When hell came to Nagasaki: The atomic cataclysm that brought WWII to an end

On 9 August 1945, the city of Nagasaki experienced destruction on a scale never before seen in human history. In a single instant an atomic bomb unleashed fire and heat upon the city, killing tens of thousands and leaving survivors with horrific injuries.

The attack came only three days after the bombing of Hiroshima, and it pushed Japan closer to unconditional surrender and brought the Second World War to its conclusion.

The secret development of atomic weapons

In 1939, the Manhattan Project began after scientists warned President Franklin D. Roosevelt that Nazi Germany might be working on its own atomic bomb.

Over time the project expanded to involve more than 130,000 people across many secret sites in the United States and cost about $2 billion.

At Los Alamos in New Mexico, Oak Ridge in Tennessee, and Hanford in Washington, workers and scientists completed different stages of uranium enrichment and plutonium production.

Within Los Alamos, J. Robert Oppenheimer led a team that included notable physicists such as Enrico Fermi and Niels Bohr, while General Leslie Groves oversaw the military side of the project.

They designed two types of atomic bombs. The first, called “Little Boy,” used enriched uranium, and the second, “Fat Man,” relied on a plutonium implosion mechanism.

By 16 July 1945, the scientists had completed their work and successfully tested a plutonium bomb at the Trinity site in New Mexico.

From the fireball’s enormous power, it became clear that the new weapon could destroy entire cities.

In the following weeks, American military planners prepared to use the bombs on Japan to force its surrender without a costly invasion of the home islands.

After he consulted with senior advisers, President Harry S. Truman authorised their use.

Many believed that the bombs would save hundreds of thousands of American and Japanese lives by avoiding a drawn‑out conflict.

The crucial events leading up to Nagasaki

After the bombing of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945, at least 70,000 people died instantly, and many more perished in the weeks that followed from burns and radiation sickness.

Inside Japan, leaders were hesitant to surrender. Members of the Supreme Council for the Direction of the War debated whether to fight on, and some military officials insisted that Japan could still inflict heavy casualties if the Allies invaded.

Then, on 8 August, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan and launched Operation August Storm, a massive invasion of Japanese‑held Manchuria with over a million troops, which created a new crisis for Tokyo.

In the days that followed, American commanders prepared to use a second bomb to force Japan to accept unconditional surrender.

The Day of the Bombing: August 9, 1945

On the morning of 9 August, the American B-29 bomber Bockscar, commanded by Major Charles W. Sweeney and crewed by twelve men, approached Kokura but failed to locate the city due to cloud and smoke from earlier raids.

After they abandoned the primary target, the crew turned towards Nagasaki, which also had partial cloud cover but still offered a bombing window.

At 11:02 a.m., the crew released the “Fat Man” bomb, which weighed about 10,300 pounds, contained 6.4 kilograms of plutonium, and had an explosive yield of around 21 kilotons.

Above the Urakami Valley, the bomb detonated about 500 metres in the air. In an instant, a blinding flash lit the sky, followed by a massive fireball and shockwave that flattened buildings within a two-kilometre radius.

Close to the hypocentre, temperatures soared to thousands of degrees Celsius.

People and structures near the explosion were incinerated instantly. Further from the centre, victims suffered burns, broken bones, and radiation exposure as fires spread across the city.

The utter devastation caused

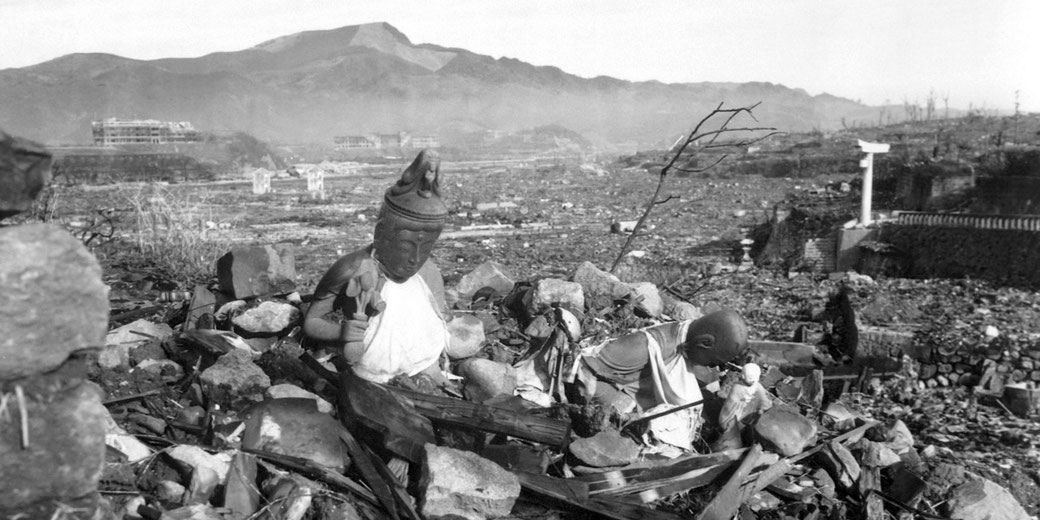

Within Nagasaki’s surrounding hills, the confined blast intensified the destruction in the valley.

Entire districts, including Urakami, were destroyed, and the former large Urakami Cathedral, the largest Christian church in Asia, was reduced to rubble.

Historians estimate that between 35,000 and 40,000 people died immediately. By the end of 1945 the death toll had risen to between 60,000 and 80,000 as injuries and radiation sickness claimed more lives.

Across the city, entire families disappeared, and shadows of bodies were etched onto walls by the intense heat.

As hospitals collapsed, doctors and nurses were also killed. Survivors searched for loved ones in ruins, and they experienced unimaginable suffering.

In the weeks and months after the bombing, radiation exposure caused severe illnesses.

Many survivors experienced burns, hair loss, and internal bleeding. Children who had been exposed in the womb later suffered birth defects and developmental issues.

Because infrastructure had been destroyed, food, clean water, and medical supplies were scarce.

With Nagasaki’s industrial facilities obliterated, production stopped and tens of thousands were left without shelter or employment.

The global reaction to news of the bombing

Around the world, news of the second atomic bombing spread quickly. President Truman announced that America had used another atomic bomb against Japan and warned that further attacks would follow if Japan refused to surrender.

At the same time, some scientists who had worked on the Manhattan Project expressed regret over the use of the bomb and questioned the morality of targeting civilians.

In response to the bomb’s destructive power, the Soviet Union sped up its own atomic programme, which led to its first successful test in 1949.

Leaders in Moscow recognised that nuclear weapons would define future warfare.

In Japan, Emperor Hirohito intervened to end the stalemate among his advisers and urged acceptance of the Allied surrender terms.

On 15 August 1945, his surrender speech, known as the Gyokuon-hoso, was broadcast to the nation, and on 2 September 1945, Japan formally surrendered aboard USS Missouri.

As a result of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the world saw the terrifying power of nuclear weapons, and global history entered a new era.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.