What the Titanic's passengers ate: How menus varied dramatically based upon social class

Billed as the most luxurious ship of its time, the Titanic promised its passengers an exceptional experience as they journeyed across the Atlantic on their way to New York.

However, the experience onboard varied significantly based on each person's social standing in Edwardian society. As a result, first-class passengers dined in lavish splendour with menus that were crafted by expert chefs, while those in third class shared simple, filling meals that were designed to sustain them during their voyage.

But just how wide this gap was is quite surprising to us over 100 years later.

First-class dining: Luxury at sea

Guests who paid the highest fares on the Titanic entered an elegant dining room that was decorated with detailed woodwork and gleaming chandeliers.

The most expensive first-class ticket on the Titanic cost £870, equivalent to around $100,000 today.

Men and women who were dressed in their finest clothing adhered to the Edwardian expectations of fashion and manners.

White-gloved, highly trained stewards moved silently between tables as they presented sophisticated courses to the wealthiest passengers.

The dining room's atmosphere was refined with soft music that was played by the ship’s live orchestra, which created a peaceful setting for conversations between prominent businessmen like John Jacob Astor and Benjamin Guggenheim.

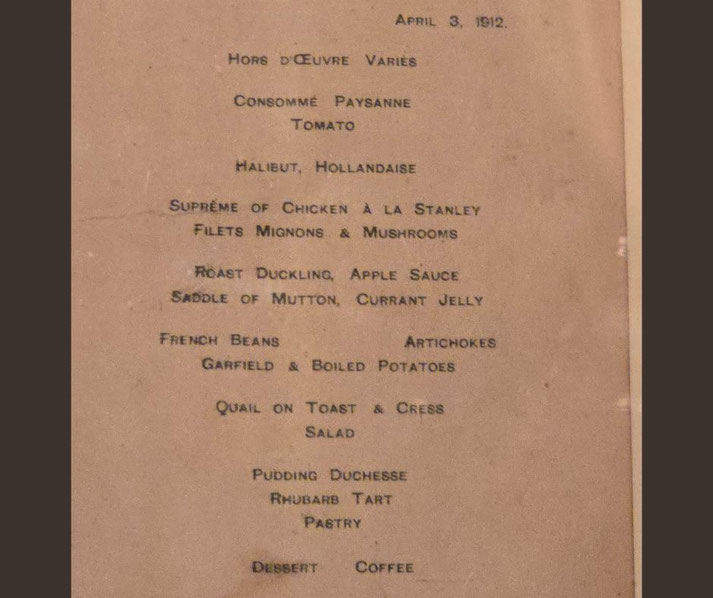

The gourmet menus that were served to first-class passengers were meant to represent the peak of culinary refinement.

Dishes such as fresh oysters, tender filet mignon and roasted duckling were followed by rich desserts like pudding duchesse and chocolate éclairs.

Simply put, the multi-course meals were designed to mirror the luxury these passengers were used to on land.

As was fashionable at the time, French cuisine dominated the diverse selection, from the sauces to the wine pairings, to enhance the dining experience.

Famous first-class passengers Lady Duff Gordon and Isidor Straus would have chosen their meals from menus that resembled a guide to elite fine dining.

For many, dining in first class was about being seen among the top tier of elite travellers.

The exclusive social setting created an informal competition with status confirmed through conversation and displays of wealth.

Aristocratic Edwardians Countess of Rothes and millionaire Charles Hays, who were seated among fellow aristocrats and business leaders, enjoyed multi-course meals that were served on fine china and sterling silver.

Every bite was a vivid reminder of the huge gap between those who could afford luxury and those below deck.

Second-class dining: A taste of comfort

In comparison, second-class dining aboard the Titanic offered passengers a comfortable experience though it lacked the extravagance of the first-class meals.

The modestly furnished second-class dining room seated passengers, mostly skilled professionals, dedicated educators and hardworking middle-class families.

