13 of the weirdest facts about King Tutankhamun

If people know anything about ancient Egypt, it is usually that there was a boy pharaoh called Tutankhamun. However, few know much more than the name of this young pharaoh.

He lived a brief but important life which left quite a few questions that are still not fully answered, even a century after the discovery of his tomb in 1922.

Here are the strangest but true things about King Tut...

1. He was only a child when he became pharaoh

King Tutankhamun, commonly known as King Tut, ascended to the throne of Egypt at the very young age of 9.

Because he lacked experience, he was guided by powerful advisors. Among those advisors were the Grand Vizier Ay and the General of the Armies, Horemheb.

In spite of his youth, his was required to govern a large and powerful empire. During his brief reign, there were a series of important events that unfolded.

One of the most significant of these was the religious restoration that followed his father’s introduction of monotheism.

Tutankhamun oversaw the return to the tradiational Egyptian religous practices, including the reintroduction of hundreds of gods.

2. Mysterious death

The exact nature of King Tutankhamun’s death remains one of the most puzzling mysteries of ancient Egypt.

According to available evidence, he died around the age of 18 or 19. Historians and archaeologists have provided a range of theroies about his sudden demise.

Early X-rays of his mummy revealed an anomaly in his skull once thought to be a blow to the head from someone hitting him with a solid object.

However, later CT scans did not confirm any fatal fracture. Instead, modern CT scans and DNA analysis subsequently pointed to a serious leg fracture, possibly resulting from a riding accident that may have led to infection.

Those same studies also noted the presence of malaria parasites.

Also, King Tut’s tomb appears to have been prepared in haste: its smaller size and unfinished decorations suggest a rushed effort.

So, some scholars believe that this hasty burial resulted directly from a sudden and unexpected death.

Given the lack of records from his time detailing his passing, the mystery deepens.

Over time, conspiracy theories, wild guesses, and even fictional accounts have filled that gap in information.

3. He was probably inbred

One of the strangest revelations from various DNA and medical examinations of the Tutankhamun mummy is that he was a child of a complex and somewhat unsettling aspect of royal life in ancient Egypt: inbreeding.

Genetic studies conducted on King Tut’s mummy show that his father, Pharaoh Akhenaten, and his mother were full siblings.

Although this practice may shock modern readers, royal incest was not uncommon in ancient Egypt.

It was used to preserve what the Egyptians believed was their 'sacred bloodline' and the divine nature of the pharaohs.

4. He lived with a lot of health problems

Several generations of inbreeding resulted in the young King Tutankhamun suffering from multiple physical health problems.

Modern examinations of his mummy uncovered evidence of a clubfoot, a condition that would have required him to use a cane to walk.

This finding is supported by the discovery of over 130 walking sticks in his tomb.

Genetic studies also identified an anomaly in his navicular bone, which is a small, boat-shaped bone located on the inner side of the midfoot.

While some experts once called this condition Kohler disease, others now believe it was simply a congenital underdevelopment.

Either way, that bone issue may have caused chronic pain. Regardless, King Tut was often depicted in art and sculptures as a strong and lively ruler.

In contrast, the reality of his physical condition adds another layer of detail to our understanding of his life and reign.

5. His burial was suspiciously rushed

The tomb of King Tutankhamun is renowned for its impressive treasures, but it is actually very unassuming.

Its relatively small size and the presence of unfinished and reused artefacts suggest that people didn't invest a lot of time in burying the king.

Some Egyptologists suggest that the tomb may have been repurposed after his death, though this idea remains under debate.

As such, the rushed burial may explain why some items seem out of place or are not customised for King Tut.

This sense of urgency contrasts sharply with the careful preparations that usually accompanied a royal burial, a process that often took many years.

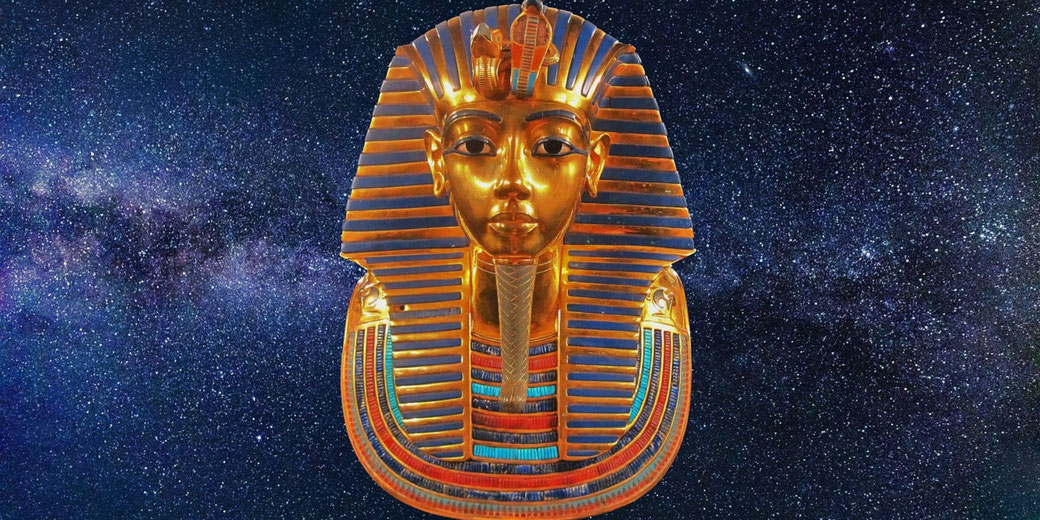

6. He was buried in a solid gold sarcophagus

King Tutankhamun’s golden coffin is celebrated as one of the most beautiful and memorable artefacts of ancient Egypt.

