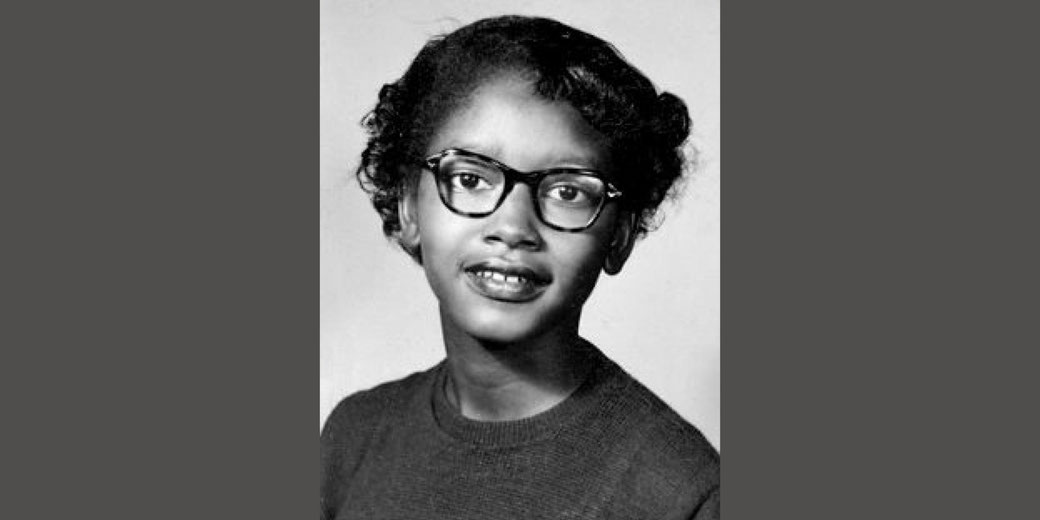

Claudette Colvin: the forgotten teenager who said 'no' before Rosa Parks

On 2 March 1955, a fifteen-year-old Black student in Montgomery, Alabama, refused to give up her seat to a white passenger.

Her name was Claudette Colvin. She had recently learned about the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling in class, and she could readily quote the Bill of Rights from memory.

That day, she had firmly believed she had the law on her side and chose to act on principle. Her decision came nearly nine months before Rosa Parks made a similar stand, yet civil rights leaders largely left Colvin out of the public story. Why?

Her early life

Claudette Colvin, who was born on 5 September 1939, grew up in King Hill, a predominantly Black neighbourhood with limited resources on the western edge of Montgomery.

Her biological parents were C.P. Colvin and Mary Jane Gadson, who could not afford to raise her at the time, so she moved in with her great-aunt and great-uncle, Mary Jane and Q.P. Colvin, who gave her a relatively stable home and insisted on good behaviour and firm moral values.

At school, Colvin had consistently proved intelligent and eager to learn. She had attended Booker T. Washington High School, one of the few Black high schools in Montgomery, where her teachers had regularly urged their students to understand Black history and take pride in their heritage.

One teacher was Miss Geraldine Nesbitt, who had regularly taught her to memorise the key freedoms promised in the United States Constitution.

Another was Miss Jo Ann Robinson, who had actively encouraged students to believe that young people had a duty to challenge injustice through peaceful resistance.

Robinson would later help organise the Montgomery Bus Boycott as part of the Women’s Political Council.

For instance, Colvin had often spoken of Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth, whom she had called personal heroes.

She had also taken an interest in current legal debates, particularly the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, which she had interpreted as a signal that segregated spaces were no longer legally valid.

That understanding stayed with her when she boarded the bus in March 1955.

Experience of daily racism

During her childhood, Colvin had lived under the strict rules of Jim Crow segregation where public services, schools, water fountains, restaurants, and buses had all reinforced a racial hierarchy.

Black residents could not challenge a white person without risking violence, arrest, or loss of employment.

On Montgomery’s buses, white passengers had sat at the front, and Black passengers had sat at the back.

If the front section filled, the driver would force Black passengers to give up their seats.

That meant that the law did not allow physical mixing, even if seats remained available.

Colvin had seen this happen repeatedly and understood the consequences of disobeying an order from a white driver.

Drivers like James Blake, who later ordered Rosa Parks off his bus, had frequently carried firearms and had enforced segregation by threatening people.

At the time, her teachers had regularly encouraged students to stay informed about national legal decisions.

After Brown v. Board, Colvin had believed that the logic of that case should apply to all public segregation.

As a result, she had believed that the Constitution promised her dignity and legal protection.

She had also known that roughly 75 percent of Montgomery’s bus riders were Black, yet they had no representation or protection.

By then, Colvin had begun to speak more openly about her views. She had criticised the way Black citizens were treated on buses.

Dramatic day of her arrest

On 2 March 1955, Colvin boarded a Capitol Heights bus on her way home from school and sat in the first row behind the seats reserved for white passengers.

