The complex and conflicted history of the Palestinian people before 1948

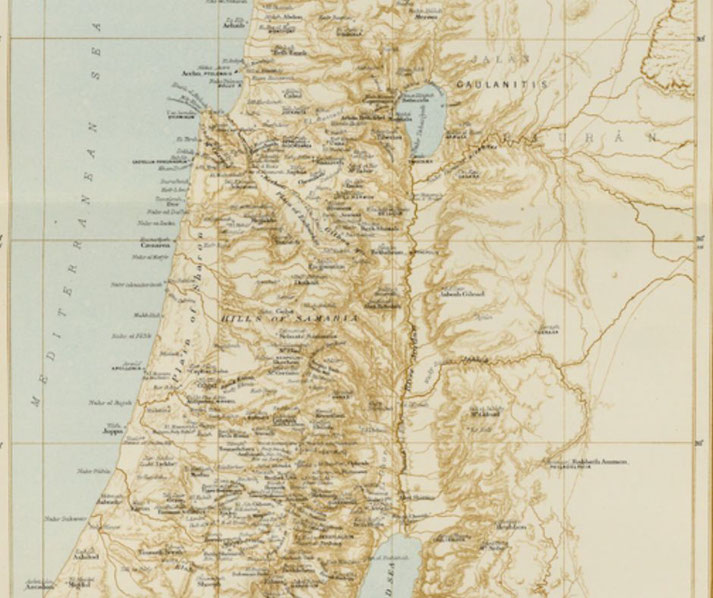

For thousands of years, the land historically known as Palestine experienced waves of migration and invasion that changed local authority over long periods of time.

The land, which lay at the junction of Africa and Asia, attracted merchants, armies, and religious pilgrims because of its religious importance and economic value.

The historical experience of the Palestinian people followed successive occupations. The population adapted through each regime change and maintained its cultural identity.

Who were the first people to live in Palestine?

Archaeological discoveries indicate that humans began to inhabit Palestine during the Epipalaeolithic and Neolithic periods, when early communities constructed permanent settlements and began to rely more on farming.

The Natufian culture, which ranged from around 12,500 to 9,500 BCE, were one of the earliest known examples of a settled way of life in the Levant.

Excavations at Tell es-Sultan, the site of ancient Jericho and one of the oldest continuously occupied cities in the world, uncovered mud-brick dwellings and evidence of stored grains that date to around 9000 BCE.

This suggests that agricultural societies had already replaced nomadic traditions.

Early domesticated crops included emmer wheat, barley, and lentils, which allowed for more stable food supplies.

During the third millennium BCE, the Canaanites established a series of city-states that included Hazor, Megiddo, and Jerusalem.

These urban centres built political institutions and religious temples while fostering busy markets connected to Egypt and Mesopotamia.

Canaanite scribes wrote in a Semitic language and passed on religious beliefs that later appeared in the Hebrew Bible, and their deities and rituals influenced the spiritual practices of neighbouring peoples.

The Ugaritic texts from the northern Levant give more detail about the mythology and religious practices that influenced early Canaanite life.

In the Late Bronze Age, Egyptian rule reached deep into Canaan, where pharaohs such as Thutmose III and Ramesses II controlled cities indirectly through local vassals.

The Amarna Letters, which were discovered in Egypt and are written in diplomatic Akkadian, describe how Canaanite rulers maintained loyalty to the Egyptian court while seeking protection from rival cities and nomadic raiders.

These records reveal a region that was politically divided but with active cultural life, and that remained under constant pressure from external powers.

Palestine under different ancient empires

In the 12th century BCE, new groups entered the region, including the Philistines, who arrived along the coastal plain and introduced iron tools, Mycenaean-style pottery, and new methods of agriculture and warfare.

Archaeological and genetic evidence suggests that they originated from the Aegean.

Their cities, such as Gaza, Ashkelon, Ekron, and Gath, became strongholds that frequently clashed with the Israelite tribes that emerged in the central highlands, and their rivalry features prominently in biblical narratives.

By the 10th century BCE, the Israelites had established the kingdoms of Israel and Judah, both of which built fortified cities and developed written records, religious centres, and royal administration.

Inscriptions such as the Tel Dan Stele and the Siloam Inscription provide historical evidence for political activity in Jerusalem and Samaria during this period, although both kingdoms faced repeated invasions and internal division.

Assyrian conquests in the 8th century BCE led to the destruction of the northern kingdom of Israel in 722 BCE, and the subsequent Babylonian invasion resulted in the capture of Jerusalem and the destruction of Solomon’s Temple in 586 BCE.

The Assyrians also implemented mass deportations under rulers such as Tiglath-Pileser III and Sargon II.

After the Babylonian exile, many Judeans returned under Persian rule, where the Achaemenid administration permitted religious reconstruction and local leadership, while Persian governors maintained overall authority in the region.

