Valley of the Kings: where Egypt's most powerful pharaohs hid their enormous wealth

Once the centre of royal burial tradition in New Kingdom Egypt, the Valley of the Kings was a carefully selected burial site where pharaohs and nobles were interred with extraordinary riches.

Positioned in a remote desert gorge on the west bank of the Nile, the site held deep religious importance which was linked to the setting sun and the cycle of rebirth.

Its isolated terrain, hidden within the limestone cliffs opposite ancient Thebes (modern Luxor), offered both spiritual meaning and practical protection.

Its secretive location

Beyond the western cliffs of Thebes, the Valley of the Kings occupied a naturally sheltered area in the desert.

The barren, sun-scorched hills hid the entrances to dozens of tombs carved into the bedrock.

The west bank of the Nile symbolised the land of the dead, and the valley itself lay beneath the peak of al-Qurn, a pyramidal mountain that echoed the shape of Old Kingdom tombs.

Egyptian priests and royal architects saw this shape as a sacred sign that aligned with the solar theology of the time.

They also associated al-Qurn with the cobra-headed goddess Meretseger, believed to guard the necropolis.

Guards stationed at various vantage points along the cliffs watched for any sign of intrusion.

Tomb entrances were intentionally built into the ground and hidden from plain view.

No large structures marked their locations. Paths that led to the tombs twisted between narrow gorges, which provided natural concealment.

The valley's isolation from nearby settlements limited the number of people who could access the tombs during construction and burial rituals.

Pharaohs hoped this would protect their wealth from robbers and ensure their eternal life through undisturbed burial.

The nearby village of Deir el-Medina housed the artisans who carved and decorated the tombs, and strict secrecy controlled their lives to prevent leaks of tomb locations.

When were the tombs built?

Most of the tombs in the Valley of the Kings were constructed during the New Kingdom period, which lasted from approximately 1539 to 1075 BCE.

The earliest royal tomb is traditionally attributed to Thutmose I of the 18th Dynasty and was cut around 1500 BCE, although some scholars suggest that Amenhotep I may have been the first king buried in the valley.

Successive pharaohs followed this model, including Thutmose III, Amenhotep III, and the rulers of the Ramesside period.

Tomb KV17, belonging to Seti I, became one of the most extensively decorated examples and is also the longest tomb in the valley, extending more than 130 metres.

Tomb construction often began shortly after a pharaoh's coronation and continued throughout his reign.

The time available for building directly influenced the size and complexity of the tomb.

Ramses II, who ruled for 66 years, had one of the most detailed tombs, while kings who died young, such as Tutankhamun, were buried in much smaller chambers.

His tomb may have originally been intended for a non-royal individual and was reused after his sudden death. Some tombs were abandoned mid-construction when a king died unexpectedly.

In total, over 60 tombs were dug across the 18th, 19th, and 20th dynasties, each one designed to house the physical remains alongside treasure while embedding defences believed essential for securing the soul in the afterlife.

During the Third Intermediate Period, priests transferred royal mummies from their original tombs to hidden storage areas, such as DB320 and KV35, in an effort to protect them from looting.

The incredible tomb designs

Most tombs followed a similar architectural plan: a long descending corridor leading to an antechamber, followed by one or more burial chambers deep within the rock.

Side rooms for storage branched off the main corridor. Some tombs extended over 100 metres into the hillside and reached depths of 30 metres or more.

Tomb axes were often aligned east to west to symbolise the sun's nightly journey through the underworld.

Tomb builders carved shafts and false doors to confuse potential robbers. The architecture of the tomb symbolised the journey of the sun god Ra through the underworld.

Long passages represented the hours of the night, and the innermost chamber served as the divine resting place.

Stone doors were fitted, niches were left for statues, and alcoves were created for ritual objects.

In the larger tombs, columns and vaulted ceilings added a sense of grandeur to the subterranean spaces.

Builders sketched plans using red and black ink directly onto walls, guiding the placement of decorative scenes.

