this service.

A smooth, comfortable ride was a sign of a skilled Lecticarius. The quality of the litter, the number of bearers and even how well they worked together showed the owner’s social standing.

Life as a Lecticarius was hard, requiring strength, stamina and coordination as the bearers moved together to keep the ride steady through crowded, rough streets.

Most were slaves or from lower social classes, so their well-being depended entirely on their employers’ wishes. Even so, becoming a Lecticarius remained a skilled profession learned through practice and training.

Despite these challenges, being a Lecticarius was a skilled job that people learned through practice and training.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.