What was the Cold War's influence on modern American foreign policy?

The Cold War transformed the priorities and methods of American foreign policy during a long period of international rivalry between the United States and the USSR, which stretched from the end of the Second World War in 1945 to the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

It produced policies, institutions, and military alliances that continue to guide Washington’s actions in global affairs.

Rather than operating purely through diplomacy or commerce, the United States increasingly relied on military involvement that reinforced containment through strategic alliances to manage threats and assert its interests on a global scale.

What was the 'Cold War'?

The Cold War emerged in the immediate aftermath of World War II and developed from growing mistrust between the United States and the Soviet Union.

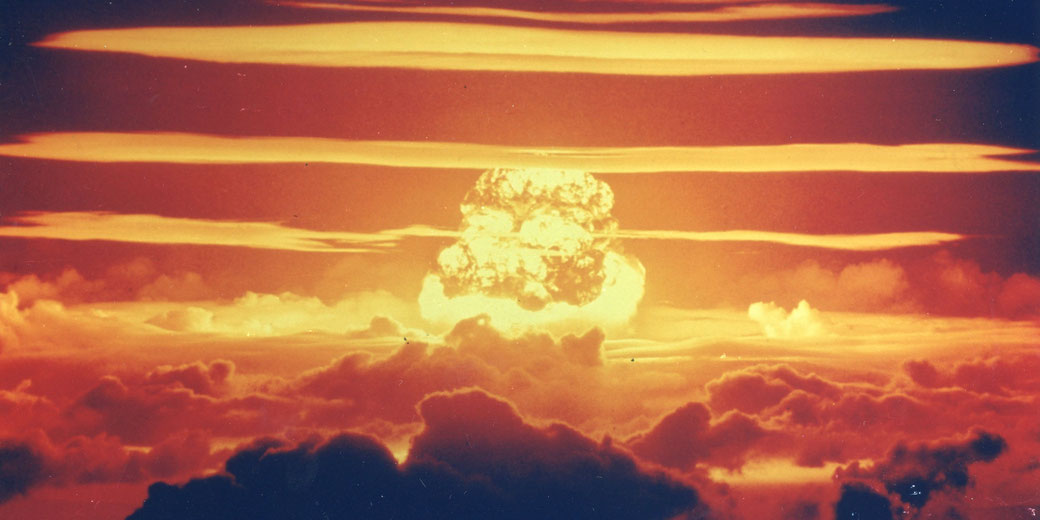

Their ideological opposition, capitalist democracy versus state socialism, resulted in a decades-long power struggle played out through espionage, proxy wars, economic competition, and arms races.

Events such as the Berlin Blockade (1948–1949), the Korean War (1950–1953), and the Cuban Missile Crisis (1962) illustrated the extent to which both powers viewed each other as serious threats, even in the absence of direct military confrontation.

By the 1970s, efforts such as détente attempted to ease Cold War tensions, but the rivalry endured.

The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 reignited hostilities, and it led to a renewed American commitment to military buildup under Ronald Reagan’s administration.

Meanwhile, diplomatic talks over nuclear weapons, such as the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) and the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START), defined the boundaries of cooperation and competition.

SALT I was signed in 1972, while START I came much later, in July 1991, just months before the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

What was America's foreign policy during the Cold War?

Throughout the Cold War, the United States prioritised the policy of containment, first articulated in George Kennan’s 1947 “Long Telegram” and later formalised through the Truman Doctrine.

This approach committed the U.S. to halting the spread of communism, particularly in regions deemed strategically significant.

In practice, this led to extensive military and economic involvement in countries as varied as Greece, Iran, Vietnam, and Nicaragua.

Foreign aid was often tied to political allegiance, with programmes like the Marshall Plan, which funded European recovery and cemented loyalty to the Western bloc.

Under the Eisenhower Doctrine, Kennedy’s Alliance for Progress, and Johnson’s escalation in Vietnam, American foreign policy became heavily interventionist.

Successive administrations backed authoritarian regimes, funded paramilitary groups, and deployed troops in the name of fighting communism.

The establishment of the CIA and National Security Council created covert operations, while the creation of NATO in 1949 and the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO), which was signed in September 1954 and came into force in February 1955, demonstrated the commitment to joint defence.

The Cold War mindset firmly established the belief that international stability required American leadership, often enforced through military or economic pressure.

The legacy of Cold War diplomatic failures

The Vietnam War exposed the limits of American interventionism. Initiated under the premise of containing communism in Southeast Asia, it escalated into a prolonged and costly conflict.

By the time U.S. combat troops withdrew in March 1973 and with the eventual fall of Saigon in April 1975, the war had severely damaged American credibility abroad and shaken domestic confidence in foreign policy decision-making.

The idea that military power alone could guarantee geopolitical outcomes proved unsustainable.

In Latin America, American support for coups and right-wing regimes produced long-term instability and widespread resentment.

The 1954 coup in Guatemala, the backing of the Pinochet regime in Chile, and the Iran-Contra affair under Reagan, which unfolded from 1985 and became public in 1986, illustrated the unintended consequences of prioritising anti-communism above democratic values.

These policies contributed to distrust of American motives, particularly in the Global South, where U.S. involvement often undermined the very institutions it claimed to support.

Important diplomatic tensions since the Cold War

Following the Cold War, U.S. foreign policy shifted toward a unipolar strategy focused on global leadership and the promotion of liberal democracy.

However, many Cold War habits persisted. NATO expansion in Eastern Europe during the 1990s triggered renewed tensions with Russia, culminating in conflicts such as the 2008 Georgia war and the annexation of Crimea in 2014.

The 1999 bombing of Serbia and later interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan showed a continued reliance on military solutions, often without stable long-term outcomes.

New rivalries also emerged. The rise of China, particularly after its admission to the World Trade Organization in December 2001, prompted strategic competition in trade and technology.

It reshaped regional influence. While tensions grew gradually, the 2010s marked a turning point in U.S.-China rivalry, especially under the Obama and Trump administrations.

American naval activity in the South China Sea, arms sales to Taiwan, and disputes over semiconductors and artificial intelligence technology have drawn attention back to Asia as a critical arena of foreign policy.

These confrontations show clear echoes of Cold War logic, as Washington once again focuses on confronting authoritarian rivals through economic pressure and alliance-building.

What does the future hold for US relations?

Given the reappearance of multipolar competition, the United States is now navigating a foreign policy situation that blends Cold War strategies with contemporary concerns.

The formation of new coalitions, such as AUKUS with Australia and the United Kingdom, reflects ongoing efforts to counter perceived threats in the Indo-Pacific.

Climate change introduced a new dimension to international diplomacy, and cyber warfare added further complexity.

The global spread of misinformation required cooperation, even with geopolitical rivals.

In the coming decades, America’s ability to balance competition with engagement will be critical.

Rather than relying solely on deterrence and containment, future policy may need to focus on diplomacy, multilateral agreements, and long-term stability.

The impact of the Cold War still informs the language and instincts of American foreign policy, but evolving challenges will test whether that legacy can be adapted or must be replaced.

The success or failure of this adaptation will determine the character of U.S. global leadership in the twenty-first century.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.