Crafted from 110 kilograms of pure gold, the coffin displays a shining image of the young pharaoh that likely aimed to capture his likeness with clear detail.

In ancient Egyptian belief, gold symbolised the gods and eternity. In fact, this coffin was one of three nested within each other, with the innermost being the golden one.

Howard Carter first discovered the golden coffin in 1922; his amazement at its sight has become part of the discovery’s lore.

7. He was the origin of the 'pharaoh's curse'

Legends of curses on tombs existed long before Tutankhamun, but the discovery of his tomb in 1922 by Howard Carter revitalised that idea.

Just after the tomb was opened, a number of members of the excavation team and those associated with the discovery began to die under mysterious or unusual circumstances.

The story that became known as the “Curse of the Pharaoh” captured global attention after Lord Carnarvon, the expedition’s financial backer, died of an infected mosquito bite shortly after the tomb opened.

Newspapers and storytellers linked those deaths to the curse. Today, many of these claims have been shown to be false and can be attributed to natural causes or simple coincidence, but the legend endures in the popular imagination.

8. He was buried with his two, deceased daughters

One of the most moving discoveries within King Tutankhamun’s tomb was the presence of two small coffins containing the mummified bodies of infants who were either stillborn or died shortly after birth.

Genetic testing and analysis identified these infants as the daughters of King Tut.

Placed close to their father in his eternal resting place, these tiny mummies highlight the importance of family within the royal line and the hope for rebirth and reunion in the afterlife.

Some scholars propose that genetic complications, possibly related to the royal family’s practice of intermarriage, might have led to their early deaths, though the exact cause remains uncertain.

9. His beard was broken

Among the many treasures unearthed from King Tutankhamun’s tomb, the golden funerary mask is probably the most recognisable.

Yet that mask’s blue-and-gold braided beard was accidentally broken off during a cleaning procedure at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

The incident occurred in 2014 and led to a hasty attempt to reattach the beard with epoxy glue.

That effort caused further damage to this priceless artefact, and the botched repair became a worldwide controversy.

Later, a team of German and Egyptian experts undertook a more careful restoration.

Their successful reattachment of the beard has preserved the mask’s condition for future generations.

10. There may be hidden chambers in his tomb

The discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922 was a major moment in archaeological history, but the mysteries did not end after the initial unveiling.

Radar scans conducted in 2015 suggested the possibility of hidden chambers adjacent to his burial chamber.

However, more recent studies have failed to confirm any voids. While these potential chambers could hold clues to further treasures or even the resting place of other royal figures such as Queen Nefertiti, the evidence remains inconclusive.

11. His tomb had the only surviving Egyptian trumpets

Among the myriad of treasures unearthed from King Tutankhamun's tomb, one artifact resonates quite literally with the sounds of ancient Egypt: a rare trumpet, one of the oldest playable musical instruments in the world.

This trumpet, made from silver and gold, earned praise from archaeologists for its fine workmanship.

It was played during a 1939 radio broadcast when listeners at that time reported being moved by its tones.

By offering a rare auditory link to the past, the trumpet allows us to hear the sounds of the world that King Tut once knew.

12. The real reason his tomb had been hidden

The Valley of the Kings is a long burial ground on the west bank of the Nile and was the final resting place for many of Egypt’s most famous pharaohs.

The location of King Tutankhamun’s tomb within this valley is particularly notable because it lay beneath the entrance to Ramses VI’s tomb and was covered by debris left by ancient robbers.

In part because of this placement, the site remained hidden until 1922. Some scholars believe that the tomb’s hidden position was a deliberate choice, perhaps prompted by the young king’s unexpected death and the quick need for a suitable burial site.

Others argue that it was simply a protective measure to keep the tomb safe from damage.

Whatever the case, that placement became the tomb’s greatest defence against time and intrusion.

13. He owned an object from outer space

The most interesting of all the treasures of King Tutankhamun's tomb, is one with cosmic connections: a dagger made from meteoritic iron.

This beautifully crafted weapon, with a blade of shimmering metal and a gold handle adorned with intricate detailing, is believed to have been forged from a meteorite that fell to Earth.

Modern analysis of the blade's composition confirmed the presence of nickel and cobalt, elements that are commonly found in meteorites.

In ancient Egypt, meteorites were seen as gifts from the gods, and their iron, often referred to as "iron from the sky", was considered more precious than gold.

The meteorite dagger, therefore, shows the deep spiritual and cosmological significance they placed on objects from the heavens.

As a result, n the hands of a young pharaoh, this dagger was both a tool of protection and a symbol of his divine right to rule.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.