The history behind the Israel-Iran Conflict

The relationship between Israel and Iran has changed dramatically from the mid-20th century to today. In the decades after World War II, the two countries were surprisingly friendly.

But since the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran, they have become bitter adversaries. Much of today’s problems are the result of a series of events over the last 50 years.

Allies on the “Periphery” from 1940s to 1970s

When the State of Israel was established in 1948, Iran’s first response was unclear.

Iran had opposed the United Nations plan for the division of Palestine and voted against Israel’s admission to the UN.

Yet in 1950, Iran became the second Muslim-majority country after Turkey to recognise the new nation of Israel.

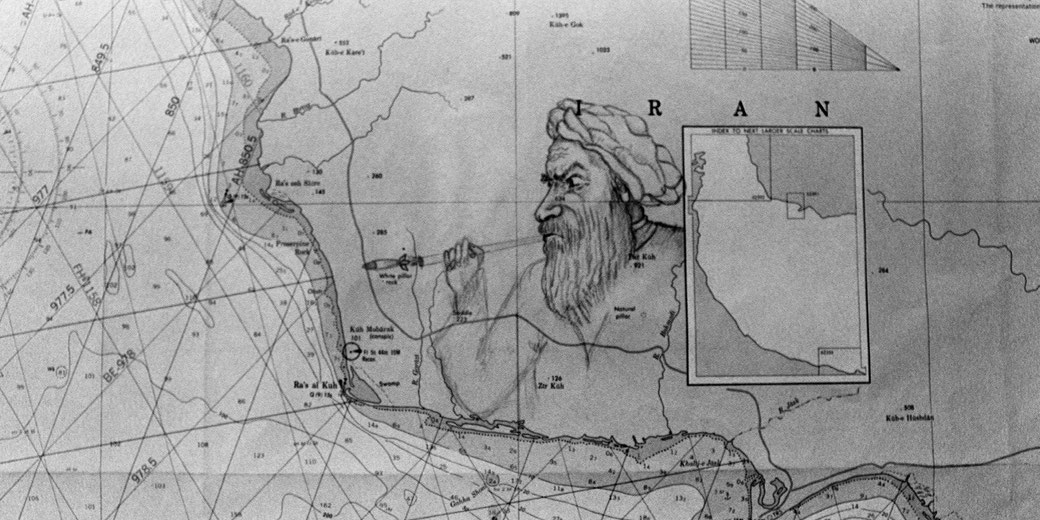

Under Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s monarchy that supported the West, Iran and Israel developed close ties.

Both were non-Arab states surrounded by mostly Arab neighbours, so they saw each other as natural partners against shared regional threats.

This idea was part of Israel’s “alliance of the periphery” strategy in which they sought partnerships with non-Arab countries on the Middle Eastern periphery.

During the 1960s and 1970s, Iran and Israel had shared strong official and trade cooperation and engaged in military collaboration.

Iran supplied oil to Israel and even jointly operated an oil pipeline with Israel.

Trade was strong, with Israeli companies and experts active in Iran. The two countries exchanged informal diplomatic offices, a de facto embassy in Tehran, and later official ambassadors in the 1970s.

There were also hidden military projects; for example, Iran and Israel worked together on a missile project in the late 1970s.

At the same time, however, not all Iranians were supportive of this closeness.

Some Iranian religious leaders criticised the Shah for his friendship with Israel and sympathised with the Palestinian cause.

Overall, until the late 1970s, the political and diplomatic relationship between Israel and Iran was mostly positive and cooperative.

The 1979 Islamic Revolution: From Friends to Foes

This friendly relationship ended suddenly in 1979 with Iran’s Islamic Revolution when the Shah was overthrown and Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini established an Islamic Republic.

The new regime was fiercely anti-Israel on grounds of belief and religion. Iran cut off all official ties with Israel; they closed the Israeli mission in Tehran and handed the building over to the Palestine Liberation Organisation, PLO.

Khomeini and the revolutionary government viewed Israel as a unlawful, unfair government over Muslims; he famously declared Israel to be the “enemy of Islam” and labeled it the “Little Satan” (in contrast to the United States, the “Great Satan”).

In the eyes of Iran’s new leaders, Israel represented Western imperialism and unfair treatment of the Palestinian people.

