The last days Adolf Hitler and the controversial stories of his death

On April 30, 1945, as the final sounds of World War II echoing through the bomb-shattered streets of Berlin, Adolf Hitler, the infamous leader of Nazi Germany, met his end.

Hidden deep within the bowels of the Fuhrerbunker, a subterranean fortress, Hitler's final act closed a dark chapter in human history.

But, what do we know about what happened within those bleak, concrete walls?

Is there a chance that Hitler secretly escaped?

And what can the forensic and historical evidence tell us about the truth behind the dictator's death?

Hitler's desperate situation

As the Second World War neared its tumultuous conclusion, Adolf Hitler, once the unchallenged leader of Nazi Germany, faced his final days in a rapidly diminishing realm of power and influence.

By April 1945, the Allies had significantly weakened the German military, and Soviet forces were closing in on Berlin.

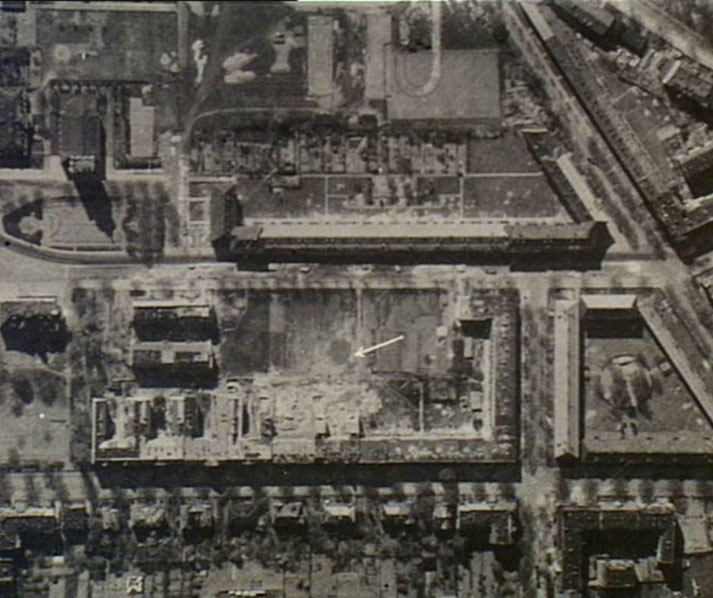

Amidst this backdrop, Hitler, along with a group of loyalists and officials, retreated to the Fuhrerbunker, a bunker complex beneath the Reich Chancellery in Berlin.

What was the Fuhrerbunker?

Constructed in two phases, with the first part completed in 1936 and the second, deeper section added in 1944, this subterranean fortress was designed to withstand the most severe bombings.

By April 1945, as the Allies closed in on Berlin, it became the epicenter of the Nazi regime's final chapter.

This bunker, with its air filtration system, walls up to 3.5 meters thick, and self-sufficient utilities, was a marvel of wartime engineering.

It consisted of approximately 30 small rooms, including Hitler's private quarters, conference rooms, and accommodations for staff and high-ranking officials.

Despite its fortifications, the bunker's atmosphere was claustrophobic, with low ceilings and narrow corridors.

The electric lights, necessary due to the lack of natural light, cast a harsh glow over its inhabitants, contributing to a pervasive sense of doom.

Who was in the Fuhrerbunker with Hitler?

As Adolf Hitler faced the inevitable collapse of the Third Reich, a select group of loyalists, officials, and personal staff accompanied him into the Fuhrerbunker.

This group comprised individuals who were either fiercely loyal to Hitler or who had nowhere else to turn as the Allies closed in on Berlin in April 1945.

Among the key figures who joined Hitler in the bunker was Eva Braun, his long-time companion, who had been a part of Hitler's private life for many years but had largely remained out of the public eye.

Braun's decision to stay with Hitler until the end was a testament to her loyalty to him.

Joseph Goebbels, the Reich Minister of Propaganda, was another prominent Nazi official in the bunker.

A fanatical supporter of Hitler, Goebbels was accompanied by his wife, Magda, and their six children.

Martin Bormann, Hitler's private secretary and head of the Party Chancellery, was also present.

Bormann was a powerful figure within the Nazi hierarchy and one of Hitler's closest confidants.

His presence in the bunker was indicative of his unwavering allegiance to Hitler.

Several military officers were also in the bunker, including General Wilhelm Burgdorf, General Hans Krebs, and SS-Brigadeführer Wilhelm Mohnke.