When a white woman boarded and needed a seat, the driver, Robert W. Cleere, ordered Colvin and three other Black passengers to move.

Two complied immediately, and one moved reluctantly. Colvin refused.

She told the driver that she had paid her fare and had a right to keep her seat. The driver warned her again, then called the police, and when the officers arrived, they demanded she move.

Colvin just repeated her claim that the Constitution protected her position. The officers pulled her from the seat, grabbed her schoolbooks and handbag, and took her to the station.

She later recalled, "All I remember is that I was not going to walk off the bus voluntarily."

Soon after, authorities promptly took action by charging her with disturbing the peace and accusing her of breaking city segregation laws, and prosecutors later claimed that she had assaulted a police officer.

She had denied all of them. At the station, she said that the officers had treated her roughly and had humiliated her.

Her mother, who had heard what happened, came to pay her bail and take her home.

News of her arrest had spread quickly and widely through Montgomery’s Black community.

While many had admired her bravery, others had initially feared that the incident would attract unwanted attention or bring retaliation.

Leaders in the NAACP considered using her case to challenge bus segregation but initially hesitated due to her age and the seriousness of the assault charge.

Her day in court

On 18 March 1955, Colvin appeared in juvenile court, where Judge John B. Scott heard the case.

Her defence lawyer was Fred Gray, who argued that she had acted peacefully and had been within her legal rights.

However, the prosecution insisted she had broken the law and disobeyed police officers.

In the end, the judge dropped the segregation charge but convicted her of disturbing the peace and assault, and the court placed her on probation because that meant she avoided jail and was left with a record.

The outcome disappointed some supporters who had hoped her case might lead to a legal breakthrough.

As a result, NAACP officials had initially decided not to make her the centre of a legal campaign, since some had worried that her conviction and her working-class background would draw negative attention.

Others believed that a more established figure with a steady job and no complications would have a better chance of winning public sympathy.

Nevertheless, Colvin had eventually played a key role in Browder v. Gayle, the case that struck down bus segregation in Montgomery.

In 1956, she joined three other women, Aurelia Browder, Susie McDonald, and Mary Louise Smith, who served as plaintiffs, and her testimony ultimately helped the federal court rule on 13 November that the city’s bus system violated the Constitution.

The Supreme Court upheld that ruling on 17 December 1956, and the legal end of segregated buses in Montgomery took effect shortly afterwards.

Her life after the court case

After the trial, Colvin had returned to school but had found herself increasingly isolated as some classmates supported her and others avoided her.

Some adults in her neighbourhood had expressed concern, and job opportunities in Montgomery had become difficult to find.

She had a child in March 1956, which likely added to the perception among civil rights leaders that she no longer suited their image of a test case.

Eventually, she moved to New York City, where she later attended nursing school in Manhattan before settling in the Bronx, where she worked as a nurse’s aide at a retirement home.

She held that job for more than thirty years. During that time, she had rarely spoken publicly about her role in the civil rights movement, as few people outside her immediate family even knew what she had done.

Her mother once told her, "Let Rosa be the one. White people aren’t going to bother Rosa. They like her."

Decades later, scholars began to re-examine her story as authors and filmmakers gradually began to include her name in books and documentaries, and journalists started to examine her impact in newspaper articles.

In 2009, the state of Alabama issued a resolution to acknowledge her contributions and, in 2021, a judge formally expunged her record after legal efforts by her supporters.

In recent years, she has received invitations to speak and attend commemorations.

However, the long delay in recognition had left her with mixed feelings. She has publicly expressed pride in what she did and regret that the movement kept her out of the public story.

Her story reminds historians that civil rights change often depended on many people who acted without reward or recognition.

Her comparisons with Rosa Parks

Both Claudette Colvin and Rosa Parks refused to give up their seats on Montgomery buses, and both faced arrest for disobeying segregation laws.

Yet Parks became the public figure chosen to symbolise the cause. She had served as secretary of the Montgomery NAACP, worked in a steady job, and had an established reputation in the community.

At the time, civil rights leaders generally believed they needed someone who had an impeccable public image.

Colvin was intelligent and brave, had legal troubles, and relatively soon became a single mother.

That fact made some leaders fear that the press would use her personal life to discredit the movement’s aims.

Still, Colvin’s earlier action laid the foundation for the boycott and the legal battle that followed as her involvement in Browder v. Gayle brought an end to bus segregation in the courts and changed practices on the streets.

While Parks became the icon, Colvin helped deliver the legal victory.

For many years, textbooks and documentaries left her name out of the story, and that silence has slowly begun to change.

Her defiance had largely grown from legal lessons taught by committed teachers and from a firm personal conviction, and it gave the civil rights movement one of its earliest examples of student protest.

Her story arguably belongs among the first sparks that lit the struggle for racial justice in America.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.