From 1979 onward, Iran’s policy became one of open hostility toward Israel, based on both politics and religion.

Some historians note that Iran’s new rulers, who denounced Israel, did not entirely lose sight of geopolitical realities.

In the chaotic days of the revolution and afterward, Iran and Israel found themselves with a common enemy in Saddam Hussein’s Iraq.

This would soon lead to secret interactions even amid official enmity.

The Iran-Iraq War and Secret Dealings (1980 to 1988)

In September 1980, Iraq, under Saddam Hussein, invaded Iran, which sparked the Iran–Iraq War.

Interestingly, Israel, officially an enemy of post-revolution Iran, chose to quietly assist Iran during this war.

Israel’s government reasoned that Iraq was the bigger danger at the time, since Iraq had a powerful military and had also been hostile to Israel.

When Israel helped Iran defend against Iraq, it hoped to keep both of its potential adversaries weakened.

It also saw an opportunity to regain some influence in Iran that was lost after the Shah’s fall.

Throughout the war from 1980 to 1988, Israel became one of Iran’s most important secret arms suppliers.

Israeli shipments included spare parts, ammunition and weapons that Iran desperately needed, all arranged through secret channels.

Israeli military instructors reportedly even helped train Iranian forces during the conflict.

In return, Iran provided Israel with intelligence on Iraq; in particular, information from Iran helped Israel carry out the 1981 airstrike that destroyed Iraq’s Osirak nuclear reactor.

That reactor was believed to be part of Iraq’s effort to build nuclear weapons, so both Iran and Israel had an interest in eliminating it.

Publicly, Iran’s leaders maintained their anti-Israel stance and denied any cooperation with “the Zionist regime”.

For Iran’s revolutionary government, admitting to working with Israel would have been politically damaging and against their ideological line.

Likewise, Israel did not advertise its support for the Khomeini regime. Even as they traded arms covertly, Iran and Israel remained officially hostile throughout the 1980s and that hostility would soon appear in new ways after the Iran–Iraq War.

Iran’s Support for Anti-Israel Movements (1980s to 1990s)

After 1979, while Iran opposed Israel rhetorically, it also began supporting militant groups that fought Israel.

A major development was the rise of Hezbollah in the 1980s. In 1982, Israel invaded southern Lebanon during the Lebanese Civil War and aimed to destroy the PLO bases there.

In response, Iran sent Revolutionary Guard troops into Lebanon to organise and assist local Shi’ite militias.

With Iran’s support, these militias formed Hezbollah (Arabic for “Party of God”), an Islamist guerrilla organization.

Iran provided Hezbollah with guidance in their beliefs, funding, weapons, and training, which turned it into a potent force against Israel.

Hezbollah’s goal was to resist the Israeli occupation of southern Lebanon, and it carried out attacks against Israeli troops and Northern Israel.

This was a clear example of Iran’s new proxy strategy: instead of direct battle, Iran used allied militias to harass and fight Israel.

Over time, Hezbollah grew into one of Iran’s strongest proxies and a major adversary of Israel.

The Hezbollah-Israel conflict continued for decades, including a full-scale war in 2006 in which Hezbollah fired rockets into Israel and Israel bombarded Lebanon.

Iran also provided support to Palestinian militant groups. At first, Iran tried to form ties with Yasser Arafat’s PLO after 1979, and it presented itself as a supporter of the Palestinian cause.

However, the PLO was Sunni-led and had doubts about Shi’ite Iran’s motives. Over time, Iran found partners with similar beliefs in groups that rejected any peace with Israel, notably Palestinian Islamic Jihad, or PIJ, and later Hamas.

These groups, which were based in the Palestinian territories, share Iran’s refusal to accept Israel’s right to exist and have carried out armed attacks against them.

Iran became a financial and military backer for both PIJ and Hamas, especially from the late 1980s onward.

For example, Hamas, a Palestinian Islamist movement that emerged during the First Intifada in 1987, received weapons and funds from Iran.

Iran’s supreme leaders routinely called for the liberation of Palestine and showed support for these groups as a religious duty.

When it supported the Palestinian resistance, Iran also sought to gain reputation in the wider Muslim world, including among Sunni Arabs, by showing it was taking action against Israel, something many Arab governments were reluctant to do.

