How the secretive Sykes-Picot Agreement led to the current conflict in the Middle East

In May 1916, Britain and France secretly agreed to the Sykes-Picot Agreement, which divided large areas of the Ottoman Empire into spheres of influence in preparation for an Allied victory in World War I.

The pact favoured European imperial control over local interests, and its terms disregarded the hopes of the people who lived in the Middle East.

However, the long-term consequences of the agreement created conditions that still drive conflict in the region today.

The origins of the Sykes-Picot Agreement

During the First World War, the weakening of the Ottoman Empire created a scramble among European powers to secure influence over its territories.

The empire had ruled the Middle East for centuries, but its military failures and administrative decline left large regions vulnerable to outside intervention.

After the Ottomans formally entered the war in October 1914, when they bombarded Russian ports, their lands became an immediate target for Allied expansion.

In response, British leaders identified the Suez Canal and the oil fields of Mesopotamia as key objectives that had to be protected from potential threats and rival empires.

The early occupation of Basra in November 1914 already provided Britain with a foothold in Mesopotamia, while French leaders wanted to keep their traditional influence in the Levant and pressed claims to Syria and Lebanon.

As negotiations developed, the British also exchanged letters with Sharif Hussein of Mecca, who agreed to lead an Arab revolt against Ottoman rule in exchange for promises of independence.

The Hussein–McMahon Correspondence of 1915–1916 offered Arab sovereignty, but it was unclear about Palestine, which left room for British interpretation.

At the same time, British officials explored a different agreement with France to divide the same lands into separate zones of imperial control.

The conflicting promises created mistrust because the commitments to Hussein did not match the secret Anglo-French plan.

Who was involved in the agreement?

The two main figures were Sir Mark Sykes, a British politician with knowledge of Middle Eastern affairs, and François Georges-Picot, a French diplomat who worked to secure French influence in Syria.

Sykes had written a study of the Islamic world, Dar-ul-Islam, in 1905, which influenced his later views on Britain’s imperial approach to the region. Georges-Picot had served as French consul in Beirut and came from a prominent diplomatic family, which gave him both experience and personal ties to French aims in the Levant.

Their negotiations favoured imperial interests over the populations who lived in the region, and they excluded any Arab input despite ongoing promises of independence.

For the Russians, participation in the negotiations offered recognition of their claims to eastern Anatolia and matched their desire to expand.

Their aim to control Constantinople and the Straits had been addressed separately in the Constantinople Agreement of 1915.

Italian involvement followed later, with treaties promising spheres of influence in Anatolia, though those claims were far less successful in practice.

From the perspective of Arab leaders, the exclusion from these talks made clear that their sacrifices in the Arab Revolt would not be rewarded with sovereignty once the war ended.

What were the terms of the agreement?

