Why was Abraham Lincoln assassinated?

On the night of 14 April 1865, just days after the surrender of the Confederate Army at Appomattox, President Abraham Lincoln attended a performance of Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C.

He took his seat in the presidential box beside his wife Mary Todd Lincoln, unaware that an armed attacker had already slipped into the building.

John Wilkes Booth, a well-known actor and supporter of the Southern cause, crept up behind the president and fired a pistol into the back of his head.

But why did he do it?

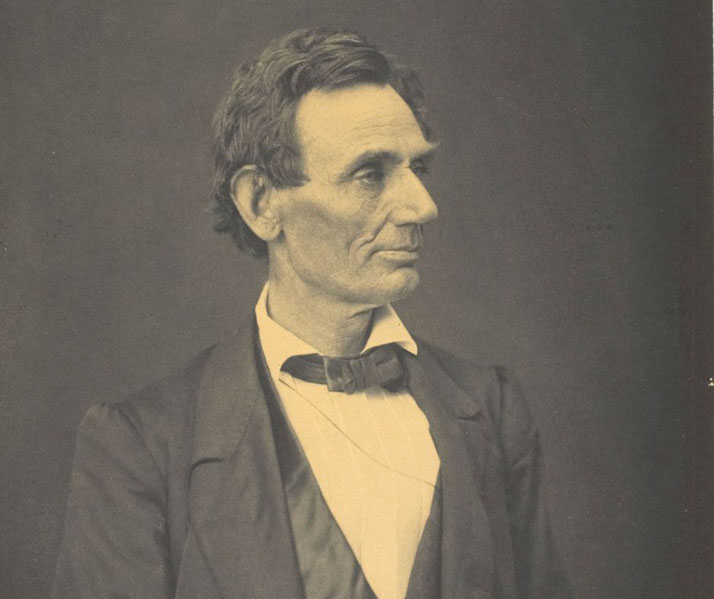

The remarkable life of Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln was born on 12 February 1809 in a log cabin in Hardin County, Kentucky, in an area that later became LaRue County in 1843.

He spent much of his early life working on farms in Indiana and later in Illinois. His family lived in poverty, and he received little formal schooling, but he read constantly and developed a strong interest in law and politics.

During the 1830s, Lincoln entered public life by serving in the Illinois State Legislature.

He later won a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1846 and returned to law after one term.

In the years that followed, Lincoln re-entered politics as national debates over slavery became more urgent.

His firm opposition to the expansion of slavery helped him gain widespread notice during the 1858 debates with Senator Stephen Douglas.

In 1860, the Republican Party selected Lincoln as its presidential candidate. His victory in the election caused immediate alarm in the South, where many feared that his policies would threaten the institution of slavery.

Several states seceded before he even took office, and Lincoln faced the collapse of the Union from the beginning of his presidency.

During his time in office, Lincoln focused on keeping national unity while also dealing with the urgent issue of slavery.

On 1 January 1863, he issued the Emancipation Proclamation, with the result that enslaved people in rebel-held areas were declared free.

He also supported the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, which aimed to abolish slavery throughout the United States.

In his second inaugural address in March 1865, he called for an effort to bring peace expressed as the war drew to a close.

The bloodshed of the Civil War

The Civil War began in April 1861 when Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumter in South Carolina.

Lincoln responded with a call for volunteers to defend the Union, and the country entered a brutal conflict that lasted for four years.

From the outset, Southern leaders claimed they fought to defend the rights of states.

However, the survival of slavery formed the foundation of their demands. Lincoln understood the connection between secession and slavery, and he worked to make the war a fight for national unity and human freedom.

In 1862 and 1863, Union victories at Antietam and Gettysburg began to shift the course of the war.

Generals like Ulysses S. Grant and William Tecumseh Sherman used forceful tactics that wore down the Confederate military.

In early 1865, General Robert E. Lee’s army broke down under constant pressure, and on 9 April, he surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House.

Throughout the conflict, the death toll reached extreme numbers. Recent estimates place the number of soldiers who died at around 750,000, and countless civilians endured hunger, illness, as well as displacement from their homes.

Many towns and farms in the South lay in ruins, and economic recovery appeared uncertain.

As the war ended, Lincoln promoted a balanced approach to Reconstruction, because he wanted to heal divisions without humiliating the former Confederacy.

John Wilkes Booth and the plot against Lincoln

John Wilkes Booth, who was born in 1838 in Maryland, gained fame as a Shakespearean actor but developed loyalty to the South.

He viewed Lincoln as a destroyer of traditional freedoms, claiming Lincoln had ignored the Constitution and favoured African Americans.

In private, he expressed admiration for the Confederacy and hatred for the Union’s leadership.

However, Booth kept secret ties with Confederate operatives, who included contacts in Canada and had discussed plots that might influence the war.

In March 1865, Booth planned to kidnap Lincoln and force the Union to release Confederate prisoners.

He gathered a group of co-conspirators, including Lewis Powell, George Atzerodt, David Herold, and Mary Surratt.