This period also saw terrorist attacks linked to Iran’s proxies. In 1992, the Israeli Embassy in Buenos Aires was bombed, and in 1994, a Jewish community center (AMIA) there was bombed, killing scores of civilians.

Investigations implicated Hezbollah operatives with Iranian backing in these attacks.

Such incidents showed how Iran’s conflict with Israel became global rather than confined to the Middle East.

By the early 1990s, through groups like Hezbollah, Hamas, and PIJ, Iran was involved in a covert war with Israel.

From Israel’s perspective, Iran was now the center of an anti-Israel “axis,” and it armed and funded attacks on Israeli civilians and interests.

This proxy warfare added a major military and religious aspect to the Israel-Iran conflict: it shifted from state-to-state hostility to a broader struggle involving non-state Islamist fighters who were motivated by religion and revolutionary ideology.

From Cold Peace to Open Hostility in the 1990s

Up until the late 1980s, one could describe the Israel-Iran relationship as a cold peace (especially given their tacit cooperation during the Iran-Iraq War).

But the 1990s brought in a new period of open hostility. Several factors contributed to this increase.

First, the end of the Cold War and changes in the region shifted strategic aims. The Soviet Union fell apart in 1991, and Iraq was weakened after defeat in the 1991 Gulf War; as a result, Israel no longer saw its neighboring Arab states as its most immediate threats.

Instead, Israeli leaders started to view Iran as the next threat. In the early 1990s, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin’s government adopted a tough approach toward Iran.

Iran’s continued support for anti-Israel militants and its rhetoric were now on Israel’s radar.

On the Iranian side, strict positions against Israel only grew stronger. In 1989, Ayatollah Khomeini died, but the regime’s hostility to Israel continued under new Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei.

In the mid-1990s and into the 2000s, Iran’s government and media often denied Israel’s right to exist and even denied the Holocaust or made other inflammatory statements.

Perhaps most notably, Iran elected President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in 2005, who became notorious for strong anti-Israel statements.

He was reported as saying that “the occupying regime must be wiped off the map,” causing international anger; the exact translation is debated, but the message of hostility was clear.

Such political rhetoric convinced Israelis that the Iranian regime was firmly determined to destroy Israel if it could.

Another major factor was the new issue of Iran’s nuclear program (which we explore more in the next section).

In the 1990s, Western intelligence began thinking that Iran tried to develop nuclear weapons.

The chance of a nuclear-armed Iran very worried Israel and added a new dimension to the conflict.

Meanwhile, Iran’s continued funding of groups like Hezbollah and Hamas led to further violence.

For instance, Hezbollah’s cross-border attacks continued through the 1990s, and Hamas carried out suicide bombings during the Second Intifada (early 2000s).

Israel responded with military force, sometimes directly against Iranian interests.

Israeli agents were believed to be active in efforts to stop Iran-backed networks, and Israeli warplanes periodically struck Hezbollah targets.

In 1996, Israel launched “Operation Grapes of Wrath” against Hezbollah in Lebanon, an example of how the conflict played out via proxies.

By the end of the 1990s, the diplomatic situation was one of open hostility: Iran had no relations with Israel and often referred to it as the “Zionist regime” to avoid even uttering “Israel”.

Israel, for its part, began preparing its public for the possibility of future confrontation with Iran.

Israeli officials and analysts frequently cited Iran as a serious threat , a nation that might one day attempt to annihilate Israel.

Nuclear Tensions and “Shadow War” (2000s to 2010s)

In August 2002, an Iranian opposition group revealed the existence of a secret uranium enrichment facility at Natanz, which Iran had not declared to international inspectors.

This discovery showed that fears were true: Iran was pursuing nuclear technology that could potentially be used for atomic bombs.

From that point on, Israel’s government made it their main concern that Iran could not obtain nuclear weapons (as well as for many Western countries).

Israel views a nuclear-armed Iran as an unacceptable threat to its national survival.

Iranian leaders’ threatening remarks, such as predicting Israel’s eventual “demise,” only heighten these fears.

Israeli officials often state that Iran’s nuclear program is designed to give Tehran the capability to destroy Israel, and so Israel must stop it at any cost.

In fact, Israel has explicitly said that it reserves the right to act militarily to prevent an Iranian bomb.

As one recent analysis briefly stated, Israel sees the nuclear program that advanced as a direct threat to Israel’s existence.

