Rise and Fall of Rasputin: Holy Man or Villain?

Grigori Rasputin gained remarkable access to the Russian royal family during one of the most turbulent periods in the empire’s history.

His influence over the Romanovs shocked the court and outraged the public, and his assassination in 1916 occurred just months before the Russian monarchy collapsed.

The mystery surrounding his life and death has lasted for over a century.

Early life

Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin was born on 21 January 1869 in the remote village of Pokrovskoye in the Tobolsk province of Siberia, where his family lived as peasant farmers.

His father, Yefim, worked as a coachman and landowner, and local records suggest that the household enjoyed modest prosperity.

Rasputin received little education in his early years and remained illiterate well into adulthood, which limited his social opportunities but allowed him to cultivate a reputation based more on charisma than learning.

During his childhood, Rasputin displayed behaviour that many villagers considered unusual or unsettling, and he later claimed to have experienced visions that he interpreted as divine messages.

In his twenties, after he suffered a personal crisis or spiritual awakening, he left his wife and children and embarked on a lengthy pilgrimage to Orthodox monasteries and holy sites across the Russian Empire.

His journey reportedly included plans to visit Mount Athos in Greece, though no solid proof shows he actually got there.

By the early 1900s, Rasputin had developed a personal style of mysticism that blended Orthodox Christian teachings with elements of folk belief and personal revelation.

He began to gather followers in both Siberia and Saint Petersburg, where he presented himself as a single figure who combined prophetic messages, and prayer-based healing.

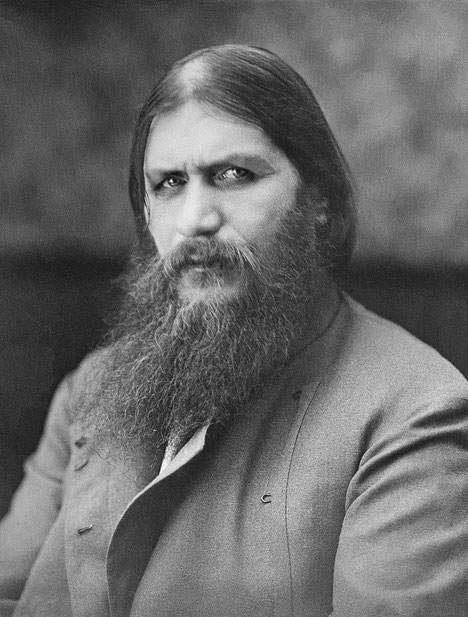

His long hair, unkempt beard, and intense eyes added to his growing legend, while his rejection of established religious institutions made him especially attractive to spiritual seekers who distrusted the official clergy.

Meeting the Romanovs

Rasputin entered the world of the Romanov court in 1905, during a period of national crisis following Russia’s defeat in the Russo-Japanese War and the unrest of the 1905 Revolution.

Tsar Nicholas II and his wife, Alexandra Feodorovna, had become increasingly isolated and distrustful of their ministers, and they turned to spiritual advisors in search of reassurance.

Introduced to the imperial family through the Montenegrin princesses Milica and Anastasia, daughters of King Nicholas I of Montenegro and known for their interest in mysticism, Rasputin quickly impressed Alexandra with his religious conviction and humble origins.

Within a short time, he became a regular visitor to the palace, where he prayed over Alexei and counselled the tsarina during her frequent bouts of anxiety.

Alexandra, who viewed herself as a devout Orthodox Christian and believed in the power of divine providence, considered Rasputin to be a man of exceptional holiness and spiritual strength.

She wrote glowing letters about him to Nicholas and trusted his advice even in matters far beyond medicine.

At court, Rasputin’s rise caused immediate alarm. Nobles, government officials, and church leaders complained about his coarse manners, strange teachings, and disruptive influence on the empress.

Senior members of the Holy Synod, the governing body of the Orthodox Church, launched inquiries into his background, and police surveillance produced reports of his drunken behaviour and sexual misconduct.

In 1911, Bishop Hermogen and Archimandrite Iliodor publicly denounced Rasputin and were later exiled for defying the court's protection of him.

Despite these warnings, Nicholas refused to ban Rasputin from court, largely because Alexandra continued to insist that he had saved their son and been chosen by God.

As Rasputin’s authority expanded, his enemies began to describe him as a dangerous fraud who manipulated the royal family and undermined national stability.

Political cartoons portrayed him as a hypnotist or magician, while popular pamphlets accused him of seducing court ladies and spreading corruption throughout the empire.

The secrecy surrounding his visits to the palace only strengthened the public’s belief that he controlled the throne from behind the scenes.

His 'magical powers'

Rasputin’s reputation as a man of special ability spread rapidly once people began to credit him with amazing healing acts, particularly in cases where conventional medicine had failed.

His most famous case involved the young heir to the Russian throne, Alexei Nikolaevich, who suffered from haemophilia, a hereditary blood disorder passed down from Queen Victoria through Alexandra’s family line, and regularly endured life-threatening internal bleeding.

When court doctors could offer no solution, Rasputin provided calming prayers and advice that, according to those present, seemed to ease the boy’s suffering.

Eyewitnesses described Rasputin using a combination of soft words with ritual gestures during long meditation sessions to treat Alexei, and many believed that he possessed the power to stop bleeding or reduce pain through spiritual energy alone.

In one critical incident on 5 October 1912, while Alexei lay near death in the imperial hunting lodge at Spala, Rasputin sent a telegram instructing the tsarina to stop all medical treatments and trust in God’s will.

