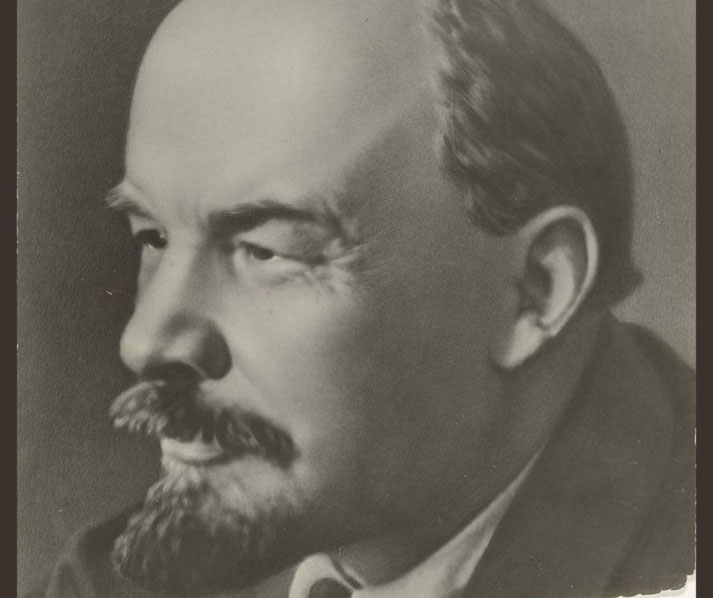

From exile to power: The revolutionary journey of Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin led a revolution that overthrew centuries of rule by autocrats and created what the Soviet leadership called "the world’s first socialist state".

As the leader of the Bolshevik movement, he combined Marxist theory with practical political action, and his influence continued for decades after his death.

Lenin's journey from provincial student to exiled theorist, and eventually to head of state, is a gripping story of a largely relentless pursuit of radical change that was motivated by firm political beliefs and cunning political strategy.

Lenin's early life

Vladimir Ulyanov was born on 22 April 1870 in the Volga River town of Simbirsk, which would later be renamed Ulyanovsk.

His father was Ilya Ulyanov, who worked as a state school inspector and had received hereditary nobility status for his service to the tsarist government, while his mother, Maria Alexandrovna Blank, came from a a mixed family background that combined German and Jewish elements with Russian roots.

The household placed a high value on education, and all six children were encouraged to study carefully.

It is said that Vladimir displayed early talent in classical languages such as Latin and Greek.

A key moment came in 1887, when his elder brother Aleksandr Ulyanov, a member of the revolutionary group People's Will, was arrested and executed for participating in a plot to assassinate Tsar Alexander III.

Their father had died only the previous year, which deepened the emotional impact of the execution on the seventeen-year-old Lenin, who began to question the legitimacy of the Russian monarchy and rejected religious belief.

Although he enrolled at Kazan University to study law, his involvement in a student protest led to expulsion, and though later permitted to complete his studies externally at St. Petersburg University, he would remain under police surveillance for years to come.

By the early 1890s, Lenin had passed his law examinations, had briefly worked as a legal assistant, and had begun to read political literature, especially the works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels.

He studied economic theory, wrote political essays, and began networking with secret socialist groups, and he gradually moved from academic interest to revolutionary plans.

Becoming a political radical

After he moved to St. Petersburg in 1893, Lenin established connections with Marxist intellectuals and joined illegal discussion groups that were primarily composed of intellectuals, in which participants debated economic exploitation and autocracy.

He contributed articles to underground journals and advocated for a political movement grounded in Marxist doctrine.

When he co-founded the Union of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class in 1895, he aimed to unify separate socialist groups into a united revolutionary force that could confront the state.

However, his political activity drew the attention of the Okhrana, and he was arrested in late 1895 for his involvement in revolutionary organising.

After he had spent more than a year in prison, he was sentenced to internal exile in the remote Siberian village of Shushenskoye, where he remained from 1897 to 1900.

During this period, he married Nadezhda Krupskaya, a committed Marxist he had met through the revolutionary movement, and he continued to write articles and theoretical essays that would lay the foundation for future political debates within the Russian socialist movement.

In 1899, he published The Development of Capitalism in Russia, which was an important economic work that criticised the persistence of feudal structures and argued that capitalist relations had taken root in rural areas.

After completing his term of exile, Lenin left Russia and began organising revolutionary activity from abroad.

In 1900, he helped launch Iskra ("The Spark"), a Marxist newspaper published in Western Europe and smuggled into Russia to spread revolutionary ideas.

Through Iskra, he advocated for greater discipline within the movement and a central leadership, that would become a key issue in the party's future development.

Lenin's revolutionary activities before 1917

During the Second Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) in 1903, held first in Brussels and later in London, a bitter split over ideas occurred, with Lenin forming the Bolshevik faction that demanded a tightly organised party of professional revolutionaries.

He rejected the Menshevik position, which favoured a broader and more inclusive party led by Julius Martov.

This division set the stage for future conflict and shaped the organisational structure of the revolutionary movement.

The failure of the 1905 Revolution, which began after Bloody Sunday and culminated in mass strikes and peasant uprisings, confirmed Lenin's belief in the necessity of armed insurrection and centralised revolutionary leadership.

Though the revolution resulted in some concessions, such as the creation of the Duma, Lenin remained unconvinced that reform could produce real change.

During that year, the St. Petersburg Soviet, which was a new model of worker-led political organisation, was briefly chaired by Leon Trotsky.

