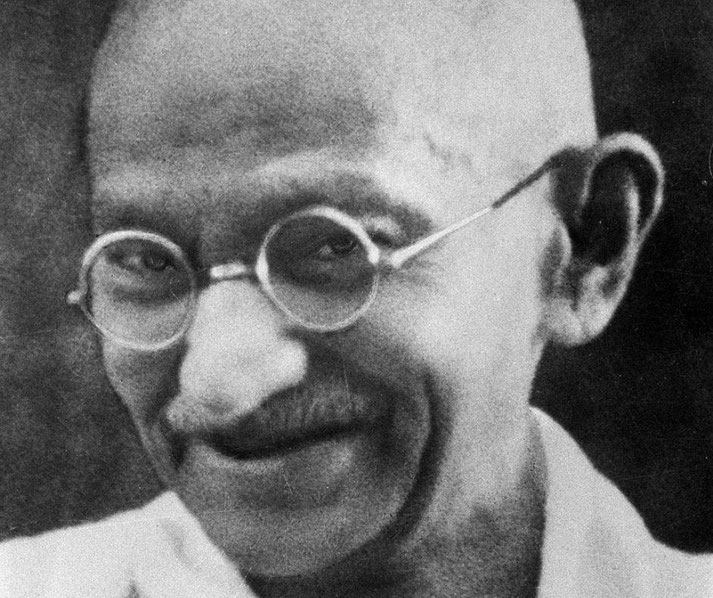

Why Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated in 1948

On the 30th of January 1948, the 78-year-old Mahatma Gandhi was suddenly shot three times while on his way to an evening prayer meeting in New Delhi.

Gandhi collapsed and was carried into the house, but died soon after. The news of his death shocked the world and, in a radio address to the nation, Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru sorrowfully announced, “the light has gone out of our lives”.

But why was one of the most revered advocates for peace assassinated, and who was responsible?

The Partition and the growing communal tensions

Just a few months before that fateful day, in 1947, India and finally achieved independence and the Partition from Britain.

As part of this process, the subcontinent had been divided into two states: Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan.

Sadly, this had also been accompanied by horrific communal violence from clashes between Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs that led to an estimated loss of around one million lives, with another 12–20 million people displaced from their homes.

This deeply traumatised both of the new nations and created intense religious and political tensions.

Gandhi, who was a devout Hindu, and who preached non-violence and Hindu-Muslim unity, had worked tirelessly to stop the various outbreaks of communal rioting.

In late 1947 and early 1948, he had undertaken a series of hunger strikes in some of the most troubled cities like Calcutta and Delhi.

He hoped that it would persuade communities to stop the killing.

Sadly, not everyone in India agreed with Gandhi’s approach. Some Hindu nationalist groups were very angered by Partition and believed that Hindus had been blatantly wronged.

As a result, they resented Gandhi’s influence in government policies and his attempts to accommodate India’s Muslim minority.

In their view, India should have been declared explicitly a Hindu nation immediately after independence, and they saw the creation of Pakistan as a failure of Gandhi’s vision.

During the 1940s, an ideological conflict flared between those who supported Gandhi’s inclusive, secular nationalism and those who preferred Hindu control.

Since Gandhi was seen as a champion of inter-religious harmony, he was seen by some as an obstacle by extremist elements on the Hindu right.

Who was Nathuram Godse?

One of the most right-wing Hindu nationalist organisations was known as Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (or RSS).

One of its former members would become a key figure in the attack on Gandhi. His name was Nathuram Godse.

By January 1948, Godse had grown convinced that Gandhi’s political influence was harming India and the Hindus in particular.

During his later trial, Godse gave a lengthy explanation for what he was going to do.

In it, he outlined the fact that since Gandhi had supported the partition of India, which Godse believed led to the suffering and displacement of millions of Hindus from Pakistan, Gandhi did not do enough to prevent the massacres of Hindus and Sikhs during the Partition riots.

He felt that Gandhi had remained too lenient even as Hindus were being killed or forced to flee from areas that became Pakistan.

Also, Godse accused Gandhi of appeasing the Muslim community and the leaders of the Muslim League (the party that had demanded the creation of Pakistan).

He was especially enraged that in January 1948, Gandhi undertook a fast to pressure the Indian government to release a payment of funds to Pakistan that had been frozen during the India-Pakistan war in Kashmir.

Due to this pressure, the Indian government did reverse its decision and paid the money to Pakistan.

To Godse, this confirmed that Gandhi wielded undue influence, and the government was “running by Gandhi’s whims” rather than the national interest.

As such, Godse saw Gandhi putting Pakistan’s needs above India’s.

What is more, although Gandhi preached non-violence and religious harmony, Godse saw these teachings as naive in the face of violent threats.

