Why did Japan close its doors? Understanding the Sakoku Period

In the early seventeenth century, Japan entered more than two centuries of deliberate isolation from most of the outside world, a policy later known as sakoku (鎖国), or "closed country."

This saw the Tokugawa shogunate impose strict controls on foreign trade and diplomacy, as well as travel into and out of the country.

Only a small number of carefully managed points of contact stayed open, and most Japanese people had no direct contact with outsiders for generations.

Bloody background of Japan's feudal era

During the violent final decades of the Sengoku period, which lasted from the late fifteenth century to the early seventeenth century, Japan’s political authority broke apart as daimyo warlords fought for more territory and political influence.

Power shifted repeatedly as entire provinces changed hands, and large-scale battles such as Nagashino in 1575 and Sekigahara in 1600 killed tens of thousands.

This long period of instability damaged the countryside and left the population weary of constant war.

Under Oda Nobunaga, reunification advanced quickly in the late sixteenth century, as his military campaigns removed the power of many rival lords.

After his assassination in 1582, Toyotomi Hideyoshi continued the process and brought most of Japan under his control by the 1590s.

From the campaigns in Korea in 1592 and 1597, it became clear that Japanese supply networks had limits, and the strain on resources weakened his hold over the country.

Following his death in 1598, Tokugawa Ieyasu took control, and his victory at the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600 enabled him to set up the Tokugawa shogunate in 1603.

In the decades before Tokugawa rule, foreign influence had already taken root in many places of Japan.

In 1543, Portuguese traders arrived at Tanegashima and brought firearms, ship designs, and exotic goods, and Japanese smiths began to produce their own arquebuses almost immediately.

In 1549, Jesuit missionaries led by Francis Xavier, who landed at Kagoshima with Cosme de Torres and Juan Fernández, introduced Christianity, which gained thousands of converts, particularly in Kyushu.

By 1614, when the shogunate issued the first nationwide ban on Christianity, the Christian population was reported at about 300,000, although some modern estimates suggest it may have been slightly lower than this.

The shogunate saw a clear risk of split loyalties, along with interference supported by European colonial powers.

The dramatic declaration of the Sakoku Edict

Under the authority of Tokugawa Iemitsu, the third shogun who ruled from 1623 to 1651, the shogunate introduced broad restrictions on foreign contact.

Between 1633 and 1639, at least five major edicts banned the Japanese from travelling abroad, made it illegal for the return of those who had already left, and limited foreign trade to designated ports under close supervision.

These measures created the basic framework of the sakoku policy.

In Kyushu during 1637 and 1638, the Shimabara Rebellion broke out as thousands of mostly Christian peasants and dispossessed samurai rose against heavy taxation and religious persecution.

Behind the walls of Hara Castle, the rebels resisted for months, and this forced the shogunate to request limited Dutch artillery support under Nicolaes Couckebacker, who was head of the VOC factory at Hirado, in order to break the siege.

Dutch involvement was small but was a demonstration of support for the shogunate.

After the fortress fell, the authorities executed roughly 37,000 people, and this confirmed for the government that Christianity could inspire armed resistance.

In 1639, an edict expelled the Portuguese entirely, cutting off the main source of Christian influence.

Under the new system, only the Dutch, who avoided missionary work, could trade through the artificial island of Dejima in Nagasaki.

Japanese ships were generally limited to a carrying capacity of 500 koku, though enforcement varied.

The real reasons for isolation

In the various official statements, the shogunate stressed the need to keep public order and suppress Christianity.

In reality, the policy addressed a much wider range of strategic concerns. From the Spanish in the Philippines (1565) to the Portuguese in Macao (1557), and the Dutch in Southeast Asia, examples of fast European colonial growth was seen as a warning of what could occur in Japan.

Under the controlled trade system, restricting commerce to Nagasaki allowed the government to monitor transactions, collect taxes, and prevent daimyo from making independent foreign links.

Through Dejima, Japan imported Chinese silk, sugar from the Ryukyu Islands, deerskins from Siam, medicines from the Dutch, and Western books that encouraged the rangaku movement.

By managing imports and exports so tightly, the shogunate kept economic independence and avoided reliance on outside suppliers for vital goods.

For the Tokugawa leadership, internal political security was equally important.

Within the bakuhan system, the relationship between the shogun and the daimyo depended on careful balance.

Foreign alliances or access to advanced weapons could upset that balance, so isolation worked as a safeguard against destabilising influences.

How rigidly was the isolation enforced?

At Nagasaki, officials kept a heavy watch on the Dutch East India Company, and ships were restricted to one or two arrivals per year.

