The historical evidence for the existence of Moses

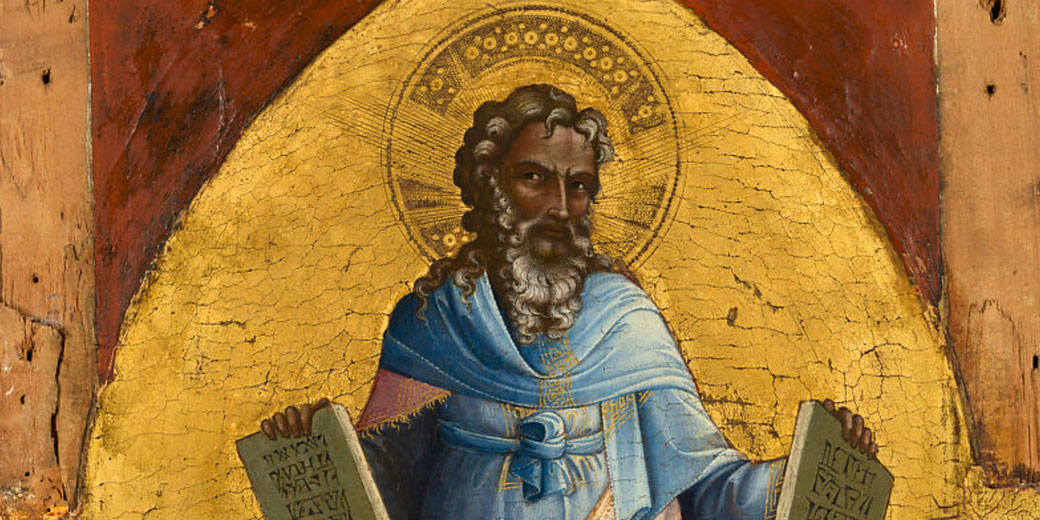

The person of Moses is a figure that is honoured in the religious traditions of Christianity, Islam, and Judaism, who regard him as the prophet who led the Israelites out of bondage in Egypt and received the divine law from God himself.

However, the historical reality of Moses and the Exodus event is a matter of heated debate, as scholars continue to search archaeological evidence and ancient texts for proof of his existence.

At this point in time, some argue for a historical core behind the biblical story, while and others maintain Moses is largely a legendary figure.

But what do we really know for certain?

The Late Bronze Age historical context

In the Hebrew Bible (also known as the Old Testament), Moses was a Hebrew child that was saved from the Egyptian Pharaoh that ordered his death, who was then adopted into the Egyptian royal household, and later chosen by God to free the Israelites from slavery (Exodus 1 to 3).

According to the biblical book of Exodus, after Moses confronted Pharaoh, a series of divine plagues struck Egypt and he then led the escape of approximately 600,000 Israelite men with their families from the land.

The story describes how the Red Sea parted before the wanderings of the Israelites in the desert for 40 years and then the covenant at Mount Sinai when Moses received the Ten Commandments, and ultimately his death before the Israelites enter the ‘promised land’ of Canaan.

The world in which Moses’ story is set, roughly the Late Bronze Age, circa 1550 to 1200 BCE, was ruled by strong kingdoms.

Egypt’s New Kingdom pharaohs held control over Canaan for much of this period.

They stationed troops there, and they managed major Canaanite towns. However, the biblical narrative never mentions Egyptian rule in Canaan during the Exodus or later Conquest of Canaan.

However, Egypt in the 18th and 19th Dynasties saw large building projects, including Pi-Ramesses in the Nile Delta, which seems to have employed forced labour.

Egyptian sources confirm that Semitic (“Asiatic”) populations were present in the Delta as slaves and workers.

In particular, the city of Avaris (modern Tell el-Dab‘a), which was the capital of the earlier Hyksos rulers, had a large Canaanite population.

Excavations at Avaris have revealed traces of Canaanite culture and even an early version of the unique four-room house, an architectural style typical of later Israelite villages.

Such findings indicate that people from Canaan lived in Egypt during this era, which is a likely setting for a group of Hebrews in Egypt.

