7 of the weirdest and most disgusting jobs you could do in ancient Rome

Ancient Rome had some truly unusual jobs. The city was famous for its emperors and gladiators, but Romans performed tasks both strange and essential...

How to get a job in ancient Rome

In the busy streets of Rome and other major cities, one could find many different professions.

Artisans, traders, and merchants filled the marketplaces and sold everything from exotic spices to detailed jewellery.

Skilled workers like blacksmiths, carpenters, and masons were in high demand, especially for government construction projects.

Meanwhile, the Roman legions offered a different kind of employment, one that promised Roman citizenship upon completion of military service.

The legal profession was another path for social mobility, as skilled speakers could rise through the ranks to become influential senators.

Yet, not all jobs were equal. Social standing played a major role in determining the type of work someone could pursue.

The elite often held positions of power and influence, while the lower classes performed more menial, labour-intensive tasks.

While slaves, who were considered property rather than citizens, were often forced into the most difficult and degrading jobs.

1. Armpit Plucker (Alipilus)

It's easy to overlook the simpler professions that contributed to the daily life and wellbeing of the population.

One such job, which might surprise us today but was considered essential in ancient Rome, was that of the Armpit Plucker, or Alipilus.

This profession was part of the broader area of personal grooming, which was surprisingly advanced despite the technological limits of the time.

They were mainly responsible for removing unwanted body hair, especially from the armpits. They used tools such as tweezers and specialised waxes.

While the task might seem unimportant today, it was crucial to Roman beauty standards, which valued smooth, hairless skin as a sign of cleanliness and sophistication.

In a society without antiperspirants, removing armpit hair was a practical way to reduce body odour, a serious concern in the public settings of Roman baths and gymnasiums.

Moreover, they often worked alongside other grooming professionals like barbers and masseurs.

However, the job of an Alipilus was not glamorous. Often, they were slaves or people from lower social classes.

The work was tedious and probably unpleasant, but it was a specialised skill that could earn a decent fee, especially if they were known for their skill and gentle technique.

In some cases, wealthy families might even train a household slave specifically for this task.

This practice raised the role to a somewhat more respected position within the home.

2. Vestal Virgin

The Vestal Virgins had a special role in ancient Rome. These women were chosen from well-known Roman families when they were young.

However, they had great respect and influence since they had given up the opportunity of becoming wives or mothers.

Their main job was to keep the sacred fire of Vesta, the goddess of the hearth, burning. This flame was seen as a sign of Rome’s spiritual health.

Also, their vow of chastity was key to the state’s wellbeing. As a reslut, Vestal life combined rights and strict rules.

They could own land, and even write a lagel will. They could move freely in public and appear at events, where people saw their presence as a blessing.

Unfortunately, breaking their vow could anger the gods and harm the city. If a Vestal was found guilty of neglecting the fire or losing their virginity, the punishment was to be buried alive.

After their 30 years of service, the women could finally return to normal life and marry if they chose to.

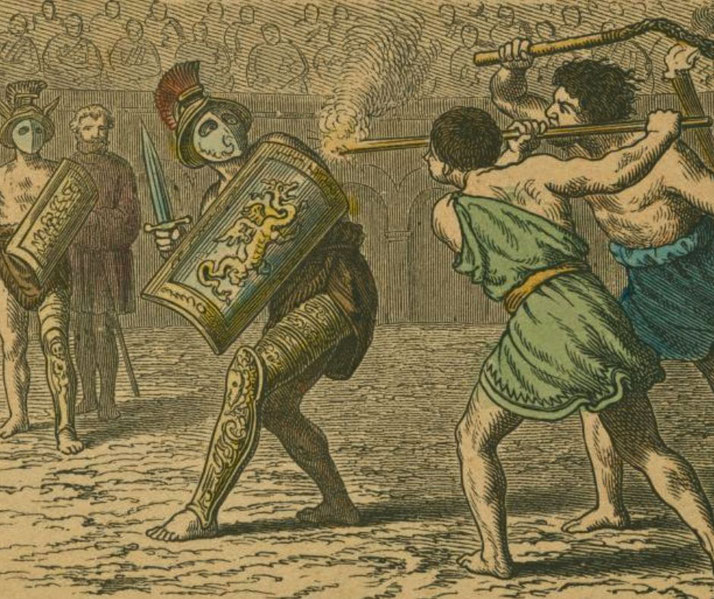

3. Gladiator's Sweat Scraper

Gladiators were the sports stars of their time. They were often slaves or prisoners of war.