These men were responsible for various military aspects of the bunker's operation and defense of Berlin.

Other notable figures included Otto Günsche, Hitler's personal adjutant, and Heinz Linge, his valet.

Traudl Junge, one of Hitler's secretaries, was also present; she later provided detailed accounts of the final days in the bunker.

Rochus Misch, who served as a courier and telephone operator, provided additional eyewitness accounts of the atmosphere and events inside the bunker.

What was life like in the bunker?

As the sound of artillery grew louder each day, those inside lived in an increasingly isolated world.

Officers and staff tried to maintain a semblance of normalcy, with daily briefings and meals, but the reality of the impending defeat of the Third Reich was inescapable.

Despair was palpable among its occupants, many of whom would choose suicide in the bunker or shortly after leaving it.

Hitler's presence dominated the bunker. His daily routines, already unusual, became increasingly erratic as he grappled with the inevitability of defeat.

Meetings with generals and advisors often turned to delusional planning for a counter-offensive that would never materialize.

In contrast, Eva Braun, Hitler's companion, tried to maintain a cheerful demeanor, hosting small gatherings and maintaining her daily routines, even as the situation outside deteriorated.

The dramatic decline in Hitler's mental state

By April 22, following a briefing that revealed the encirclement of Berlin was complete and no military relief was in sight, Hitler suffered a complete emotional breakdown.

He acknowledged for the first time that the war was truly lost, and spoke openly of suicide.

In these last days, his health visibly deteriorated; he exhibited symptoms of Parkinson's disease, and his mental state was unstable.

April 28 brought another blow to Hitler's crumbling regime. News arrived that Benito Mussolini, the Fascist leader of Italy and Hitler's ally, had been executed by Italian partisans.

This event profoundly impacted Hitler, reinforcing his resolve not to be captured alive.

On April 29, as Soviet forces fought within a few blocks of the Chancellery, Hitler married his long-time companion Eva Braun in a brief midnight ceremony in the bunker.

Immediately after, he dictated his last will and testament, a document filled with defiance and delusion.

On April 30, with the Red Army less than 500 meters from the bunker, Hitler and Braun retired to a private room.

Sometime in the afternoon, they committed suicide—Hitler by a gunshot to his head and Braun by ingesting cyanide.

Their bodies were carried outside, doused in petrol, and set on fire, as per Hitler's instructions to prevent his remains from being paraded by the victors.

Did Hitler secretly escape the bunker?

While the predominant and widely accepted account is that Hitler committed suicide in his bunker on April 30, 1945, alternative theories have persisted over the years, fueling controversies and debates among historians and conspiracy theorists alike.

One of the most persistent alternative theories suggests that Hitler did not die in the bunker but instead escaped to South America, particularly Argentina, where a substantial German community existed.

Proponents of this theory argue that the lack of definitive forensic evidence and the chaos surrounding the fall of Berlin provided an opportunity for escape.

Despite its popularity in popular media, this theory lacks substantial evidence and is generally dismissed by mainstream historians.

Another theory posits that the bodies found and identified as Hitler and Eva Braun were actually doubles, used as decoys to facilitate their escape.

This theory also hinges on the assertion of inadequate forensic analysis, suggesting that the Soviets, who recovered the bodies, either deliberately propagated misinformation or made errors in their identification process.

However, this theory is undermined by testimonies from those inside the bunker, who confirmed Hitler's and Braun's deaths, as well as subsequent forensic analyses.

The controversy was further fueled by the Soviet Union's initial secrecy and later contradictory statements about Hitler's death.

For a time, the Soviets neither confirmed nor denied Hitler's suicide, leading to speculation about his fate. It was not until years later that they publicly stated Hitler had died by suicide in the bunker.

Who were the eyewitnesses of Hitler's death?

Among the most notable eyewitnesses were Traudl Junge, Hitler's personal secretary; Otto Günsche, Hitler's SS adjutant; Heinz Linge, his valet; and Rochus Misch, a telephonist and courier.

Their accounts, given post-war, offer a harrowing glimpse into the bunker's claustrophobic world as the Third Reich crumbled.

Traudl Junge, who had worked for Hitler since 1942, provided detailed descriptions of the atmosphere within the bunker.

She recounted the daily routines and the palpable sense of despair as the Red Army encircled Berlin.