On the diplomatic front, there have been efforts to rein in Iran’s nuclear ambitions.

After years of talks, Iran and six world powers, which included the US, reached the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in July 2015.

This agreement put strict limits on Iran’s nuclear activities, including measures that capped uranium enrichment and that allowed inspections in exchange for lifting economic sanctions.

The deal was meant to delay any Iranian path to a bomb, at least for a decade or more.

However, Israel was one of the deal’s harshest critics. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu argued that the JCPOA was flawed because Iran could resume enrichment when the deal’s terms expired, and that it didn’t address Iran’s missile program or support for militants.

In 2018, the United States under President Donald Trump unilaterally withdrew from the nuclear deal, a move cheered by the Israeli government.

After the US exit, Iran also began breaching the deal’s limits. By 2021, Iran had increased uranium enrichment to 60% purity, its highest level ever, and much closer to weapons-grade (90%).

Each such step intensified Israeli alarm by shortening the so-called “breakout time” for Iran to potentially make a bomb.

Apart from diplomatic measures, an ongoing secret war has been waged to slow Iran’s nuclear progress.

In 2010, the Stuxnet computer virus, which was widely believed to be a joint U.S.-Israeli creation, infiltrated Iran’s Natanz facility and sabotaged many of its centrifuges.

Throughout the 2010s, a number of Iranian nuclear scientists were mysteriously assassinated, for example, by magnetic bombs attached to their cars.

Iran blamed Israel for these killings, and most observers believe Israeli intelligence agencies were indeed behind them.

In November 2020, Iran’s top nuclear scientist, Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, was killed in an ambush that Iran also attributed to Israel.

Meanwhile, Iran or its proxy forces have attempted reprisals that ranged from cyberattacks on Israeli infrastructure to plotted attacks on Israeli citizens abroad.

These reciprocal actions have largely occurred in the shadows, but occasionally it flares into more visible incidents.

Military tension has also increased in other theatres as part of this Iran-Israel struggle.

In Syria, during the Syrian Civil War (2011 to 2025), Iran deployed forces and militias to support the Assad regime.

Israel, concerned that Iran was building bases or transferring advanced weapons to Hezbollah, conducted hundreds of airstrikes in Syria over the past decade, which targeted Iranian shipments and personnel.

These Israeli strikes aimed to prevent Iran from establishing a strong military foothold next door.

At times, Iranian operatives or proxy fighters in Syria have launched missiles or drones toward Israel.

Similarly, in Yemen’s war, Iran-backed Houthi rebels have voiced hostility toward Israel, and there have been instances of Houthi missiles or drones headed toward Israel (as happened in 2023) which Israel intercepted.

The Abraham Accords (2020) and Regional Diplomacy

While Israel and Iran have been locked in rivalry, the diplomatic map of the Middle East has shifted in ways that affect their conflict.

A significant recent development was the signing of the Abraham Accords in 2020.

These agreements, which were brokered by the United States, normalised relations between Israel and several Arab states, notably the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Bahrain, later joined by Morocco and Sudan.

This was a historic breakthrough because, previously, most Arab states refused to recognise or deal openly with Israel.

The accords led to official peace and cooperation between Israel and those countries, opening official trade and travel arrangements and establishing diplomatic ties.

A major driver behind the Abraham Accords was a shared fear of Iran’s growing influence.

The UAE, Bahrain and Saudi Arabia, which quietly supported the process, view Iran as a strategic threat to the Gulf region.

Iran’s activities, from its nuclear program to its backing of militias in Arab countries, have deeply alarmed these Sunni Arab monarchies.

As a result, former rivals found common cause: when they teamed up with Israel, Arab states hoped to strengthen a regional group against Iran.

In return, Israel gained new allies and recognition in the region, as well as economic opportunities.

One analysis noted that the promise of advanced technology and trade, “which was motivated by a shared view of Iran as a strategic threat,” helped drive these agreements.

From Iran’s perspective, the Abraham Accords were a worrying development.

Tehran saw them as an attempt by the US and Israel to surround Iran with hostile alliances.

Iranian officials strongly criticised the UAE and Bahrain for “betraying” the Palestinian cause and siding with Israel.

Iran’s Supreme Leader said these Arab states would become involved in Israel’s plans and warned of consequences.