However, there was a team of support staff that had special jobs behind the scenes.

One was the sweat scraper, or Strigilis. They removed sweat, dirt, and blood from gladiators after fights using a curved metal tool. Following that, the muscles received a massage with oils.

In a way, the Strigilis was part of the gladiator’s team, like a modern trainer. They helped the fighter perform and recover from difficult events.

Therefore, a skilled scraper was a real asset. However, the job was not glamorous.

Scrapers were usually slaves or low-status people. They also needed skill to use the right pressure and method for different grime and wounds.

In a strange practice, some Roman people collected the sweat and oil scraped from famous gladiators.

For this reason, the Scrapers sold the mixture as an aphrodisiac. They said it gave you some of the fighter’s strength.

4. Public Toilet Attendant (Latrinarius)

Ancient Rome had a sophisticated sewerage system and public toilets commonly located near baths and markets.

People from all classes used them. The attendant, or Latrinarius, kept the toilets supplied with sponges on sticks, since Romans used these instead of toilet paper.

By guiding users and sometimes charging a small fee, attendants managed both the orderly runnig of the site and generated substantial revenue.

If donen well, their work helped limit disease and keep the community healthy.

Public toilets were also social spaces. People met and shared news there. As a consequence, the attendant was an informal news guide.

Despite the role’s importance, attendants were looked down on. They were often slaves or lower-class workers.

5. Funeral Clown (Archimimus)

In Roman society, where the line between sacred and everyday life was often blurred.

The role of the Funeral Clown, or Archimimus, is one of the jobs that bridged these two parts of society.

At first glance, the idea of a clown in serious death rituals might seem out of place or even disrespectful.

However, Roman beliefs about the afterlife and the need for a proper farewell made the Archimimus an important figure.

These performers imitated the person who had died by wearing masks and copying their behaviour as a way to honour and remember them.

They acted as a living memorial rather than perform for fun, capturing the person’s character in a way that stone memorials could not.

This was especially important for public figures, whose lives were seen as examples that should be emulated.

By imitating the dead, the Archimimus helped highlight their good qualities and achievements.

Romans believed the soul lived on after death and that a person’s qualities could continue through imitation.

Therefore, they needed a deep understanding of the person they copied and the skill to show small details of their character in a respectful and engaging way.

However, they had to find the right balance between showing respect and holding attention, a task that called for both sensitivity and skill.

6. Food and Drink Taster (Praegustator)

The Food and Drink Taster, or Praegustator, was the first line of defence against poisoning attempts aimed at emperors, generals or other high-ranking officials.

Clearly, this role involved great risk, since the Praegustator consuemed food and drink before anyone more important could eat it.

In a society where political murder was not rare, the Praegustator little put their life on the line every meal time.

As part of their duties, they needed a good sense of taste and smell, together with knowledge of different foods and cooking methods.

They looked for small signs that might point to poison, and then used their training and experience to become trusted members of any noble household or imperial group.

Their duties often included overseeing meal preparation to ensure food came from reliable sources and was prepared under strict watch.

A Praegustator could receive some substantial rewards, with some granted freedom when their master died as recognition of their loyal service.

Many were slaves or servants, but their special skills and the trust their masters placed in them could improve their social status.

However, the constant danger, the close watch on their work, and the life-or-death stakes made this a very stressful position.

7. Litter Carrier (Lecticarius)

In the busy streets of ancient Rome, where chariots, pedestrians and animals crowded together, a team of bearers carried a litter, or lectica, was a sign of privilege.

These litters were decorated with fancy designs and sometimes fitted with curtains for privacy.

They were the choice of transport for the Roman elite, who could lie back and relax until they arrived. Litter Carriers, or Lecticarii, provided this service.

A smooth, comfortable ride was a sign of a skilled Lecticarius. The quality of the litter, the number of bearers and even how well they worked together showed the owner’s social standing.

Life as a Lecticarius was hard, requiring strength, stamina and coordination as the bearers moved together to keep the ride steady through crowded, rough streets.

Most were slaves or from lower social classes, so their well-being depended entirely on their employers’ wishes.

Even so, becoming a Lecticarius remained a skilled profession learned through practice and training.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.