How the discovery of the Rosetta Stone finally helped us crack the riddle of the hieroglyphs

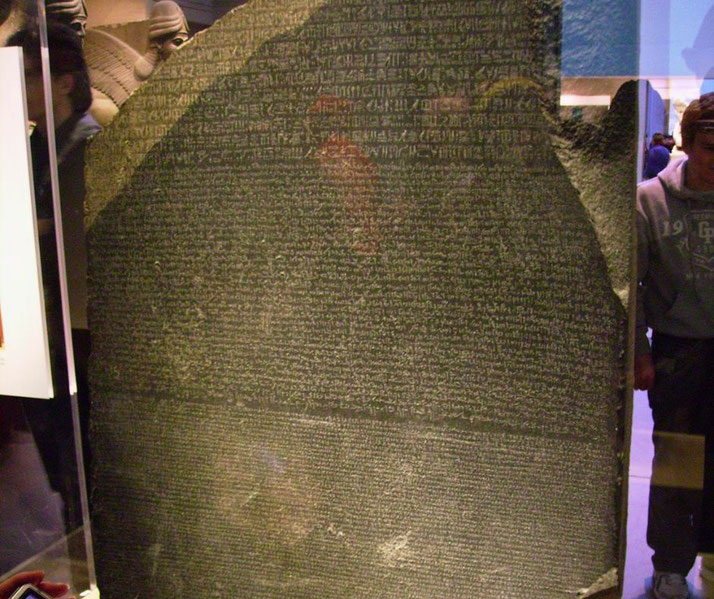

The Rosetta Stone is one of the most well-known and familiar objects in the world, but its history and importance go far back into ancient history.

From its rediscovery by French soldiers during Napoleon’s campaign in Egypt to the way it helped us read ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, the Rosetta Stone has interested everyone, from scholars to tourists.

Here, we look into the story behind the Rosetta Stone and examine its historical background, the information it contains and the part it played in teaching us how to read one of the world’s oldest and most mysterious writing systems.

What is the Rosetta Stone?

The Rosetta Stone is a large piece of stone inscribed with an official order from Memphis in 196 BCE, during the rule of Ptolemy V Epiphanes.

It was made as part of a larger stone for a temple at Memphis, though some evidence suggests it may have been moved to Sais in the Nile Delta region.

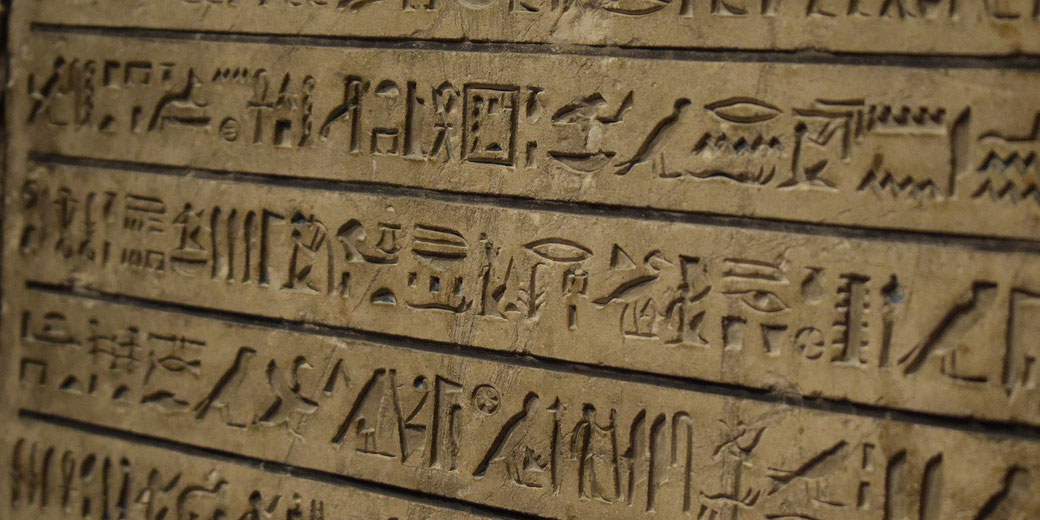

The order is written in three ways of writing: ancient Greek, Demotic and hieroglyphs.

Ptolemy V Epiphanes, the ruler behind the order on the stone, was part of the Ptolemaic dynasty that took control of Egypt after Alexander the Great’s death and whose first ruler officially became pharaoh in 305 BCE.

The Ptolemies were Greek rulers over an Egyptian population, so they adopted many Egyptian customs and practices.

At that time, they also had to deal with the threat of attack by foreign powers, including the Seleucids; Roman influence in Egypt did not become a threat until after 168 BCE.

What did the inscription say?

The order on the Rosetta Stone is a royal message given in Memphis, an important city in Egypt, in 196 BCE.

It was written in three ways of writing, as mentioned earlier, so that all people in Egyptian society could read and understand it.

Specifically, the ancient Greek writing was used by the ruling class, the Demotic writing was used for everyday writing and legal papers, and the hieroglyphs were used by priests and educated people.

