Who were the 12 Olympian gods?

More than 2000 years since the end of the ancient Greeks, their gods remain very popular, with many books, TV shows, films and video games made about them.

These gods were thought to live on the mist-covered peaks of Mount Olympus, and twelve are still familiar names today.

They were believed to influence things such as war and the annual harvest. In particular, they represented the best qualities and worst faults of people, with their surprising stories of deeds, rivalries and relationships that formed the basis of Western mythology.

But who exactly were the 12 Olympian gods?

The origins of the Olympians

Legend holds that the Olympian gods came to power after a violent battle with the older Titans, known as the Titanomachy.

This event is said to have happened in a time before human history, showing how order was set up in the world.

This conflict is told by poets such as Hesiod and Homer. Specifically, Zeus led his brothers and sisters in a ten-year fight against their predecessors, among whom was their father Cronus.

Zeus, with Hera, Poseidon, Demeter and Hestia, formed a new group of gods on Mount Olympus, while Hades ruled the underworld.

Following this victory, they assigned roles among themselves, each looking after different parts of the world and human life.

In his writings, Hesiod clearly described how their actions controlled the feelings and actions of many humans rather than controlling nature.

For example, Athena became known for her wisdom and careful military strategy, while Ares showed the violent side of war.

In this way, the gods represented both positive qualities and negative faults that reflected the societies that worshipped them.

Many myths and stories about these gods showed their relationships with each other and their interactions with humans.

Among these stories were tales of love, betrayal and bravery. From Hermes’s cleverness to Hera’s anger against Zeus’s human lovers, the detailed stories of the Olympian gods fill many pages of ancient literature.

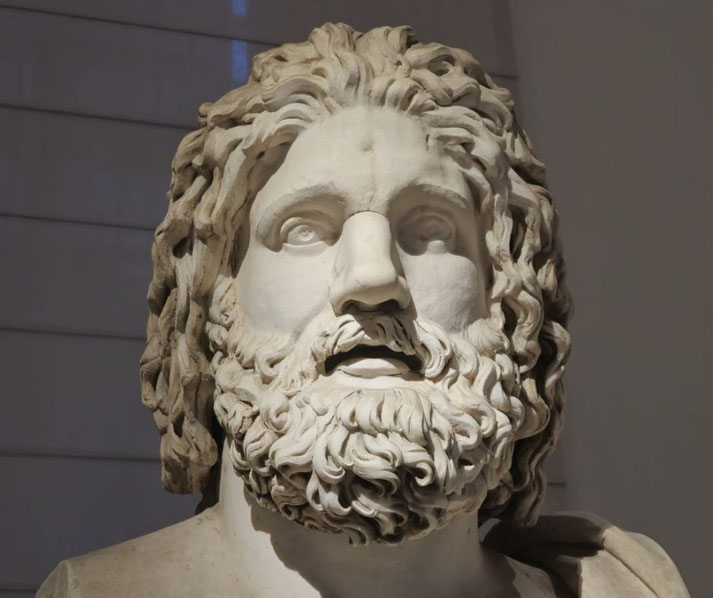

1. Zeus

Zeus was the most powerful of the Olympian gods, ruling the sky and using a thunderbolt as his main weapon; he was often shown with an eagle and a staff, symbols that showed his power over both the sky and the earth.

His control over weather and natural events showed his role as judge of both gods and humans.

As king of the gods, he was often asked to solve arguments among the other gods on Mount Olympus and make sure that divine rules were followed.

His titles, such as "Cloud-gatherer" and "Thunderer", had important religious and cultural meanings.

For example, as the "Cloud-gatherer", he controlled the weather, which was vital for farming and survival.

However, he was famous for his many romantic affairs, which were important stories in myths and lessons.

From these affairs, many demigods and heroes were born, such as Hercules and Perseus, each of whom showed qualities of their godly father.

2. Hera

Hera was Zeus’s wife and his sister, and in this role, she was queen of the gods and looked after marriage and family, which were key parts of ancient Greek society.

Her authority also covered loyalty and the role of women in the home.

She was respected as a protector of married women and was worshipped at many temples in Greece. One of the most famous was the Temple of Hera on Samos.

Notably, Hera’s marriage to Zeus and his many affairs were main stories in Greek myths.

Because of her husband’s unfaithfulness, she often took revenge on his lovers and their children.

Her actions were her way of punishing those she viewed as having done wrong and of seeking justice.

The Greeks likely used these tales to look at power within families and how one person’s actions can affect future generations.

3. Poseidon

Poseidon was Zeus’s brother and was the god of the sea.

In that capacity, his power covered all waters, which affected sailors and cities that depended on trade by sea.

These people both respected and feared him; his anger could cause great damage.

This power was seen in the waves of the sea and in his ability to cause earthquakes.

His trident was his most well-known weapon, which showed his power to move the sea and bring storms.