Junge described Hitler's mood swings, his decline in physical and mental health, and the strange normalcy that some tried to maintain, even as the end neared.

She was also a witness to Hitler's marriage to Eva Braun and was tasked with transcribing his last will and political testament.

Otto Günsche, who was responsible for guarding Hitler, offered insights into the Führer's final decisions and his state of mind.

Günsche was one of the last people to see Hitler and Braun alive before their suicides and was involved in the subsequent handling of their bodies, as per Hitler's instructions.

His testimony helped corroborate the method and timing of Hitler's death.

Heinz Linge, who served as Hitler's valet, provided a unique perspective on the personal aspects of Hitler's life during those last days.

Linge was responsible for maintaining Hitler's daily routine and was among those who first discovered the bodies of Hitler and Braun.

His account detailed the grim and chaotic aftermath within the bunker following their suicides.

Rochus Misch, who operated the telephones and served as a courier, offered a different angle, focusing on the communications and the mood among the staff.

Misch described the bunker as a place of uncertainty, fear, and resignation, witnessing the final breakdown of the Nazi hierarchy.

What the forensic evidence found

In the immediate aftermath of the war, the Allied forces, particularly the Soviets who had captured Berlin, were primarily responsible for investigating Hitler's death.

Their findings, along with later analyses, have played a significant role in piecing together the final moments of the Nazi leader.

Initially, the Soviet authorities were secretive about the details they uncovered.

It was only in the years following the war that they released information about the findings in the Fuhrerbunker.

The Soviets claimed to have found the partially burned remains of Hitler and Eva Braun near the bunker.

These remains were said to include a fragment of a skull with a gunshot wound and a fragment of a jaw, identified as Hitler's through dental records provided by his personal dentist, Hugo Blaschke, and his assistant.

This dental evidence became a cornerstone in confirming Hitler's identity, as the dental work matched records and descriptions provided by those who knew him.

In 2009, a study conducted by American researchers on the skull fragment held by the Russians revealed that it likely belonged to a woman under 40, not Hitler.

This revelation cast doubt on some aspects of the earlier Soviet findings but did not discount other evidence supporting Hitler's suicide.

Additionally, there were reports of the Soviets conducting autopsies on the supposed remains of Hitler and Braun, though detailed results of these autopsies were not widely disseminated and the remains were reportedly later destroyed.

This lack of transparency and the eventual destruction of physical evidence have been sources of skepticism and conspiracy theories.

Despite the questions raised by the 2009 study, the convergence of other forensic evidence, particularly the dental records, and eyewitness accounts have led most historians to continue to accept the conclusion that Hitler died by suicide in the bunker.

The dental records were extensively cross-examined with the accounts of his dentist and assistants, who were captured by the Americans and provided detailed descriptions of Hitler's dental work.

How the world reacted to news of Hitler's death

Hitler's suicide in the Fuhrerbunker occurred against the backdrop of the Battle of Berlin, one of the war's final and most brutal conflicts.

Just a week later, on May 7, 1945, Germany offered an unconditional surrender, effectively ending the war in Europe, a formal declaration of which was made on May 8, 1945, known as Victory in Europe (VE) Day.

The news of Hitler's death was met with a mix of reactions around the world.

For the Allies and those who had suffered under Nazi occupation, it was a moment of deep relief and a signal that the war's end was near.

Among the German populace and Nazi loyalists, it marked the definitive collapse of the regime they had followed, often with fanatical devotion.

In the immediate aftermath, there was chaos and a power vacuum in Germany, leading to internal struggles among Nazi officials and commanders.

Hitler's death paved the way for the Potsdam Conference in July-August 1945, where the leaders of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union made crucial decisions about the post-war order, the division of Germany, and the onset of the Cold War dynamics that would define global politics for decades.

Furthermore, the end of the war did not immediately alleviate the suffering of millions in Europe.

The continent was left ravaged by years of conflict, with countless cities in ruins, economies destroyed, and populations displaced.

The task of rebuilding was immense and led to significant political and social changes, including the establishment of the United Nations in October 1945 and the initiation of the Marshall Plan in 1948 to rebuild European economies.

In Germany, Hitler's death marked the beginning of a long process of denazification and coming to terms with the horrors of the Holocaust and the war.

The Nuremberg Trials, which began in November 1945, were a crucial step in holding leading Nazis accountable for war crimes and crimes against humanity.

These trials were seminal in the establishment of international law and the principle of accountability for such crimes.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.