Why America's planned invasion of Japan during WWII would have been an unmitigated disaster

As autumn approached in 1945, the prospect that troops would step ashore on Japan’s main islands loomed as the Allies’ most urgent and perilous mission.

Planners had examined casualty figures from Iwo Jima and Okinawa and concluded that only a two-phased landing on Kyushu and then Honshu could break Japan’s will to resist.

Yet preparatory estimates warned of up to four million Allied casualties, a price never before considered in modern warfare.

Planning and expected losses

In 1945 America planned an invasion of Japan under the codename Operation Downfall, which military leaders divided into two major campaigns.

For the first phase, Operation Olympic was scheduled for November 1945 and aimed to capture Kyushu, the southernmost of Japan’s main islands.

After that, Operation Coronet was set to follow in March 1946 with a landing on Honshu that targeted the Kanto Plain near Tokyo.

Planners expected to commit millions of troops across both operations, with Olympic projected to use about 767,000 soldiers and Coronet requiring over a million alone.

Naval planners prepared to use about forty‑two aircraft carriers, two dozen battleships, and hundreds of destroyers and landing craft to support the landings.

Senior officials believed that Japan would never surrender unless its home islands were invaded and occupied.

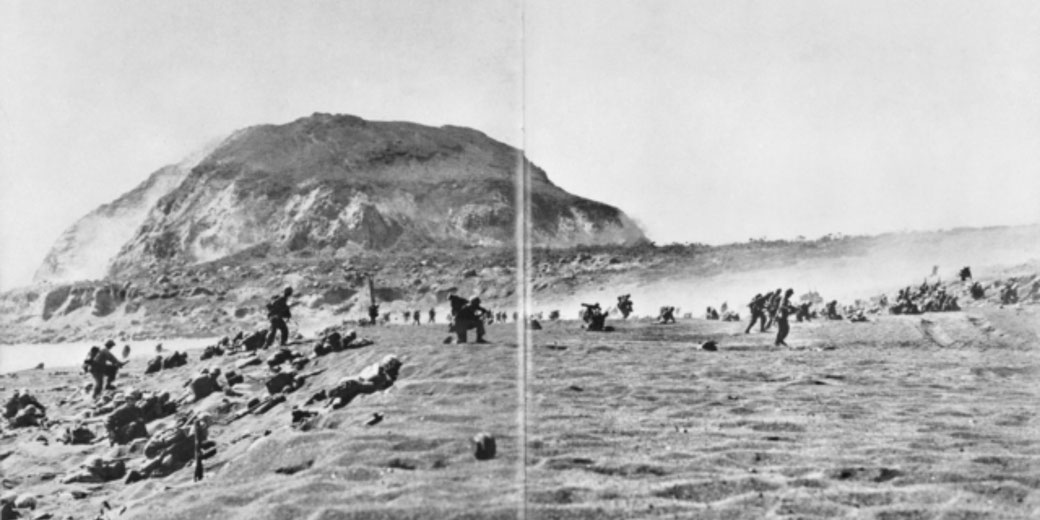

From the experiences of Iwo Jima and Okinawa, military leaders learned about the high casualty rates on both sides.

At Iwo Jima, the Americans had lost about 6,800 dead and 19,000 wounded, and at Okinawa, over 12,500 dead and 49,000 wounded.

By mid‑1945 Japan still had more than two million soldiers stationed in the home islands.

Across likely landing zones, those troops had built a dense network of bunkers, tunnels, and artillery positions.

In preparation for an invasion, the government had even formed a civilian militia called the Volunteer Fighting Corps, which included men aged fifteen to sixty and women aged seventeen to forty.

Intelligence officers estimated that up to 28 million civilians could be mobilised, even though only a fraction had been recruited and armed by the time of surrender.

In the months before the planned invasion, many civilians had received basic training with weapons such as bamboo spears, grenades, and improvised explosives.

According to intelligence reports, Japan could field over 10,000 aircraft for suicide missions against Allied ships.

Why planners started having second thoughts

As planning advanced, American officials predicted catastrophic losses in any attempt to invade, and casualty estimates for the Allies ranged from several hundred thousand to well over a million dead and wounded.

Later studies warned that total American casualties, including wounded, could reach between 1.7 million and 4 million.

In reports to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, analysts explained that the Japanese military intended to sacrifice as many lives as necessary to delay an Allied victory.

Along with large infantry and artillery fire, defenders prepared to use kamikaze aircraft, suicide boats, human torpedoes, and submarines to strike Allied fleets near the invasion beaches.

Some intelligence officers also warned that the Japanese Army possessed poison gas and biological weapons, produced by units such as Unit 731, although evidence of operational plans to deploy them remained limited.

On Kyushu alone, more than 900,000 soldiers were expected to be concentrated by late 1945.

They fortified coastal areas and inland defensive lines, and military engineers created hundreds of miles of tunnels, bunkers, and concealed firing positions to cause the most casualties.

At the same time, civilians were mobilised to construct traps and obstacles, and propaganda campaigns reinforced a willingness to fight to the death.

Thanks to a series of intercepted messages, American intelligence learned of a final defence plan known as Ketsu‑Go.

Under that plan, Japanese forces intended to inflict unsustainable casualties on the Allies in the first weeks of the invasion to force negotiations on terms short of unconditional surrender.

How Japan was preparing for the invasion

During the fighting at Okinawa, naval forces had already faced the damaging power of kamikaze tactics, and Japanese pilots had flown nearly 1,900 suicide missions in that single campaign.

As a result of those attacks, dozens of ships were sunk and hundreds were damaged.

With thousands of aircraft that were hidden in caves and that were dispersed across airfields, Japan had the ability to launch repeated attacks against invasion fleets.

According to military analysts, losses among transports, landing craft, and carriers would be so severe that resupply of troops on the beaches could collapse.

Without air superiority, the very large supply effort needed to maintain millions of soldiers on hostile islands would likely fail.

For the Japanese population, the consequences of an invasion would have been catastrophic.

By 1945 Allied bombing had already destroyed much of Japan’s urban infrastructure, and a ground invasion would have intensified the suffering of civilians caught between well dug-in defenders and advancing troops.

In cities such as Tokyo and Kyoto, expected street fighting would have killed hundreds of thousands of men, women, and children who had been conscripted or coerced into service as part of the Volunteer Fighting Corps.

Starvation and disease were already widespread due to the blockade, and the added disruption of an invasion could have killed millions more.

What the US chose to do instead of invading

Based upon all of these factors, in Washington, American leaders debated alternatives to a direct invasion.

Figures such as Secretary of War Henry Stimson, Admiral Ernest King, and General Douglas MacArthur presented different views on whether an invasion or continued blockade was the best course.

Through the summer of 1945, they considered a continued blockade and strategic bombing, which had already severely damaged Japan’s economy and infrastructure.

After the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 and the Soviet invasion of Manchuria, Japan announced its surrender on 15 August, and the war ended without the catastrophic losses that Operation Downfall would have produced.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.