Two historical periods have been proposed for a historical Exodus: an “early date” in the 15th century BCE, often linked to Pharaoh Amenhotep II if one accepts 1446 BCE for the Exodus, and a “late date” in the 13th century BCE, linked to Pharaoh Ramesses II or his son Merneptah.

The late-date view finds support in biblical references to the city of Ramesses and the appearance of Philistines who settled in Canaan only after circa 1200 BCE, and those details align with the 13th to 12th centuries.

Supporters of the early date refer to 1 Kings 6:1, which calculates 480 years from the Exodus to Solomon’s temple, and other biblical data to place the Exodus around 1440 BCE.

One firm date marker is the Merneptah Stele, an Egyptian victory inscription dated to circa 1207 BCE.

This stone monument set up by Pharaoh Merneptah records campaigns in Canaan and contains the earliest non-biblical mention of “Israel”: “Israel is wasted, its seed is not.”

The stele indicates that by the late 13th century BCE a people called Israel was present in Canaan as a social group probably in the central highlands.

While it says nothing about Moses or an Exodus, it gives the latest possible date for the Israelites’ arrival in Canaan.

In other words, any Exodus had to occur before 1207 BCE to allow Israel to be in Canaan by that time.

The details in the archaeological evidence

Archaeological evidence for Moses himself is hard to find, as one might expect for a nomadic leader without a grand tomb or palace.

There is no known inscription, statue, or object that directly bears the name Moses or confirms the biblical account of his deeds.

However, archaeology does provide indirect evidence that can be related to the Exodus saga, as well as limits on what could plausibly have happened.

Importantly, archaeologists highlight the silence of evidence for a mass migration of 600,000+ people across Sinai.

In fact, detailed surveys in the Sinai Peninsula have not clearly found traces of large campsites or regular occupation from the traditional Exodus period.

If upwards of two million people (the rough total implied by Exodus) wandered for 40 years, one would expect physical traces, such as pottery shards, food waste, or graves.

The clear lack of any such traces leads many to conclude that the Exodus as described likely did not occur in that form.

On the other side, archaeology does support key parts of the backdrop and possibility of a smaller Exodus scenario.

For example, New Kingdom Egypt was a multicultural empire that included many Asiatic slaves and servants.

A notable document known as Papyrus Brooklyn 35.1446 (13th Dynasty, ca. eighteenth century BCE) records the names of 95 household slaves in an Egyptian estate.

Over 40 of these names come from West Semitic (the language family including Hebrew), and several match specifically Hebrew names.

For example, one slave-woman’s name appears as Shiphra: the same name as Shiphrah, one of the Hebrew midwives in Exodus 1:15.

Another appears as Menahema, the feminine of the Hebrew name Menahem.

Although this papyrus comes before Moses (it dates to about 1700–1600 BCE, long before the traditional Exodus dates), it shows that people of Israelite or Canaanite origin lived in Egypt in significant numbers, even in noble households.

Furthermore, Exodus 5 describes that the Israelites had to make mud bricks, and Egyptian evidence clearly supports such practices.

In the tomb of Rekhmire, a Vizier of Egypt (c. 15th century BCE), wall paintings show foreign slaves who made bricks, while Egyptian overseers with rods supervise.

This scene dates to the time of Pharaoh Thutmose III and shows Semitic slaves engaged in brickmaking for state projects: exactly the kind of labor the Bible assigns to Hebrew slaves.

Additionally, an Egyptian leather scroll from the reign of Ramesses II lists quotas of bricks to be made by various overseers (each responsible for 2,000 bricks).

Papyrus records (Anastasi IV and V) even complain that “there are no men to make bricks and no straw,” which closely matches the Exodus story in which Pharaoh denies the slaves straw but demands the same quota of bricks.

These findings do not name the Israelites specifically, but they align with the social and economic setting shown in Exodus.

Traces of a 40-year nomadic journey for a whole nation are few, but that may not be surprising if the numbers were small, since nomadic and pastoral camps often leave little trace: temporary tents, wooden items, and minimal pottery might vanish.