They plotted to capture the president and hide him in the South, with the aim of exchanging him for thousands of captured soldiers.

That plan failed when Lincoln’s travel schedule changed without notice.

Following the Confederate surrender in April, Booth decided to carry out assassination instead.

He hoped that killing Lincoln, Vice President Andrew Johnson, and Secretary of State William Seward would cripple the government and revive Southern resistance.

He assigned specific targets to each member of the group and set the attack for the night of 14 April.

Motivated by radical political beliefs and racial prejudice, Booth believed that Lincoln’s death would avenge the South and halt the expansion of Black civil rights.

He had been present during a speech in which Lincoln expressed support for limited Black voting rights.

That statement convinced Booth that he had to act before Lincoln could further advance racial equality in the United States.

How Lincoln was killed

Lincoln and his party arrived at Ford’s Theatre around 8:30 p.m. They were seated in the presidential box, where a guard named John Frederick Parker had been assigned, but he was absent at the time of the attack.

Booth entered the theatre freely and moved toward the president’s position without being challenged by anyone.

At around 10:15 p.m., Booth fired a single shot from a small Derringer pistol into the back of Lincoln’s head.

The sound of the gunshot shocked the audience, though many believed it was part of the play.

Lincoln fell forward in his seat, unconscious.

Major Henry Rathbone attempted to stop Booth, who used a dagger to slash Rathbone’s arm before leaping over the railing.

The box had been covered with flags, one of which Booth snagged as he leapt from the railing.

As he landed clumsily on the stage, he had broken his left leg: an injury he later claimed occurred during the fall, though some historians believe it may have happened later.

Booth shouted “Sic semper tyrannis” and fled through a side exit. Panic spread among the crowd as some people screamed, others rushed for the exits, and many stood frozen in disbelief.

Doctors rushed to Lincoln’s side and decided that his wound needed to be treated elsewhere because the theatre lacked the proper equipment.

They carried him to a boarding house across the street and placed him on a bed too small for his height.

Throughout the night, medical staff stayed with him, but the injury proved fatal. At 7:22 a.m. on 15 April, Lincoln died in silence.

The hunt for the killers

Booth escaped into Maryland, where he reunited with David Herold. The two travelled south and stopped at the home of Dr Samuel Mudd, who set Booth’s broken leg.

They then continued into rural Virginia, hiding in wooded areas and barns as Union troops closed in.

In the meantime, Lewis Powell carried out a violent attack on Secretary of State Seward, who was recovering from a previous injury.

Powell forced his way into the house, stabbed Seward and several others, and then fled into the night.

Seward survived, although he was badly hurt. George Atzerodt chose not to attack Johnson.

Authorities responded swiftly to the attacks and arrested several individuals thought to be involved.

The War Department offered a reward of $100,000 for Booth’s capture. In total, more than 10,000 federal troops, detectives, and local police took part in the manhunt.

On 26 April, Union troops surrounded a barn on the Garrett family’s farm near Port Royal, Virginia.

Booth and Herold had taken shelter there, as they looked for a way to travel farther south.

Herold surrendered without fighting back, but Booth refused to leave the building.

So, the soldiers set the barn on fire, and Sergeant Boston Corbett fired a single shot that struck Booth in the neck.

He died shortly afterward. Some accounts report his final words were “Tell my mother I die for my country,” while others claim he whispered “Useless, useless,” which is the version most commonly believed by people who were there.

Mary Surratt, whose boarding house served as a meeting place for the conspirators, was arrested and later convicted alongside Powell, Atzerodt, and Herold.

All four were hanged on 7 July 1865. Surratt became the first woman executed by the U.S. federal government.

The military tribunal that sentenced her drew criticism and is still argued about.

How America mourned for Lincoln

Soon after the president’s death, people began to grieve deeply. Church bells rang across the Northern states, and public buildings were covered in black cloth. Citizens gathered in the streets.

Businesses closed. Streets emptied, church bells tolled, and families stayed home, uncertain about what would come next.

Lincoln’s body lay in state at the Capitol before beginning a long funeral journey.

The train that carried him back to Springfield, Illinois, followed a route that closely looked like the one he had taken to Washington four years earlier.

One of the cars, named the "United States," was covered with black cloth and became a sign of how deeply the country was mourning.

Large crowds gathered in cities such as Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York, Cleveland, and Chicago, and some people stood by the tracks, holding candles as the train moved through the city at night.

Among the mourners were thousands of newly freed African Americans. They saw Lincoln as the president who had given them hope for a different future.

Many waited for hours to view his casket or join quiet ceremonies held in his honour.

Also, Union veterans stood in silence, some of whom still had injuries from fighting in the war, while families who had lost husbands, brothers, or sons gathered nearby.

Lincoln’s burial in Springfield took place on 4 May 1865. Vice President Andrew Johnson had assumed the presidency and accepted the hard work of putting the country back together.

In Lincoln’s absence, Radical Republicans eventually overpowered Johnson's resistance and took control of postwar decisions, causing serious arguments in Congress and triggering years of political tension in national politics.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.