He believed that Gandhi’s insistence on non-violence would only invite further aggression.

In Godse’s opinion, Gandhi’s calls for Hindu-Muslim unity meant that Hindus were constantly asked to tolerate and forgive, even when they were under attack.

He felt this put Hindus at a disadvantage and ‘betrayed’ Hindu interests. Godse argued that forceful retaliation was sometimes necessary to protect the nation, and that Gandhi’s removal would make India more secure and assertive.

He stated openly that he admired Gandhi as a person, but he saw Gandhi’s political influence as disastrous for India’s future.

Who else was involved?

Godse did not act entirely on his own, as there would be a conspiracy by a small group of other extremist Hindu nationalists.

One of them was Narayan Apte, who was Godse’s close associate and who helped organise the plot.

In total, eight men would be tried for the conspiracy to murder Gandhi, including Gopal Godse (Nathuram’s brother), Madanlal Pahwa, Vishnu Karkare, Shankar Kistayya, Dattatraya Parchure, and Digambar Badge.

Most of these men were, like Godse, members or volunteers of Hindu nationalist organisations.

The conspirators had actually made a failed attempt to kill Gandhi earlier on 20 January 1948.

In that earlier attempt, one plotter threw a bomb at Gandhi’s prayer meeting, which exploded but did not harm Gandhi.

The attackers fled, but one was caught. This did not deter Godse’s group, however; they regrouped and struck again ten days later.

What happened on the day of the assassination

On 30 January 1948, Mahatma Gandhi was staying at Birla House in New Delhi, as he often did when in the capital, and every evening, he led a prayer meeting in the gardens, which attracted hundreds of visitors.

On this particular afternoon, Gandhi met with important political leaders to discuss India's tensions with Pakistan and the ongoing efforts to bring peace after Partition.

At the time, his health was increasingly fragile. He had recently ended a fast to persuade rioters to stop communal violence in Delhi.

He was weak and had to be assisted when walking.

At about 5:00 pm, Gandhi left his room to go to the prayer meeting, supported by his two grandnieces, Abha and Manu Gandhi.

As they crossed the gardens toward the prayer ground, a small crowd gathered along the path.

It must be noted that Gandhi often refused police protection because he insisted that he must remain accessible to the people.

As Gandhi reached the clearing, Godse stepped out of the crowd. He bowed respectfully in the traditional Hindu manner and then quickly drew a small, semi-automatic pistol from his clothes.

At close range, Godse fired three shots into Gandhi’s chest and abdomen. Gandhi fell to the ground and reportedly murmured "Hey Ram" (O God), though some witnesses later disputed whether he spoke at all.

The people nearby immediately seized Godse and beat him severely before the police arrived and took him into custody.

Gandhi himself was hurriedly carried back into Birla House, but he had already died from his wounds.

Within minutes, news of the assassination spread through Delhi, while Jawaharlal Nehru was informed almost immediately.

Gandhi's funeral took place the following day.

Immediate aftermath and the impact on India

People of all communities, whether Hindus, Muslims, or Sikhs, mourned together and the widespread rioting finally subsided, in part because the country was united in grief and disbelief.

As a result, the assassination effectively ‘ended’ the frenzy of killings. Gandhi’s funeral procession in Delhi was attended by an enormous crowd of people from all walks of life, while his ashes were carried across India by train so that ordinary people could pay respects.

This elevated Gandhi’s status even further as a national hero who had sacrificed his life for peace.

Furthermore, the government took swift action against the organisations perceived to be linked to the assassination.

In February 1948, the RSS was banned by the Indian government, and about 20,000 RSS members were arrested within the following months.

The Hindu Mahasabha, while not officially banned, became politically stigmatized and lost much of its influence due to public anger.

Many Indians now viewed the Hindu extremist ideology with revulsion, since it had been associated with the killing of Gandhi.

Even though only a small group of men carried out the murder, their actions cast a negative light on the broader Hindu nationalist movement for years to come.

In the months after the assassination, Indian leaders decisively rejected the idea of making India a religion-defined nation.

The implication of the Hindu right wing in Gandhi’s murder discredited calls to turn India into a 'Hindu state.'

Instead, leaders like Prime Minister Nehru pushed even harder to ensure the new Republic of India would treat all citizens equally, regardless of religion.

Historians note that this would be reflected later in the Indian Constitution of 1950, which officially established India as a secular democratic republic.

Although, it must be noted that there were some instances of backlash. In parts of India, especially in Maharashtra (where Godse was from and where many Chitpavan Brahmins lived), angry crowds targeted members of the Brahmin community in retaliation.

The Chitpavan Brahmins, a community to which Godse belonged, had prominent members in the Hindu nationalist movement.

After Gandhi’s assassination, some of their homes and properties were attacked by outraged fellow citizens.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.