Shortly afterward, the boy began to recover, and Alexandra concluded that Rasputin’s prayers had saved her son’s life.

However, modern interpretations suggest the improvement may have coincided with the cessation of aspirin, which worsened bleeding.

Modern scholars have proposed several explanations for Rasputin’s apparent success as a healer.

At the same time, rumours about Rasputin’s immoral private life began to circulate through the salons and streets of Saint Petersburg.

Witnesses reported that he drank heavily, consorted with prostitutes, and made sexual advances toward women who came to him for spiritual advice.

These contradictions between his public role as a man of God and his private behaviour as a libertine generated deep suspicion and widened the divide between his supporters and critics.

His power over the imperial family

Rasputin’s real political power became evident during the First World War, when Nicholas II departed for military headquarters at Mogilev in 1915 and left Alexandra in control of domestic affairs.

The empress grew increasingly reliant on Rasputin’s guidance and began to consult him on ministerial appointments and state matters, even though he held no official position and lacked administrative training.

Between 1915 and 1916, Rasputin influenced a series of cabinet changes that removed experienced ministers and replaced them with men who lacked competence but had earned his favour.

These included controversial appointments such as Boris Stürmer as Prime Minister and Alexander Protopopov as Minister of the Interior, both widely criticised for their inefficiency.

These decisions disrupted the already fragile state bureaucracy and created further resentment among the aristocracy, the Duma, and the military command.

Critics accused Rasputin of exploiting the war to expand his influence and using his proximity to the tsarina to act as a puppet master within the palace.

While ordinary Russians endured inflation, food shortages, and conscription, newspapers and gossip networks focused obsessively on Rasputin’s latest excesses.

He reportedly accepted bribes, interfered in military decisions, and maintained a circle of female admirers who treated him as a holy prophet.

Imperial police kept detailed records of his public drunkenness and visits to brothels.

Some accounts, though exaggerated, described scenes of drunken orgies and blasphemous rituals in his private apartment.

These stories reinforced the image of a man who used religion as a cover for personal indulgence and political manipulation.

The widespread belief that Rasputin had bewitched the empress and exercised unnatural control over the government turned him into a national obsession.

Rumours swirled that he had promised victory at the front and guaranteed the safety of the imperial family through spiritual means.

His enemies believed that as long as Rasputin remained alive and close to the palace, Russia would continue to descend into chaos and revolution.

Downfall and murder

By the end of 1916, a group of conservative nobles decided that killing Rasputin was the only way to fix Russia’s political crisis.

The plot included Prince Felix Yusupov, Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, and Vladimir Purishkevich, who feared that Rasputin’s influence had destroyed public confidence in the monarchy.

They resolved to murder him in secret to avoid scandal and preserve the dignity of the throne.

On the night of 16 December, the conspirators lured Rasputin to the Moika Palace under the pretext of meeting Yusupov’s wife.

Once inside, they served him cakes and wine that they claimed had been laced with cyanide.

They expected him to collapse quickly. However, the official autopsy did not find any trace of poison in his body, leading many historians to doubt that cyanide was ever used.

When the poison failed to act, Yusupov retrieved a revolver and shot him in the chest.

Believing him dead, the plotters briefly left the room, only to return and find Rasputin attempting to flee across the courtyard.

In a state of panic, they shot him again, beat him with a metal bar, and finally bound his hands and feet before dumping his body into the icy Neva River.

Later examination reportedly revealed water in his lungs, which some took as evidence that he had still been alive when submerged.

However, this finding remains contested by modern scholars due to the destruction of the original autopsy report.

His corpse was discovered days later, and Alexandra reacted with shock and rage, demanding a full inquiry.

Nicholas issued mild punishments to those involved, but no one faced serious consequences.

Purishkevich publicly defended the murder in a Duma speech the next day and was applauded by many, while Yusupov did not admit his involvement at the time and only described it in later memoirs..

The murder failed to remove the underlying problems that Rasputin had come to symbolise.

Rather than restoring the monarchy’s credibility, the assassination revealed its weakness and exposed the divisions among the elite.

Rasputin’s death, carried out by members of the nobility, showed how far trust in the tsar’s leadership had collapsed, even within his own class.

Saint or a master manipulator?

Interpretations of Rasputin’s life vary sharply between those who view him as a man of sincere religious devotion and those who consider him a cynical opportunist.

His supporters, many of whom came from the peasantry and fringe religious groups, praised the depth of his spiritual insight alongside the humility he displayed and the healing gifts he shared.

They believed that he had sacrificed comfort and reputation to serve the royal family and fulfil a divine mission.

Opponents, however, described him as a manipulative figure who cloaked personal ambition in the language of holiness.

They argued that he used prayer and ritual as tools to dominate others, especially women who looked to him for guidance during emotional or physical suffering.

His refusal to follow Orthodox discipline and his frequent indulgence in worldly pleasures undermined his claims to sanctity.

Historians continue to debate whether Rasputin genuinely believed in his spiritual powers or invented them to gain influence.

Some point to his simple background, lack of education, and occasional expressions of humility as signs of sincerity.

Others cite the calculated nature of his political manoeuvres and his survival amid multiple scandals as evidence of a man who knew exactly how to manipulate people and exploit crises for personal benefit.

Over time, his myth expanded in popular culture, from sensational memoirs to the 1978 song by Boney M, which immortalised the legend of the "mad monk" whose influence helped bring down an empire.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.