Some scholars who claim historical accuracy note that one should not expect to find 'Hebrew campsites' easily.

They look instead at indirect clues like small-scale abandonments or ecological shifts.

For example, one hypothesis links the biblical Mount Sinai with a volcanic eruption (Thera’s explosion or others) that could explain certain “plague” phenomena, but this remains uncertain.

In this view, archaeology does not fully confirm or deny a smaller exodus. Scholarly estimates for a historical exodus group, if it occurred, range from a few hundred to a few thousand people, rather than millions.

Such a group might pass through the wilderness with minimal trace.

Also, if Moses led Israel out of Egypt and Joshua led them into Canaan, one would expect evidence of a sudden, forceful conquest of Canaanite cities around the Late Bronze–Iron Age transition (c. 1200 BCE).

Yet, the archaeological record shows different conditions. Major Canaanite cities like Jericho, Ai, and Hazor do show destruction layers, but their timing and conditions often do not match the biblical account.

Jericho, studied by Kathleen Kenyon, lay in ruin by the late 13th century BCE, so no fortified city stood to be conquered at Joshua’s time, since the walls collapsed centuries earlier.

Ai (identified with et-Tell) was uninhabited around 1200 BCE. Hazor was burned in the later 13th century, which might match Joshua’s narrative, but other evidence challenges a widespread conquest model.

Surveys reveal that around 1200–1100 BCE, hundreds of new small villages appeared in the highlands of Canaan.

These sites likely represent early Israelite settlements that local Canaanites formed when they adopted a new identity.

Some Egyptian influence appears, such as Egyptian-style jewelry or symbols, possibly due to long Egyptian occupation.

In short, Israel’s development looks more like social change within Canaan than the arrival of a nation from outside.

Ancient textual evidence outside the Bible?

Aside from the biblical narrative, what do other ancient records say about Moses or the Exodus?

Notably, no known inscription from Pharaonic Egypt directly mentions Israelite slaves, a mass exodus, or a figure named Moses.

This absence is not entirely surprising. Egyptian royal inscriptions were propagandistic and rarely, if ever, recorded defeats or embarrassments.

A successful slave revolt or the drowning of Pharaoh’s army would hardly be commemorated on temple walls.

That said, Egyptians did leave clues pertinent to the story’s background. One is the prevalence of Egyptian loanwords and names in the Exodus account.

For instance, the basket in which baby Moses was placed is called a tevat, which is a word of Egyptian origin (from dbjt) rather than standard Hebrew.

Also, the river (Nile) is called ye’or in Hebrew Scripture, a transliteration of the Egyptian term for the Nile, not the usual Hebrew word for river.

Even “Moses” (Moshe in Hebrew) is said to be named by Pharaoh’s daughter (Exod. 2:10), and scholars agree it derives from the Egyptian root msi (meaning “born of” or “child of”) found in names like Thutmose or Ramesses.

These linguistic footprints suggest the Exodus saga contains authentic Egyptian details, presumably preserved from the second-millennium setting.

An Egyptian compilation called the Onomasticon of Amenope (New Kingdom to Third Intermediate Period) even lists a Semitic toponym Per Atum (House of Atum) for a locale in the Wadi Tumilat region of the Delta.

This corresponds to Pithom (Pi-Atum), one of the store-cities the Israelites built. In addition, the Onomasticon shows that Semitic names for places were in use, hinting at a longstanding Semitic presence.

Even in Egyptian sources, the Semitic name for the Lakes of Pithom was used instead of the original Egyptian name.

Another Egyptian text often cited is the Admonitions of Ipuwer, a Middle Kingdom poem describing chaotic calamities in Egypt: the Nile turning to blood, darkness, and social upheaval.

These images have a striking resemble the Biblical plagues. Some have suggested Ipuwer’s text is a memory of real disasters that inspired the Exodus plagues.

However, mainstream scholars date Ipuwer to an earlier period (perhaps the Second Intermediate Period, centuries before Moses’ time) and view it as a literary genre describing general chaos rather than a reportage of specific events.

So, while tantalising, Ipuwer is not considered direct evidence of Moses or the Exodus by most experts.