Lenin continued to lead the Bolsheviks from exile in Geneva, Paris, and other cities, writing political treatises and engaging in debates with other Marxist thinkers.

During the First World War, Lenin argued that the war was a clash between imperialist powers, and he firmly criticised European socialist parties that had supported their national war efforts.

In his 1916 work Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, published the following year, he analysed the global economy and explained how colonial expansion and monopolies led to war.

His stance set him apart from many fellow socialists, but it reinforced his commitment to support for revolution in other countries and the need for class struggle.

The February Revolution and Lenin's return

When the February Revolution broke out in Petrograd in 1917, strikes and mass protests over food shortages and military failures rapidly escalated.

The tsar abdicated, and a Provisional Government, led by liberal and moderate socialist leaders, assumed control.

At the same time, the Petrograd Soviet, composed of workers and soldiers’ representatives, also claimed authority, which created a situation of dual power in the country.

From exile in Zurich, Lenin learned of the uprising and immediately began planning his return.

With assistance from the German government, which hoped to destabilise Russia’s Eastern Front and weaken its war effort, Lenin travelled in a sealed train across Germany and Sweden.

He arrived at Petrograd’s Finland Station on 3 April 1917 and was greeted by a sizeable crowd of supporters and party comrades.

Shortly after his arrival, Lenin delivered the April Theses, in which he demanded an end to the war, the state control of all land, and power to the soviets, along with the abolition of the police, army, and bureaucracy.

He also condemned the Provisional Government as a continuation of bourgeois rule and insisted on the need for a second revolution to establish a socialist state.

These radical demands split the socialist movement but won growing support among workers, soldiers, and peasants who had lost faith in the new government’s ability to resolve Russia’s crisis.

The October Revolution

By the middle of 1917, the Bolsheviks had gained increasing influence in the soviets, and support for Lenin’s call for a second revolution had grown.

In July, after a failed uprising against the Provisional Government, Lenin fled to Finland to avoid arrest, but he continued to direct party activity through letters and secret meetings.

He pushed for immediate action, convinced that waiting would allow rival factions to secure power.

On 24, 25 October 1917 (6, 7 November, New Style), the Bolsheviks launched a carefully planned armed insurrection in Petrograd.

Red Guards and soldiers loyal to the Bolsheviks took control of bridges, government buildings, and the telegraph office.

By the morning, they had stormed the Winter Palace, which was lightly defended by military cadets and members of the Women’s Battalion.

They gradually arrested the ministers of the Provisional Government over several hours. The Provisional Government had been led by Alexander Kerensky.

The Congress of Soviets met shortly after and ratified the transfer of power, creating the Council of People’s Commissars (Sovnarkom) with Lenin as its chairman.

The new government issued immediate decrees on peace and land, and on workers’ control of production, which began a transformation of Russian society that altered the global political order.

Lenin in power

As leader of the Soviet government, Lenin oversaw a period of major change and great turmoil.

In March 1918, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk ended Russia’s involvement in the First World War but resulted in the loss of large territories, including Ukraine, Finland, the Baltic states, and parts of Poland.

The treaty had been signed on 3 March 1918 and specifically cost Russia approximately one-third of its population, about half of its industry, and nine-tenths of its coal mines.

Though widely unpopular, Lenin believed that peace was necessary to consolidate power and preserve the revolution.

At the same time, the country descended into civil war. The Red Army, which was organised by Leon Trotsky, fought against the White Armies, which included monarchists, nationalists, and foreign interventionists from Britain, France, the United States, and Japan.

To control the economy and supply the army, Lenin implemented War Communism, which included taking grain from peasants, forced labour, and the state control of industry.

The policy led to famine, rebellion and economic collapse, but the Bolsheviks eventually won the war by 1921.

However, the Civil War also gave rise to the Red Terror, a campaign of political repression led by the Cheka, the Bolshevik secret police.

Thousands of real or suspected opponents were imprisoned or executed, and political pluralism vanished.

In July 1918, the Romanov family was executed by Bolshevik forces. Although the Red Terror officially began weeks later, the execution has often been retrospectively associated with the wider campaign of political violence.

After the Civil War had ended, Lenin introduced the New Economic Policy (NEP) in March 1921, which allowed limited private trade and market activity, particularly in agriculture.

The NEP replaced grain requisitioning with a fixed tax in kind that allowed peasants to sell any surplus and was intended to restore food production and prevent further unrest, even though it displeased many in the Communist Party.

Declining health and death

In May 1922, Lenin suffered a series of strokes that severely impaired his speech and mobility.

Although he returned briefly to political activity, including dictating letters and memos that warned against the growing influence of Joseph Stalin, his condition worsened.

In his Testament, which was written between December 1922 and January 1923, he criticised Stalin’s conduct and recommended his removal from the post of General Secretary, though party leaders later suppressed the document.

By March 1923, he had become completely unable to take part in state affairs or party leadership.

He spent his final months at Gorki, a country estate outside Moscow, where he was under the care of his wife and doctors.

Then, on 21 January 1924, Vladimir Lenin died at the age of 53, which prompted widespread grief across the Soviet Union.

The government preserved his body and placed it in a specially built mausoleum on Red Square.

Soon after, the city of Petrograd was officially renamed Leningrad on 26 January 1924 in his honour.

In the years that followed, Lenin’s writings and image were used to justify policies and actions that often diverged from his original vision, and his name became a political emblem.

However, the revolution he led overturned the old order and created a new political model that would influence the 20th century, both in Russia and across the world.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.