Unlike first-class diners who enjoyed elaborate meals, second-class passengers ate simpler but satisfying food with more focus on practicality than indulgence.

The hearty meals that were well-prepared appealed to more traditional tastes as they moved away from the French influences that were seen in the first-class menu.

These passengers ate dishes like roast turkey, curried chicken and spiced plum pudding with generous and hearty portions.

There was a focus on filling meals that matched the fact that many second-class passengers were used to more modest home-cooked food.

Breakfasts often included warm porridge, salty ham and eggs and fresh bread that provided a sense of familiarity and comfort.

While there were fewer courses than in first class, the balanced meals were still nourishing.

The welcoming, more casual second-class dining space allowed passengers to sit at shared tables so dining became a social event where conversations came easily.

The absence of strict dining rules created a more relaxed setting with a continued sense of order and politeness.

Prompt and organised service let passengers enjoy their meals without the complicated customs that were found in the upper-class dining rooms.

Second-class passengers regarded this combination of good food and a pleasant setting as a source of comfort during the journey.

Third-class dining: Simplicity and sustenance

Third-class passengers, around 700 in total, were mostly European immigrants from countries such as Ireland, Sweden and Italy who were looking for a new life in America.

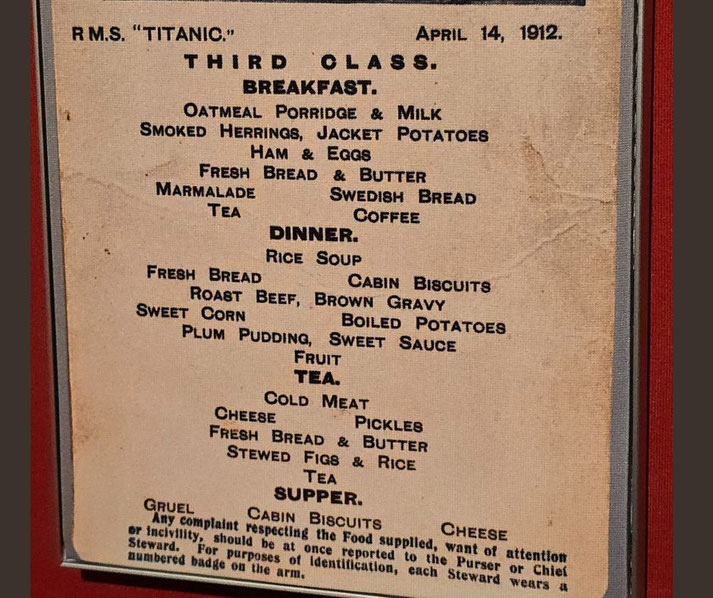

Their daily meals were basic and filling, which provided enough food for the long transatlantic trip.

Breakfasts usually included plain oatmeal, cold milk and dry biscuits while lunches and dinners featured simple but hearty dishes like boiled beef, potatoes and crusty bread.

The food, although plain, was fresh and enough to keep passengers well-fed throughout the voyage.

While first- and second-class passengers enjoyed varied meals and gourmet items, steerage passengers received more standard servings of staple foods.

These meals excluded rich sauces and fancy presentation that were seen in the others, but the essential items were offered.

There was little variety and desserts were simple, often stewed prunes or rice pudding.

The plain menu that focused more on practicality and durability ensured passengers had enough to eat even with limited resources.

Most importantly, the shared third-class dining experience brought passengers together in large common areas.

These functional spaces, which lacked the polished finish of first class and the modest charm of second class, could seat around 300 people at once and created a busy and lively setting.

Meals that were served at scheduled times brought passengers together at long wooden tables and encouraged conversation and a feeling of community among travellers from different backgrounds.

Did they cater for special dietary considerations?

Although the Titanic’s diverse passengers came from many countries and backgrounds, there was no wide effort to offer meals for specific cultural tastes.

Italian and Eastern European immigrants, who made up a large portion of the third-class passengers, ate the standard meals that were given to all in steerage.