One of the most intriguing ancient references comes from Manetho, an Egyptian priest-historian of the 3rd century BCE.

Manetho’s works survive only as quotations in later writers, especially the Jewish historian Josephus.

According to Josephus, Manetho told a story about a renegade Egyptian priest named Osarseph who led a rebellion of lepers and enslaved people, allied with foreign invaders, and briefly seized power in Egypt.

In this tale, set during Pharaoh Amenophis (sometimes identified with Amenhotep III or a fictional king), Osarseph institutes laws opposed to Egyptian religion (such as forbidding idol worship and sacrificing sacred animals) and fortifies himself at the former Hyksos capital, Avaris.

He invites the expelled Hyksos from Jerusalem to join his cause, and together they ravage Egypt until Pharaoh Amenophis and his son Ramesses muster an army and drive them out of the country.

Crucially, Manetho (via Josephus) says that Osarseph “changed his name to Moses” during these events.

This story is clearly a distorted echo of the Exodus that casts the leprous followers of Moses as villains who defiled Egypt.

Manetho essentially merges the Hebrews with the Hyksos and with a disease-ridden rebel force.

While not historically accurate in detail, it is significant that by the Hellenistic period Egyptian tradition remembered a figure named Moses associated with a exodus-like event.

Scholars like Jan Assmann interpret the Osarseph legend as a conflation of historical traumas (such as the Hyksos expulsion, the Amarna religious revolution under Akhenaten, etc.) reworked to explain the origin of the Jews.

Manetho’s account, written over a millennium after the purported events, cannot prove Moses’ existence; but it does show that the Exodus story made enough impact to warrant a counter-narrative in Egyptian lore.

Outside of Egypt, no contemporary Near Eastern texts mention Moses or an exodus.

One possible exception is a curious reference to a group called “the Shasu of YHW” in Egyptian records of the late 14th century BCE.

In a list of nomadic peoples defeated, Pharaoh Amenhotep III included “Shasu (nomads) of YHW”, which could be an abbreviation for a place or deity Yahweh.

Some scholars take this as evidence that the name of Israel’s God Yahweh was known in the region of Edom/Seir before the Israelites existed, perhaps indicating Midianite or Edomite worship of Yahweh that the Israelites later adopted.

In the biblical account, Moses indeed encounters Yahweh first in Midian (the Burning Bush on Mount Horeb/Sinai), and the Midianites are linked to Moses’ family.

This is a tenuous but intriguing hint that the Moses story might preserve a memory that Yahweh was originally a deity from the deserts south of Canaan.

What modern scholars believe about Moses

So where do modern scholars stand on the existence of Moses? Different academics range from staunch traditionalists, who accept Moses as a real historical leader of the Exodus, to extreme skeptics, who regard him as a mythical figure.

The majority position among historians and archaeologists today is somewhere in between: Moses may have been based on one or several real persons, but the biblical account is a theological narrative that has been influenced by centuries of oral tradition and later editors.

Here are the main arguments on each side of the debate and the nuanced middle ground.

Arguments for a historical Moses

It’s often noted that peoples and nations tend to mythologise victories, not defeats or humiliations.

The Exodus story is, at its core, a tale of slavery and wandering: a national humiliation to redemption narrative.

Proponents say it would be odd for Israelites to invent an embarrassing origin (as oppressed brick-makers and runaway slaves) unless it had some basis in memory.

They often accept that a literal reading of 600,000 men (2+ million people) is unrealistic.

Instead, they envision a much smaller group escaping Egypt. This removes the logistical improbability and the archaeological expectation of massive remains.

A band of, say, a few thousand Semitic slaves could escape without leaving clear traces, and Egypt might not pursue them vigorously or record the loss of a labor gang.

Egyptologists like James K. Hoffmeier and Kenneth Kitchen argue that in Egypt’s many records, missing a minor group of slaves is not surprising, especially if the event happened during a period of chaos or weak government control.

Some suggest the biblical numbers were inflated by later storytellers for theological reasons.

Therefore, if one reduces the scale, many problems (lack of archaeological evidence, logistical issues of feeding millions in a desert) become manageable.