That message is not especially important for history, since it mainly deals with tax breaks for priests.

Even so, it is the fact that the message is written in three different ways that makes it so important.

The ancient Greek writing was already known and understood, but the Demotic and hieroglyphic writing were not.

This meant that the Rosetta Stone gave scholars the key to learning how to read ancient Egyptian writing.

Forgetting how to read hieroglyphs

The use of hieroglyphs decreased in Egypt during the 4th century CE, as the country gradually converted to Christianity and the use of Greek and Coptic writing became more common.

By the end of the 4th century, hieroglyphs were no longer used as a written language.

Over the years that followed, knowledge of how to read hieroglyphs was slowly lost, and the writing became full of mystery and misunderstanding.

By the medieval period, people saw hieroglyphs as magical signs with mysterious powers, rather than a system of writing with clear meaning and purpose.

Interest in hieroglyphs started again during the Renaissance, as European scholars began to study the ancient societies of Greece, Rome and Egypt.

Its rediscovery

Everything changed when the French general, Napoleon, invaded Egypt in 1798.

He led his forces there to try to set up a French presence in the Middle East and to hurt British trade in the region.

He saw the campaign as a chance to spread French influence, open up new trade routes and create a base from which he could attack British-controlled India.

Napoleon’s invasion was driven mainly by strategic and trade goals, though he did bring scholars to study Egypt’s ancient culture as a secondary goal.

Then, in 1799, the Rosetta Stone was found by a French army officer named Pierre-François Bouchard during Napoleon’s campaign in Egypt.

Bouchard was with a group of soldiers who were fixing a fort near the town of Rosetta (now called Rashid) when they came across the stone, which had been reused as part of a wall.

At that time, people did not realise how important the stone was and it was treated as just another old object.

After the French were defeated in Egypt, the Rosetta Stone was taken by British forces in 1801 and moved to England.

How it was used to decipher hieroglyphs

t was not until a few years later, when scholars began to study the stone carefully, that they saw its true importance.

Soon after, one of the first scholars to take an interest in the Rosetta Stone was the British scholar Thomas Young.

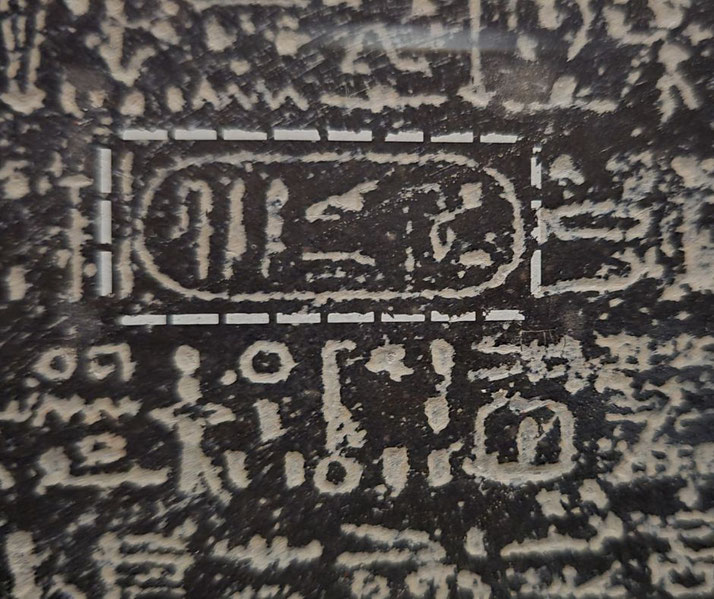

In 1814, Young published a paper in which he compared the hieroglyphs on the stone with the Greek and Demotic writing, and he made some key observations.

He noticed that some of the hieroglyphs were inside an oval form, and he suggested that these ovals might hold the names of rulers.

Young’s work was followed by that of the French scholar Jean‑François Champollion, who is now seen as the founder of Egyptology.

Champollion was very interested in the hieroglyphs on the Rosetta Stone, and he spent years in careful study of them.

He focused on the ovals around certain signs, and he eventually found that they did hold the names of rulers.

This let him recognise some of the kings and queens of ancient Egypt and to start reading the hieroglyphic writing.

Ultimately, Champollion’s major discovery came in 1822 when he said he could read royal names in these ovals, though he did not publish his full guide until 1824.

He used the ovals on the Rosetta Stone, along with other texts, to find the names of some rulers and then work out the sounds of some hieroglyphs.

From there, he was able to put together the meanings of other hieroglyphs and read more texts.

Rosetta Stone's significance

Champollion’s work in reading the hieroglyphs opened up a whole new world of knowledge about ancient Egypt.

For centuries, hieroglyphs were a mystery and scholars had been unable to read them.

Now, for the first time, they could understand the written language of one of the world’s oldest and most interesting societies.

Today, the Rosetta Stone is kept in the British Museum in London and is still an important historical object that gives valuable information about the politics, religion and culture of ancient Egypt.

Since the early 2000s, Egypt has repeatedly asked for the Rosetta Stone to be returned because it is very important to the Egyptian people.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.