The edict of Cyrus the Great around 538 BCE allowed Jews to return and rebuild their temple in Jerusalem.

Under Persian administration, the population of Palestine became a mixture of Samaritans, Jews, Aramaeans, and other Semitic groups.

These communities lived in towns and villages across the region, and religious diversity remained a defining feature.

Despite being under imperial rule, local elites retained influence through temple leadership and land ownership, which allowed them to shape religious life and community identity.

Alexander and Rome

After Alexander the Great defeated the Persian Empire in the late 4th century BCE, his armies passed through Palestine and introduced Hellenistic practices that transformed urban life.

Following his death, his generals, known as the Diadochi, fought over control of the region, and eventually the Ptolemies of Egypt and the Seleucids of Syria divided influence over the eastern Mediterranean, including Palestine.

Key figures such as Ptolemy I and Seleucus I became the most important rulers of these competing dynasties.

During the 2nd century BCE, the Seleucid king Antiochus IV attempted to suppress Jewish religious customs and impose Greek practices, which sparked the Maccabean Revolt.

Led by the Hasmonean family, including figures like John Hyrcanus and Alexander Jannaeus, the rebels succeeded in regaining control over Jerusalem and established a dynasty that ruled parts of Palestine until the arrival of Roman intervention.

Their expansion brought new territories under Jewish rule, often through military conquest and forced religious conversion.

By 63 BCE, Roman general Pompey arrived in the eastern Mediterranean and made Palestine a client kingdom under Rome.

Herod the Great, who ruled under Roman patronage, undertook major building projects, rebuilt the Second Temple, and sought to maintain loyalty to Rome while suppressing local resistance.

His reign laid the foundations for further Roman involvement and direct rule.

Major building projects included Caesarea Maritima, the Herodium, and the fortress at Masada.

After Herod’s death, unrest grew, and a major Jewish revolt erupted in 66 CE. The Romans responded with overwhelming force, culminating in the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE.

A second uprising in 132 CE, which was known as the Bar Kokhba revolt and was led by Simon bar Kokhba, ended in devastation for the Jewish population.

In response, the Roman Emperor Hadrian renamed Judea as Syria Palaestina and forbade Jews from settling in Jerusalem, which they renamed Aelia Capitolina.

Palestine under Byzantine and early Islamic rule

With Christianity becoming the state religion of the Roman Empire in the 4th century CE, Palestine became a main center for Christian pilgrimage and religious discussion.

Byzantine emperors supported the construction of churches, monasteries, and religious schools, which attracted visitors from across the empire to sites associated with the life of Jesus.

Constantine the Great ordered the construction of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre around 326 CE, while Jerusalem, Bethlehem, and Nazareth grew in significance, and monastic life flourished in the deserts of Judaea.

While Christianity dominated religious life under Byzantine rule, the empire added more restrictions on Jewish and Samaritan communities, including bans on rebuilding the Temple and limited access to certain civic positions.

Religious disputes between Christian sects, particularly between Chalcedonians and Monophysites, added to social tension and sometimes led to violent confrontations within cities.

Arab Muslim armies that entered Palestine during the 630s under Caliph Umar defeated Byzantine forces and took control of Jerusalem without mass bloodshed.

Muslim rulers permitted Jews and Christians to practise their religions under the dhimma system, which required the payment of taxes but allowed religious self-governance.

The Pact of Umar later formalised these conditions. Over time, Arabic replaced Greek and Aramaic in administration and public life.

The Umayyad caliphs, who ruled from Damascus, constructed major religious buildings in Jerusalem, including the Dome of the Rock and the Al-Aqsa Mosque.

Later, under Abbasid and Fatimid rule, Palestine remained a region of mixed populations and religious activity, where towns such as Ramla, Hebron, and Tiberias served as centres where religious scholars taught and merchants exchanged goods while officials managed regional affairs.

Islamic, Christian, Samaritan, and Jewish communities continued to live in proximity, though often under different legal and social conditions.

The Crusades and Ayyubid Period

During the First Crusade in 1099, Latin Christian forces seized Jerusalem after a bloody siege that resulted in the slaughter of thousands of Muslim and Jewish residents.

The Crusaders established a series of fortified settlements throughout coastal Palestine and ruled through a feudal system that relied on European nobles and military orders to maintain control.

Baldwin I became the first king of the newly established Kingdom of Jerusalem.

Crusader rule disrupted traditional social structures and excluded local Muslim and Jewish populations from political power, although some Eastern Christians retained limited privileges.

The Kingdom of Jerusalem became a destination for pilgrims, but it also remained under constant threat from surrounding Muslim powers who sought to reclaim lost territory.

Castles such as Kerak and Belvoir Fortress illustrate the militarised nature of Crusader rule.

In 1187, Saladin, a Kurdish general and sultan of the Ayyubid dynasty, defeated the Crusaders at the Battle of Hattin and retook Jerusalem, which he entered peacefully.