Every transaction passed through approved Japanese agents. The Dutch merchants, who were physically confined to Dejima, lived under guard and required permission for any movement.

In a separate quarter of Nagasaki, Chinese traders operated from the walled Tōjin yashiki compound under equally close watch.

For Korean embassies and Ryukyuan delegations, permitted visits followed strict ceremonial rules, with all interactions recorded by government officials.

Joseon Korea sent 12 official embassies between 1607 and 1811, often decades apart, and the largest arrived in 1711.

Any foreign ship without approval risked being attacked by coastal defences, as in the Morrison Incident of 1837.

For Japanese subjects, restrictions were severe. Travel abroad without permission was punishable by death, and return from overseas exile was forbidden.

Large ocean-going ships were systematically destroyed, and coastal patrols guarded against smuggling or illegal voyages.

Over time, most of the population grew up with little direct knowledge of foreign lands.

What did it take to force Japan to reopen to the world?

In the mid-nineteenth century, foreign pressure increased as Western powers grew their presence in East Asia.

At Edo Bay in 1853, Commodore Matthew Perry arrived with four American steam-powered warships, and gave demands for a treaty that would grant U.S. vessels access to Japanese ports for supplies.

In 1854, Perry returned with nine ships, though not all entered Edo Bay at the same time, and the shogunate, aware of the military superiority of the visitors, agreed to the Treaty of Kanagawa on March 31, 1854.

Under its terms, the ports of Shimoda and Hakodate opened to American ships, a U.S. consulate was created, and shipwrecked sailors would receive care.

Similar treaties with other nations soon followed, which weakened the shogunate’s control over foreign contact and added to political unrest that ended its rule in 1868 with the Meiji Restoration.

Was the Sakoku Era a good or bad thing for Japan?

For more than two centuries, sakoku allowed the Tokugawa shogunate to keep national stability.

As a result, farming output grew and cities expanded, while cultural life developed in distinct ways.

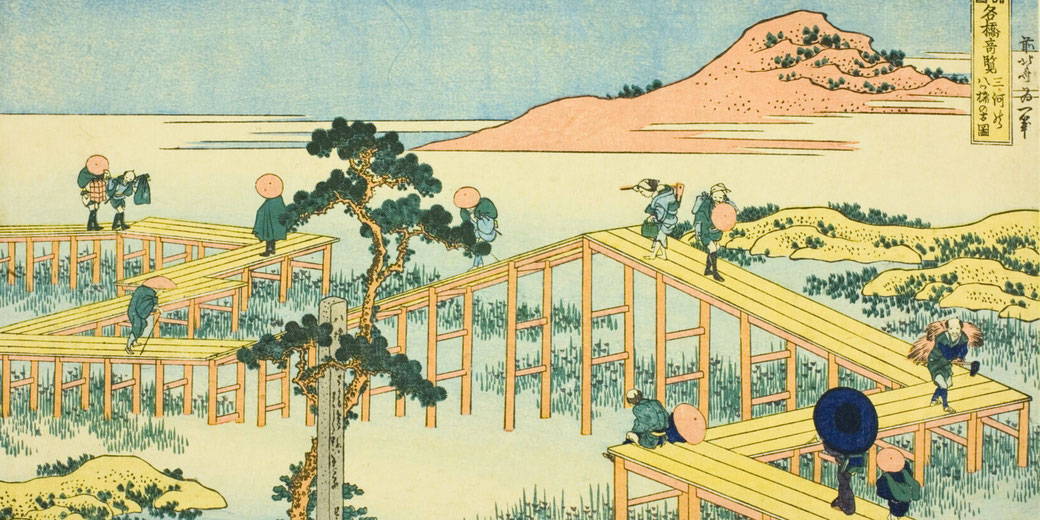

Art forms such as ukiyo-e prints, best demonstrated by Hokusai’s Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, and kabuki theatre flourished, and haiku poetry was refined.

Peace allowed economic growth without the destruction of civil war, and by the early nineteenth century, Japan’s population had reached around 30 million, and it stayed relatively steady afterwards.

From a technological and industrial point of view, isolation slowed Japan’s use of foreign innovations.

Dutch traders brought scientific and medical knowledge through rangaku, which introduced smallpox vaccination and Newtonian physics.

The absence of wider international exchange left the country less ready for the industrialised world of the nineteenth century.

During a period of forceful European growth in Asia, the sakoku system helped keep Japan’s independence.

At the same time, it created a need for quick modernisation once the policy ended, which would be the trigger for major changes in the decades that followed.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.