In cities such as Corinth and on many islands, there were shrines to him along the coast, especially where sailors asked for his protection for safe journeys.

Interestingly, his link to horses is less well known but still important. He was said to have created the first horse, which was valued for its strength and speed.

In one famous myth, when he struck the ground with his trident, he created a spring of salt water, but Athena offered an olive tree that the Athenians thought was more useful, so they chose her gift.

4. Demeter

Demeter was the caring goddess of farming and the harvest. For example, she looked after the growth and care of crops.

Her festivals, such as the Thesmophoria, were mainly held by women and showed how important she was for good harvests and fertility.

Her best-known story tells how Hades, the god of the underworld, kidnapped her daughter, Persephone, and, because of that, the four seasons began.

Because she grieved, she caused all plants to die and brought about a lifeless winter.

When Persephone returned, the earth grew green again, starting spring and summer. Later, the Eleusinian Mysteries built on her story.

The Eleusinian Mysteries were secret ceremonies in her and Persephone’s honour at Eleusis. People took part in rituals that offered rewards after death.

These ceremonies were among the most important in ancient Athens and lasted for more than a thousand years.

Because of this, her role as a giver of life and a link to the afterlife made her a lasting figure in Greek religion and myth.

5. Athena

Athena was likely the most famous Greek goddess after Zeus. She was his daughter.

She was the respected goddess of wisdom, war, and crafts.

She was born fully armed from Zeus’s head, showing she was a god of planned war rather than just great strength.

She protected cities, especially Athens. For example, the city was named after her and the Parthenon was built as a large temple for her.

The olive tree she gave the city became a symbol of peace and wealth, and was central to Athenian life.

One of her titles, 'Pallas', means her fighting strength and protective power. In art, she is often shown with a shield and spear.

Yet her wisdom went beyond war. She was also the patron of crafts, especially weaving.

Her skills in both thought and practical work made her a model for craftsmen and generals.

Because of this, every four years in Athens, people held the Panathenaic Festival to honour her with sports and music contests.

This festival was a key part of Athenian life. It celebrated her role in shaping society and supporting the city with ceremony and pageantry.

6. Apollo

Apollo was the god of the sun, music, poetry, and prophecy. As a result of his birth on the sacred island of Delos, he became a god linked to both nature and culture.

He is often shown with a lyre, and he played beautiful music that impressed gods and people and inspired art and oracles.

Also, at Delphi, where his main oracle was, people from all over Greece came to ask for his predictions.

This site was seen as the centre of the world because it had the navel stone, or omphalos, and was one of the most important religious places in the ancient world.

Later, the Pythian Games at Delphi, which were held for him, drew musicians, poets, and athletes.

7. Artemis

Artemis was the fierce goddess of the hunt, wild places, and childbirth.

She travelled forests with her group of nymphs and carried a bow and arrows as both protector and hunter.

In many stories, she was the best huntress, and her arrows could bring sudden death or offer mercy.

Although she was a virgin, she was also honoured as a goddess of childbirth because she helped women in labour. This shows she was both a giver of life and a taker of life.

In temples like Brauron in Attica, young girls served her as Arktoi or little bears.

Because of this, they took part in ceremonies that marked the change from childhood to adulthood.

Her most famous festival was the Brauronia, which included races and dances by young girls.

These ceremonies honoured her as a protector of children and as one who helped with safe life changes.

8. Ares

Ares was the god of war who showed the cruelty and violence of fighting in Greek myth.

Unlike Athena, who stood for planned war, Ares stood for the wild and destructive side of battle.

He took pleasure in the noise and bloodshed of war; in fact, his companions were Terror (Deimos) and Fear (Phobos), who went with him into battle.

Even though he was a war god, he was not worshipped everywhere in Greece.

However, people in areas like Thrace, which was known for its fierce fighters, honoured him more.

There, soldiers admired and called on his aggressive nature for strength in battle.

Although few worshipped him, he appears in works like Homer’s Iliad as less noble than other gods.

He came to represent the uncontrolled and dangerous side of war; at the same time, it warned people about the extremes of violence.

Festivals like the Spartan Chalcioecus were held for him, which praised his strength and the state’s military skill.

This shows the mixed view of Ares: often looked down on, but still an important part of how ancient Greeks saw war and its effects.

9. Aphrodite

The most beautiful of all the Olympian goddesses was Aphrodite, the goddess of love and beauty.

She was the ultimate symbol of the appeal and difficulty of romantic attraction. Her origins are unique, as myth says she rose from the sea foam near the island of Cyprus.

Images of this birth have been common in art and poetry for many years.

Worshipped widely across the Greek world, Aphrodite's influence extended over all matters of the heart and the arts of beauty.

Her temples, such as the one at Paphos on Cyprus, served as major centers of worship where ceremonies honoured her special qualities.

In these sacred spaces, followers sought her favor to bless their romantic endeavors or to petition for her aid in conflicts born of passion and jealousy.