However, a specific variant of the 'small Exodus' idea, championed by biblical scholar Richard Elliott Friedman, argues that only one tribe, the Levites, came out of Egypt and that Moses was principally the leader of this Levite exodus.

The Levites were later the priestly clan in Israel, and intriguingly, many Levite names are Egyptian (Moses, Aaron, Merari, Phinehas, etc.).

According to this theory, the Levites alone were former Egyptian slaves who joined with Canaanite Israelites in the highlands.

They brought with them the memory of deliverance, the worship of Yahweh, and distinct laws and rituals.

Over time, their story spread to all Israel and was adopted as national history. It would explain why Egyptian motifs permeate Israel’s religion (such as the tabernacle, ark, priestly vestments that have possible analogs in Egypt) and why only part of Israel (the Levites) had no land inheritance, since, perhaps they were a later immigrant group.

While not universally accepted, this hypothesis tries to reconcile the archaeological evidence of mostly indigenous origin with the possibility of a real Exodus group.

In comparison, a range of historical scenarios have been proposed to place Moses in a real context.

Some note that Pharaoh Ramesses II (1279–1213 BCE) built Pi-Ramesses in the Delta using slave labor, so an Exodus under his successor (Merneptah) during a time of distress (Merneptah faced Libyan invasions and crop failures) is conceivable.

Others prefer Amenhotep II (c. 1450 BCE) as the Pharaoh of the Exodus, since Egyptian records show he campaigned in Canaan but also that some Asiatics might have fled during his reign.

A few even associate Moses with the religious upheavals of Akhenaten (1350s BCE): Sigmund Freud famously hypothesized that Moses was an Atenist priest who, after Akhenaten’s fall, led followers out of Egypt, and carried with him monotheistic ideas.

This more fringe idea draws on the coincidence that Akhenaten’s monotheism predated Israel’s by just decades, but it lacks any real, concrete evidence.

Even the Hyksos expulsion (c. 1550 BCE) has been proposed as an inspiration, since Egyptian chronicles say the Hyksos were Semitic people expelled from Avaris and who went to Syria/Palestine.

At the very least, a number of respected scholars, though skeptical of details, believe there is a kernel of truth behind the Exodus.

The idea is that memories of small-scale escapes from Egypt, of oppressive conditions, and of a charismatic leader were preserved orally and then woven together.

Renowned archaeologist William F. Albright in the mid-20th century accepted Moses as historical and dated the Exodus to around the 13th century BCE; more recently, Egyptologist Kenneth Kitchen and James Hoffmeier have amassed what they consider cumulative evidence that the biblical account reflects second-millennium realities.

Arguments against a historical Moses

On the other side, many scholars question or outright reject the idea that Moses was a real historical individual in the way the Bible describes.

The simplest point is that there are thousands of Egyptian inscriptions, papyri, and administrative records from the New Kingdom period, yet none mention an Israelite community, the plagues, an exodus, or a leader named Moses.

If a catastrophe of Egypt losing a slave population and an army in the sea had happened, skeptics argue, it’s strange that it went unrecorded by Egypt’s neighbors and successors.

The counterargument about Egyptian silence on defeats is acknowledged, but even so, indirect evidence might be expected.

So far, none has been identified that unambiguously corresponds to Israel’s exodus.

In addition, Biblical scholars have long noticed that the Pentateuch (the books of Moses) contains signs of much later writing.

Linguistic analysis shows that parts of Exodus and Numbers use vocabulary and grammar from the first millennium BCE, not the second.

More tellingly, there are historical anachronisms: for example, the mention of Philistines in Exodus 13:17, “God did not lead them by the way of the land of the Philistines, though that was nearer”, is problematic if the Exodus happened before 1200 BCE, since Philistines settled in Canaan only after that date.

Similarly, references to Edom, Moab, and Ammon having established territories during Moses’ trek reflect the Iron Age reality (around 9th–7th centuries BCE) more than the Late Bronze Age.

This suggests the story (at least in its final form) was composed after Egypt’s empire had faded, possibly during the Babylonian Exile (6th century BCE) or Persian period.