Strategically, Iran has tried to counter this to strengthen its own regional ties. For instance, Iran improved relations with Qatar and Oman.

It even reached out in 2023 to mend fences with Saudi Arabia through a China-brokered deal.

These steps partly broke the united front forming against it. Nevertheless, the Abraham Accords remain in place and have mostly survived subsequent regional crises.

They represent a diplomatic shift that isolates Iran further: Israel is no longer as isolated among its neighbours, and Iran faces an unspoken alliance of Israel and Sunni Arab states united by anti-Iran sentiment.

It’s worth noting that the Abraham Accords initially sidestepped the Palestinian issue and focused on mutual benefits and the Iran threat.

However, when war broke out between Israel and Hamas in 2023, as described below, it did strain Israel’s new Arab friendships.

Those countries faced public anger and had to balance their strategic partnership with Israel against solidarity with Palestinians.

Recent Developments: Towards 2025

In the early 2020s, the Israel-Iran conflict remains extremely unstable, with events that highlight how shaky the situation is.

One of the most important recent events was the Israel-Hamas War of 2023. On October 7, 2023, the Gaza-based armed group Hamas launched a surprise attack on Israel.

This attack killed around 1,200 people. Hamas is armed and financed in part by Iran, and Iranian leaders praised the attack.

Iran’s Supreme Leader praised the “resistance,” and Iran’s government openly celebrated Israel’s moment of pain.

Although Iranian state media denied direct involvement, they did call it a fair fight against Zionism.

During the following Gaza war, Iran provided political support to Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad.

It also reportedly supplied weapons and worked with its allies to put pressure on Israel.

For example, Hezbollah in Lebanon, another Iranian ally, fought Israeli forces on the northern border during the Gaza conflict, although a full second front did not open.

Pro-Iranian militias in Iraq and Syria also threatened to join. This raised fears that the 2023 Gaza war could turn into a wider regional war involving Iran directly.

No direct Iran-Israel war started in 2023. Several near misses and events followed it.

In late 2023 and early 2024, Iran’s Revolutionary Guard forces were put on alert, and Israel warned that if Iran tried to attack directly, Israel would fight back strongly.

Fights continued through indirect forces. For instance, in early 2024, there were reports of Israeli airstrikes on targets linked to Iran in Syria and even Iraq, in response to attacks on US bases by Iran-backed groups.

In one incident reported in April 2024, an Israeli strike hit an Iranian facility in Syria, and Iran in turn launched a sudden volley of missiles and drones toward Israel, most of which were intercepted.

Israel also allegedly carried out operations even on Iranian soil, including sabotage of infrastructure.

In 2024, the long-running secret war became more open, with clear military action blamed on each side.

Some experts have said that this period was a gradual move toward direct conflict.

Another change has been new leaders and how they affect the conflict. In Israel, Benjamin Netanyahu, a tough leader on Iran, returned to power in late 2022, and he kept Israel’s policy strict.

Netanyahu has often said Israel will act alone if needed to stop an Iranian bomb. In Iran, the election of President Ebrahim Raisi, a tough cleric, in 2021, showed no easing toward Israel.

Under Raisi and Supreme Leader Khamenei, Iran has grown even closer to militant groups and to Russia, for example, Iran supplied drones to Russia in 2022.

This suggests Iran feels encouraged to oppose Israel and Western countries, in spite of its economic troubles at home.

In talks to bring back the 2015 nuclear deal, efforts failed by 2022, and as a result, there is no agreed limit on Iran’s nuclear work right now.

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has warned that Iran has stockpiled highly enriched uranium.

This led to serious talks in Israel and internationally about possible military action. By early 2025, Israel’s military was openly conducting drills that simulated strikes on Iran’s nuclear facilities, and Israeli officials urged the US and others to adopt tougher measures.

Iran, for its part, issued threats that any attack would be met with massive missile barrages on Israeli cities and that it could ignite conflicts on multiple fronts: Lebanon, Gaza, Syria, etc.

The language on both sides has been extremely heated.

As of May 2025, the Israel-Iran conflict shows no sign of a solution. It is closer to the surface than ever.

Both nations have been in a long-term cold war that occasionally turns hot through proxy battles.

The factors at play include deep ideological hostility. Iran’s religious leadership refuses to recognise Israel and calls for its elimination.

Israel sees Iran’s regime as bent on its destruction.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.