When hell came to Nagasaki: The atomic cataclysm that brought WWII to an end

On 9 August 1945, the city of Nagasaki experienced destruction on a scale never before seen in human history. In a single instant an atomic bomb unleashed fire and heat upon the city, killing tens of thousands and leaving survivors with horrific injuries.

The attack came only three days after the bombing of Hiroshima, and it pushed Japan closer to unconditional surrender and brought the Second World War to its conclusion.

The secret development of atomic weapons

In 1939, the Manhattan Project began after scientists warned President Franklin D. Roosevelt that Nazi Germany might be working on its own atomic bomb.

Over time the project expanded to involve more than 130,000 people across many secret sites in the United States and cost about $2 billion.

At Los Alamos in New Mexico, Oak Ridge in Tennessee, and Hanford in Washington, workers and scientists completed different stages of uranium enrichment and plutonium production.

Within Los Alamos, J. Robert Oppenheimer led a team that included notable physicists such as Enrico Fermi and Niels Bohr, while General Leslie Groves oversaw the military side of the project.

They designed two types of atomic bombs. The first, called “Little Boy,” used enriched uranium, and the second, “Fat Man,” relied on a plutonium implosion mechanism.

By 16 July 1945, the scientists had completed their work and successfully tested a plutonium bomb at the Trinity site in New Mexico.

From the fireball’s enormous power, it became clear that the new weapon could destroy entire cities.

In the following weeks, American military planners prepared to use the bombs on Japan to force its surrender without a costly invasion of the home islands.

After he consulted with senior advisers, President Harry S. Truman authorised their use.

Many believed that the bombs would save hundreds of thousands of American and Japanese lives by avoiding a drawn‑out conflict.

However, the Japanese government, under the leadership of Prime Minister Kantaro Suzuki, decided to ignore the Allies' ultimatum, a decision often translated as a policy of 'silent contempt.'

This rejection, coupled with the desire to hasten the end of the war and avoid more American casualties, was instrumental in the fateful decision to employ nuclear weaponry.

The crucial events leading up to Nagasaki

Following the Potsdam Declaration and the refusal of the Japanese government to surrender, the United States moved forward with Operation Downfall, a plan for the invasion of Japan.

However, there were fears among Allied leadership that such an invasion would result in heavy casualties, with some estimates running into the millions.

Thus, the decision was made to employ the new atomic weapons developed by the Manhattan Project.

The hope was that such a demonstration of destructive power would force Japan into submission, ending the war swiftly and minimizing further loss of life.

The first atomic bomb, "Little Boy," was dropped on the city of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, by the B-29 bomber Enola Gay.

The bomb detonated 600 meters above the city, creating a fireball that decimated the city center and resulted in the deaths of approximately 80,000 people instantly, with tens of thousands more dying later from the effects of radiation and injuries.

The destruction was unlike anything seen before, and the Japanese leadership was left stunned.

Despite the devastation in Hiroshima, Japan did not immediately surrender. Prime Minister Suzuki and the Japanese War Council were still debating how to respond to the Potsdam Declaration and the destruction of Hiroshima when the Allies sent another chilling message.

The next target was the city of Kokura, but due to poor visibility on August 9, the bomber Bockscar diverted to its secondary target: Nagasaki.

Nagasaki, like Hiroshima, was a vital war industry city, hosting numerous factories, industrial plants, and shipping operations.

The city was nestled in a series of narrow valleys, and the geography inadvertently amplified the destructive power of the bomb, as the blast was confined within the city's boundaries.

The Day of the Bombing: August 9, 1945

August 9, 1945, began as an ordinary day for the citizens of Nagasaki, despite the ongoing war and the news of Hiroshima's devastation three days earlier.

Nagasaki's skies were overcast, providing a deceptive sense of security, hiding the impending disaster looming in the clouds.

The responsibility for this mission was assigned to the B-29 bomber, Bockscar, piloted by Major Charles Sweeney.

The primary target for the day was the city of Kokura, but poor visibility over the city due to smoke from a previous firebombing raid on a nearby city, coupled with looming clouds, led to a change in plans.

After making three unsuccessful passes over Kokura, the decision was made to proceed to the secondary target: Nagasaki.

Despite fuel concerns and further visibility issues due to cloud cover over Nagasaki, at 11:02 a.m., the bomb "Fat Man" was released.

It exploded approximately 43 seconds later at an altitude of about 1,650 feet. The initial blast was confined by the surrounding hills and mountains, intensifying the damage inflicted on the city.

The city was engulfed in a fireball with an estimated temperature of 3,900 degrees Celsius, causing buildings and other structures to crumble as if they were made of sand.

People in the immediate vicinity were incinerated instantly, while those further away suffered severe burns and injuries from the blast wave.