Although he expelled Latin clergy, he allowed Christian pilgrimages to continue.

His policies encouraged the revival of Islamic institutions, including madrasas, mosques, and waqf systems, which strengthened Muslim presence in urban centres.

After Saladin’s death, internal rivalries and Crusader counterattacks disrupted the stability of the region.

However, the Mamluks eventually drove out the remaining Crusader enclaves by 1291.

Under Mamluk rule, Palestine became part of the Islamic world, and cities such as Nablus and Gaza played important roles in regional trade and religious scholarship.

Under Ottoman rule: Centuries of change and resistance

In 1516, Ottoman forces under Sultan Selim I defeated the Mamluks and incorporated Palestine into the Ottoman Empire, where it remained for the next four centuries.

The empire divided the region into administrative areas such as the sanjaks of Jerusalem, Nablus, and Gaza, each governed by officials who reported to the provincial authorities in Damascus.

Palestinian society during Ottoman rule consisted of Muslim agricultural communities, Christian merchants, Jewish religious centres, and nomadic Bedouin tribes.

Local notables, known as a‘yan, mediated between imperial authorities and rural populations, and their wealth often depended on land ownership and tax collection.

Figures such as Zahir al-Umar, who ruled much of Galilee in the 18th century, exercised considerable autonomy.

Jerusalem gained unique status as an autonomous district under direct imperial oversight due to its religious significance.

In the 19th century, reforms known as the Tanzimat introduced modern legal codes, new taxation systems, and changes to military conscription, which disrupted established power structures.

At the same time, European powers increased their influence through missionary work, consular protection of religious minorities, and archaeological exploration, often using religion as justification for political interference.

During the late Ottoman period, Jewish immigration increased due to the rise of the Zionist movement.

Organised Jewish settlers established agricultural colonies and bought land from absentee landlords, which led to growing resentment among Palestinian peasants who often lost access to fields they had farmed for generations.

Institutions such as the Jewish National Fund, established in 1901, and the World Zionist Organization facilitated land acquisition and settlement.

These developments contributed to the emergence of Palestinian political awareness and early resistance to land dispossession.

The British Mandate: An era of tension and transformation

Following World War I, Britain received the League of Nations Mandate for Palestine in 1920, after capturing the region from the Ottoman Empire.

The British had already issued the Balfour Declaration in 1917, which expressed support for a Jewish national home in Palestine.

Arab leaders, however, had understood that wartime promises made to them included independence in exchange for their support against the Ottomans.

Under British rule, Jewish immigration increased dramatically, particularly during the 1930s, as anti-Semitic persecution intensified in Europe.

The British facilitated land transfers and supported Zionist institutions, which allowed the Jewish community to develop autonomous structures, including schools and political organisations, alongside defence groups that managed community security.

Palestinian Arabs, facing economic hardship and political exclusion, organised a sequence of actions that began with strikes and protests and later escalated into armed resistance.

Key Arab leaders such as Izz ad-Din al-Qassam and Haj Amin al-Husseini became focal points for the resistance.

Between 1936 and 1939, the Arab Revolt erupted as a mass uprising against both British control and Zionist immigration.

Although British forces crushed the rebellion with military force and executed or exiled many Arab leaders, the revolt left a lasting impact on Palestinian society, including the erosion of traditional leadership and the rise of a younger, more radical generation.

In response, Britain issued the White Paper of 1939, which restricted Jewish immigration but failed to satisfy either community.

During World War II, British restrictions on Jewish immigration caused tension with Zionist groups, who began to resist British authority.

After the war, international sympathy for Jewish refugees increased, and the United Nations recommended the partition of Palestine in 1947.

The proposed plan, Resolution 181, granted 56% of the land to a Jewish state, 43% to an Arab state, and designated 1% (Jerusalem) as an international zone.

Palestinian Arabs rejected the division of their land and the loss of territory.

Therefore, who are the Palestinians?

As a result, the Palestinian people trace their roots to the many populations who lived in the region for thousands of years, including Canaanites, Aramaeans, Jews, Samaritans, Greeks, Romans, Arabs, and others who contributed to the cultural and religious life of the land.

Throughout each historical period, local communities preserved their identity through shared language and social customs, which reinforced their connection to towns and agricultural land.

The term ‘Palestinian’ was often used in a geographical sense, referring to inhabitants of the region without differentiating religious or ethnic background.

By 1948, Palestinian society included rural farmers, urban professionals, religious minorities, and political activists, all of whom considered themselves native to the land.

During the conflict surrounding the creation of the State of Israel, approximately 750,000 Palestinian Arabs were displaced, and more than 400 villages were destroyed or abandoned.

The resulting refugee situation did not erase their historical presence, which continues to form the basis of Palestinian political and cultural identity today.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.