Aphrodite was said to wear a magical girdle (or cestus), which had the power to inspire desire.

In some stories, she used it to influence the gods of Olympus and people on Earth, causing even the most disciplined to fall under her spell.

Particularly during the events leading to the Trojan War, she demonstrated that love could be a catalyst for both creation and destruction.

10. Hephaestus

In some myths, Aphrodite was married to Hephaestus, the god of fire and craftsmanship.

He was revered in ancient Greece for his ability to forge weapons, jewellery, and other items of divine and mortal utility.

He had been exiled from Mount Olympus because of his apparent physical imperfections and then landed on the island of Lemnos, where he established his forge.

He made many legendary creations, such as the armour of Achilles and the necklace of Harmonia, which were known for their beauty and power.

In later traditions, his workshops were believed to be located beneath volcanoes. The fires and smoke that rose from these places were seen as evidence of his work.

Here, Hephaestus toiled with the help of the Cyclopes, his assistants in metalwork.

Among his many feats of engineering was the creation of automatons, mechanical servants that performed tasks around his forge and palace.

However, his marriage to Aphrodite, albeit troubled by her constant attempts to seduce others, showed the difference and sometimes the clash between physical form and beauty.

11. Hermes

He was the god of trade, thieves, and travel, and was celebrated for his cunning and agility.

Known primarily as the ‘messenger of the gods’, his role was important for the connection between Olympus and the mortal world.

He facilitated the exchange of goods and ideas, ensuring the flow of commerce among the cities of Greece.

His winged sandals symbolised his swiftness. He also had a reputation as the protector of travellers and the patron of thieves, which may seem contradictory, a seemingly contradictory role that highlighted his control over borders and changes.

Shrines dedicated to Hermes were common in places like Cyllene in Arcadia, where he was born. These were often located at crossroads and borders.

Here, travellers would offer prayers for safe passage and merchants would seek blessings for prosperity.

Additionally, Hermes played a significant role in guiding souls to the underworld.

His ability to move between the worlds of the living and the dead, easily and with authority, further showed his role as a go-between.

His task was to lead the newly deceased to the banks of the River Styx so they could begin their journey into the afterlife.

12. Dionysus

The most wild of the Olympian gods was Dionysus. He was the god of wine, pleasure, and festivity, who brought joy and liberation to his followers through the special effects of wine and the joy of dance and song.

He was known for introducing the art of viticulture. His followers, the Maenads and Satyrs, roamed the forests in frenzied revelry, illustrating the wild, uncontrolled aspects of his worship.

Celebrations in his honour, such as the Dionysia, promoted the consumption of wine and also fostered the development of Greek theatre.

Playwrights like Sophocles and Euripides took part in these events. Their plays explored the challenges of human and divine interactions.

Moreover, Dionysus was also seen as a deity who liberated his adherents from societal norms and personal inhibitions.

As a result, his cult provided a space where the rigid structures of Greek society could be momentarily dissolved.

These places inspired strong spiritual feeling, and their rituals provided deep emotional and mental relief.

13. Hestia (who is sometimes included instead of Dionysus)

Last but not least is Hestia, the serene goddess of the hearth and home. Similar to Hera, she was the goddess of domestic life, where the hearth was a gathering spot for families and a sacred space for communal offerings.

Her presence was essential in every home; a flame in her honour was kept perpetually burning in them.

Public hearths were considered her official sanctuaries. This was especially true for those in city centres such as the prytaneion, where city officials met and the state hearth stood.

Here, Hestia's flame symbolised the unity and continuity of the community. By ensuring that this flame never went out, the Greeks expressed their respect and reverence for her as a guardian of order and domestic harmony.

She doesn’t appear in many Greek stories, but her quiet presence was known through rituals of hospitality and everyday practices of cooking and warmth.

Through these acts, she provided emotional and spiritual comfort rather than only physical warmth.

Why we still obsess about them today

The Olympian gods have continued to influence many parts of Western culture, lasting far beyond the ancient temples once dedicated to their worship.

As early as the Renaissance, artists and scholars in Europe revisited ancient Greek myths, drawing inspiration for their own works.

The resurgence of interest in classical education during this period, driven by the founding of universities and the spread of printed works, brought Greek mythology back to the cultural forefront.

By the 17th and 18th centuries, the Enlightenment further propelled the study of the Olympians as symbols of humanistic values and philosophical inquiries.

At this time, people reinterpreted figures like Zeus and Athena through reason and morality, Artists often used them in symbolic works to show different types of authority and moral ideas.

For instance, the depiction of Zeus in neoclassical art showed ideas about justice and leadership, aligning with contemporary debates about authority and the nature of power.

They still influence modern times and appear in everything from literary themes to entertainment mediums such as film and video games.

Significant cultural events, like the revival of the Olympic Games in 1896, showed the lasting appeal of the ancient Greeks, including their pantheon of gods.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.