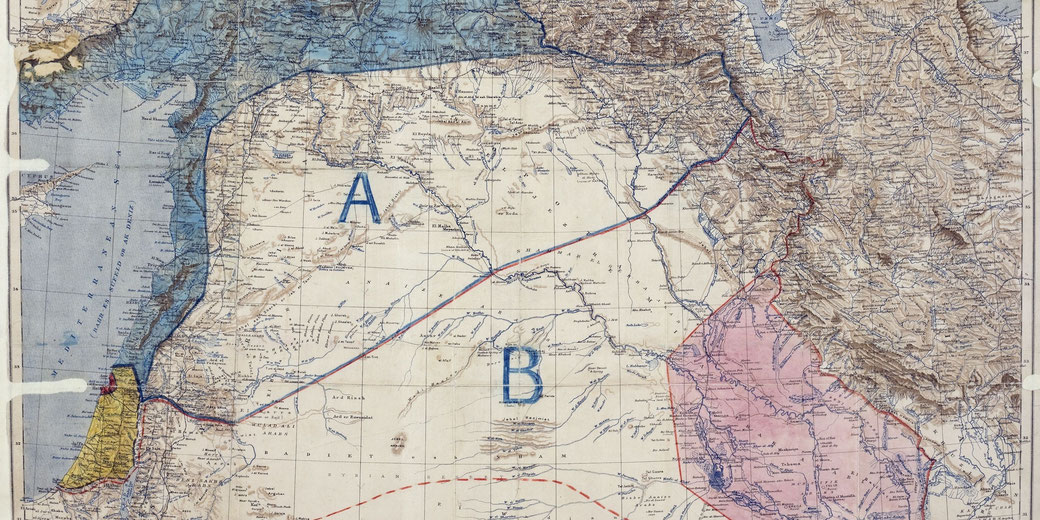

Under the terms of Sykes-Picot, the Middle East was divided into zones of direct and indirect European control.

France’s “blue zone” included Cilicia, Lebanon, and coastal Syria, with indirect influence over inland northern Syria.

Mosul was initially placed in the French sphere, but after oil was discovered, Britain argued successfully that Mosul should be in their mandate after the war.

Britain’s “red zone” included southern Mesopotamia, with Basra and Baghdad, and reached toward the Persian Gulf and Arabia.

Palestine, regarded as too important to be given exclusively to either power, was placed in the "brown zone" for international administration under an unclear plan that satisfied no one.

In effect, the “blue zone” under French authority and the “red zone” under British authority formed the basis for the later League of Nations mandates.

Russian claims to eastern Anatolia were also accepted, and Italian demands were met with promises of territory in southwest Anatolia.

For Arab leaders who had trusted the commitments made in the Hussein-McMahon Correspondence, these divisions showed the dishonesty of European diplomacy and created deep resentment once the war concluded.

How did the secret agreement become public?

After the Bolsheviks seized power in November 1917, they found documents of secret diplomatic agreements made under the tsarist regime.

On 23 November 1917, the Soviet government published the full text of the Sykes-Picot Agreement in Izvestia and Pravda.

News of the treaty spread quickly when the Manchester Guardian reprinted the documents on 26 November, and Arab leaders learned that European powers had intended all along to partition their lands.

From the Arab perspective, the exposure of the treaty undermined trust in British promises.

Leaders who had committed themselves to the Arab Revolt now understood that their expectations of independence were unrealistic, since France and Britain had already decided how to divide the Middle East.

In 1918, Sharif Hussein asked the British for an explanation, but officials played down the treaty's importance.

For Britain, the revelation created a political problem, and it forced officials to deal with anger from Arab allies while also protecting relations with France.

The profound impacts on the Middle East

In the immediate aftermath of the war, the League of Nations mandate system made the divisions drawn up in 1916 official.

At the San Remo Conference of April 1920, Britain received mandates over Palestine and Mesopotamia, while France assumed control over Syria.

Lebanon was later separated from Syria under French authority. The drawing of these boundaries ignored the tribal loyalties and religious affiliations that bound many communities together, and it cut across long-standing local settlements and created artificial states that would face long-term instability throughout the twentieth century.

In Palestine, tensions increased once the Balfour Declaration of 1917 encouraged Jewish immigration under British supervision.

For Arab inhabitants, the combination of foreign control and the arrival of new settlers increased fears of losing land, which led to violent clashes in the decades that followed.

Elsewhere, revolts in Iraq against British rule in 1920 and the Great Syrian Revolt against French control in 1925 showed that local populations firmly resisted imperial authority.

Over the longer term, the lines drawn in the Sykes-Picot Agreement influenced the structure of modern states such as Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon.

Jordan’s later creation under British mandate in 1921 owed more to subsequent adjustments than to the terms of Sykes-Picot, but it still echoed the imperial thinking established in 1916.

Ultimately, the decisions helped to produce repeated civil wars and serious sectarian conflict, and they created widespread hostility toward Western involvement, all of which stemmed in part from choices that disregarded the hopes of the people who lived in the region.

The secrecy of the agreement, its exposure in 1917, and the contradictions it contained created conditions for a century of conflict in the Middle East.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.