According to this view, the figure of Moses could be a literary construct, amalgamating various leadership and lawgiver motifs to serve the exiled community’s need for a founding hero.

A strong consensus among archaeologists (sometimes called the “Canaanite origins” theory) holds that the Israelites emerged from indigenous Canaanite populations instead of from Egypt.

Extensive research in the highlands of Israel shows a cultural continuity from Late Bronze Canaanite society to early Iron Age villages that became Israelite.

The earliest Israelite material culture, such as pottery, architecture, and diet, is largely Canaanite, not something that arrived from outside (except for a notable absence of pig bones, perhaps indicating a new identity marker).

If the vast majority of Israel’s ancestors never left Canaan, the Exodus must have been marginal to their story.

Some scholars argue that the entire Exodus tradition was an invention of the later Israelite/Judean kingdom to provide a heroic origin and justify certain religious practices.

In this view, Moses is comparable to King Arthur in British lore, who was a possibly fictional leader around whom national legend coalesced. Such scholars see the Exodus story’s “memory” as deriving not from actual Bronze Age events but from later inspirations: perhaps the memory of being under foreign oppression (like the Babylonian exile) transposed into Egypt.

Other argue that the Moses we know is a composite of various motifs and sources.

The Pentateuch is traditionally thought to be woven from multiple documents (J, E, P, D in the Documentary Hypothesis), each with its own take on Moses.

One source might have emphasized Moses the miracle-worker, another Moses the lawgiver, another Moses the prophet.

Over centuries, these layers created an epic figure larger than life. Some elements of Moses’ story have clear folkloric parallels: the infant Moses placed in a basket on the river is remarkably similar to the earlier legend of King Sargon of Akkad, who, according to Mesopotamian lore, was cast adrift on the Euphrates as a baby and rescued.

For these skeptics, this legendary quality means Moses is not a datable, singular person but an embodiment of Israel’s collective experience and ideals.

The 'middle position' and ongoing debate

Between the poles of outright belief and outright denial lies a middle ground that many modern scholars occupy.

This view holds that the Exodus narrative is neither pure fiction nor straightforward history, but a mythologised history: a blend of real events, memories, and literary shaping.

Proponents of this middle view often hypothesize the following: at some point in the Late Bronze or early Iron Age, a group of Semitic slaves escaped from Egypt and had a profound encounter with a deity (Yahweh) in the wilderness.

They eventually joined with kin in Canaan, who had not been in Egypt, and shared their story of liberation.

Over generations, this story was adopted by all Israel as their defining narrative.

This would explain why the Exodus story resonates with themes of social justice (God hearing the cry of slaves) and why Pesach (Passover) became a central festival: it memorialised what was originally the experience of a subset of Israelites, elevated to national significance.

The key point is that something happened, significant enough to be remembered, even if we can’t reconstruct it fully.

Crucially, even if the Exodus story was finalized in the first millennium BCE, that doesn’t preclude that it contains older source material.

Scholars note that certain biblical poems, like the Song of the Sea in Exodus 15, may be very ancient.

Frank Moore Cross and David Freedman argued that the Song of Miriam (Exod. 15:21) and the victory song in Judges 5 date to the early Iron Age (circa 12th–11th century BCE).

If the Song of the Sea, which celebrates a victory over Pharaoh’s forces at the sea, is truly from that early period, it suggests a memory of an exodus was alive then.

Notably, that song does not mention Moses by name; it speaks of “the people” whom Yahweh redeemed.

This could imply that the core event was remembered, but the detailed role of Moses was fleshed out later.

Ultimately, from a historiographical perspective, many today adopt a cautious agnosticism about Moses.

They neither affirm his existence with certainty nor declare him pure fiction; rather, they admit the limits of evidence.

However, from the standpoint of cultural significance, whether or not Moses existed as described, the impact of the Moses story is real.

It galvanised a people’s identity in antiquity and continues to inspire millions today.

Throughout history, many nations have origin myths that are not 100% factual yet carry profound truth for those who tell them.

The story of Moses and the Exodus may be one such case.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.