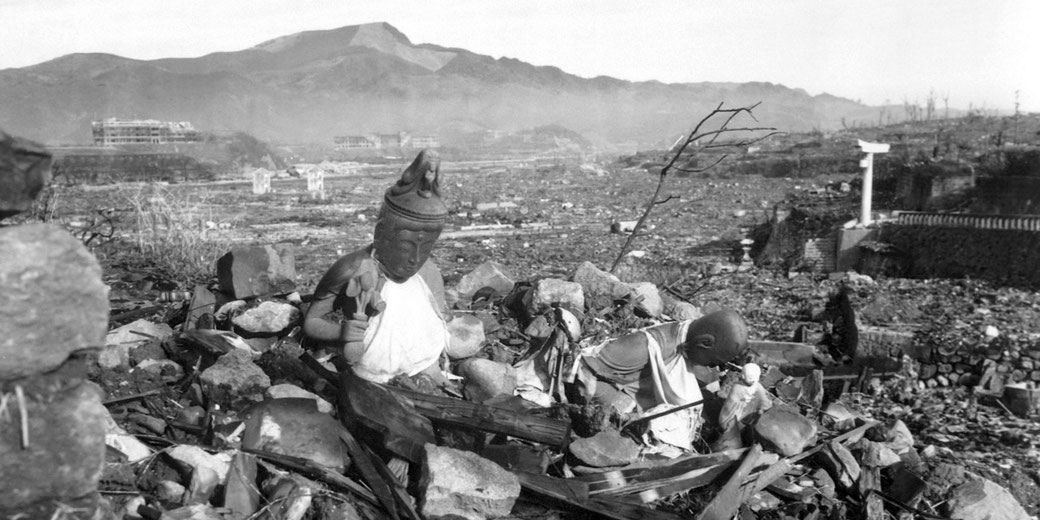

The utter devastation caused

The atomic bomb detonated over Nagasaki with a force equivalent to 21 kilotons of TNT, flattening a significant part of the city and causing devastation on an almost unimaginable scale.

The immediate aftermath of the blast was a scene of utter chaos and destruction.

The impact of the bomb decimated a large part of the city, causing widespread death and injury.

Approximately 40,000 people were killed instantly, and thousands more were severely injured.

The intense heat and the subsequent fires ignited by the explosion razed buildings, incinerated vegetation, and caused numerous secondary fires throughout the city, which added to the death toll.

Emergency services were overwhelmed. Many hospitals and clinics were destroyed or severely damaged in the blast, leaving the injured with few places to seek medical aid.

Doctors and nurses were among the casualties, exacerbating the shortage of medical personnel to deal with the massive number of casualties.

To make matters worse, no one was prepared for the nature of the injuries caused by radiation.

In the hours following the explosion, a black rain, filled with dust, soot, and nuclear fallout, began to fall over the city, causing further harm to survivors and contaminating the city's water supplies.

This radioactive fallout led to further health complications among survivors, including burns, radiation sickness, and later an increased incidence of cancer and other diseases.

The survivors, known as Hibakusha, were left to navigate a ruined city and make sense of a disaster of unprecedented proportions.

In the face of limited medical help and knowledge about radiation sickness, they suffered not only physical but also psychological trauma, grappling with the loss of loved ones, homes, and the world as they knew it.

The global reaction to news of the bombing

News of the bombing of Nagasaki, coming so soon after the similar attack on Hiroshima, sent shockwaves throughout the international community.

Responses varied greatly, from horror and disbelief at the sheer scale of destruction, to relief among the Allies that the end of the long and brutal war might finally be within reach.

In the Allied nations, initial reactions were marked by a mix of victory and awe at the power of the new weapon.

These feelings were articulated in the announcement by President Truman on the day of the Nagasaki bombing, where he warned of a "rain of ruin" should Japan not surrender.

In his statement, he framed the atomic bombings as necessary actions to hasten the end of the war and save lives.

These sentiments were echoed in newspaper headlines and public opinion across Allied countries, reflecting relief that the tide of the war had decisively turned.

However, as the magnitude of the human suffering caused by the bombings became clear, a sense of unease and moral questioning permeated many corners of society.

There was widespread shock and horror at the scale of civilian casualties, raising ethical questions about the use of such a devastating weapon.

Some scientists who worked on the Manhattan Project, such as physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, were haunted by the destructive power they had helped to unleash.

In the Soviet Union, the bombings were viewed through the lens of geopolitical strategy.

The Soviet Union declared war on Japan two days after the Hiroshima bombing and one day before Nagasaki, intending to assert its post-war presence in Asia.

The bombings, which effectively ended the war before the Soviets could significantly engage, heightened tensions between the USSR and the US, setting the stage for the Cold War.

As for Japan, the shock and horror at the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki led Emperor Hirohito to intervene in the government's decision-making process.

On August 15, six days after the Nagasaki bombing, he announced Japan's unconditional surrender, bringing World War II to an end.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.