Some first-class passengers who preferred particular European cuisines could request specific dishes or rare ingredients thanks to the flexible service that was offered in their dining room.

That said, limited accommodation for special dietary needs existed particularly for religious requirements.

Jewish third-class passengers received kosher meals that were prepared according to Jewish dietary laws using separate utensils and cooking tools to avoid mixing meat and dairy.

Although the options were simpler than what others received, kosher meals showed an effort to meet the religious needs of an important group.

Passengers who needed specific food for health reasons such as diabetics or those with digestive issues had to make special requests.

Wealthy first-class passengers could rely on the skilled kitchen staff to make changes to their meals.

For most passengers, especially in third class, such accommodations were uncommon.

What did the crew eat on the Titanic?

The crew aboard the Titanic, like the passengers, ate meals that matched their role on the ship and the class system.

The ship's crew included 899 people, from senior officers and skilled engineers to stewards and stokers.

The higher-ranking officers ate in their own dining room and were given food that was filling and varied.

They had solid dishes like roast meats, potatoes, and vegetables, which gave them the energy needed for their tough work schedules.

For the long-shifted, physically drained general crew, especially those in the boiler rooms, they needed hearty food to keep up their strength.

Their meals usually included basics like boiled beef, soup, bread, and porridge.

Such a basic meal plan gave them enough energy for the hard jobs they did every day.

Breakfasts often included items like oatmeal and tea, which provided a simple but useful start to their long workdays.

The kitchen staff made meals for the crew in a separate galley, which helped ensure the food was cooked efficiently for such a big group of workers.

The crew’s meals were eaten in a shared mess hall with little time for relaxed eating.

Crew members who ate together quickly went back to their jobs, knowing the ship depended on their constant work.

How much food was on the Titanic?

The Titanic carried over 75,000 pounds of fresh meat, 40,000 eggs, and 1,500 gallons of milk, among many other items.

A massive food inventory was stored in different compartments around the ship, including large, refrigerated rooms to keep fresh food cold.

These below-deck areas cooled by the air helped keep meats, dairy, and fresh produce from spoiling.

Dry goods like flour and sugar were kept in separate rooms, and managing these supplies took careful planning, since chefs had to avoid waste and still meet the needs of passengers in all three classes.

The chefs and kitchen workers on the Titanic had a major job, as they had to make sure first-class passengers got the high-quality food they expected.

The large kitchen staff cooked for the 324 first-class diners, 284 second-class passengers, and 709 in third class, and making food for that many people was a big task.

The kitchen team had to use several galleys which were kitchens placed on different decks to feed each class.

These galleys, which had up-to-date equipment for the time, included electric toasters and machines to peel potatoes.

A multi-galley system, which let the Titanic offer a range of meals to its passengers, functioned even though it was in the middle of the Atlantic.

The last meal on the Titanic

On the night of the 14th of April, 1912, people on the Titanic sat down for what would be their last meal:

In the first-class dining room, the final dinner was an elaborate 10-course meal.

Oysters, consommé Olga, and filet mignon were some of the dishes served, and wine was poured freely, with the room full of talk about business, travel, and the anticipation of the journey.

The service went on into the night, with some passengers heading to the smoking room or their suites.

In second class, passengers ate roast turkey with cranberry sauce, green peas, and boiled potatoes. Dessert included plum pudding and American ice cream.

As they finished their desserts and tea, many second-class passengers went to the library or promenade deck, unaware that their peaceful meal would be their last before the disaster to come.

For the third-class passengers, many of whom ate earlier in the evening, they got filling meals like roast beef, boiled potatoes, and bread.

After dinner, they spent time in shared spaces or went back to their bunks, and when the ship hit the iceberg later that night, these passengers, along with those from the upper decks, were thrown into chaos no meal could prepare them for.

That night, after the Titanic's passengers left the dining rooms, the plates and silverware were left behind, never to be used again.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.