How the tombs were decorated

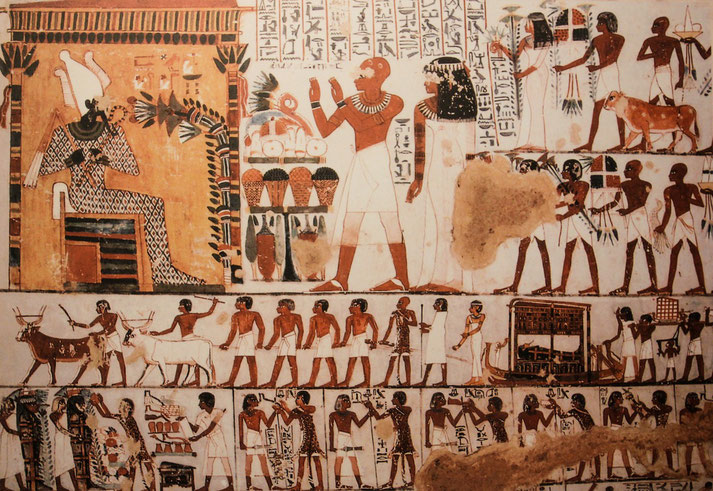

Painters and sculptors adorned the tombs with intricate carvings and vivid wall paintings.

Scenes depicted gods, demons, protective spells, and the deceased king undergoing judgement before Osiris.

Artists followed detailed funerary texts, such as the Amduat, the Book of Gates, and the Book of the Dead, to guide the king's soul through the perils of the underworld.

These texts were often arranged in a strict order on the walls, starting near the entrance and ending in the burial chamber.

Common motifs included Anubis overseeing embalming rituals and the weighing of the heart against the feather of Ma'at.

Pigments were made from natural minerals, including ochre, lapis lazuli, and malachite, which were mixed with binders and applied to a layer of plaster on the walls.

The painters worked in teams, using a grid system to maintain proportions. The quality of the artwork varied between tombs, depending on the time available before burial.

Some tombs, like that of Seti I, contain highly detailed and colourful scenes, while others, such as the tomb of Ramesses V and VI, reused older designs and motifs to save time.

Certain doorways featured protective curses to deter thieves, warning of divine punishment.

The most famous discoveries

No discovery in the Valley of the Kings has attracted as much global attention as the unearthing of Tutankhamun's tomb in 1922.

British archaeologist Howard Carter located the sealed entrance after years of searching, and the tomb's contents had survived nearly intact.

Inside were more than 5,000 artefacts, including a solid gold coffin, a death mask, ceremonial chariots, jewellery, and preserved food offerings.

The tomb offered the only example of a nearly untouched royal burial from the Valley of the Kings.

Designated KV62, it had remained hidden beneath debris from later tomb construction.

Other undisturbed royal burials have been discovered elsewhere in Egypt, such as those at Tanis.

Other remarkable tombs include that of Seti I, whose burial chamber displays some of the most elaborate artwork ever found in Egypt, and the vast tomb of Ramesses VI, which contains some of the best-preserved examples of astronomical ceilings.

The Valley also held non-royal burials, such as the tombs of several sons of Ramesses II.

KV5, initially dismissed as unimportant, was later revealed to be the largest tomb in the valley, with over 120 corridors and chambers, though the total number is still under investigation.

Each tomb, regardless of its condition, provided unique evidence about Egyptian religious beliefs, burial practices, and artistic development.

In recent years, CT scans and DNA analysis of royal mummies, including that of Tutankhamun, have offered new insights into ancient health and lineage.

Who excavated the tombs?

European interest in the Valley of the Kings began in the late 18th century. Early travellers such as Richard Pococke and James Bruce documented the valley and described some of the tombs.

By the early 19th century, antiquities collectors like Giovanni Belzoni and Jean-François Champollion entered several tombs and recorded hieroglyphs and removed artefacts.

Their work, though often careless by modern standards, led to significant discoveries.

The American lawyer Theodore Davis conducted extensive excavations and concluded, mistakenly, that the valley had been exhausted.

In the 20th century, systematic excavation began under the Egyptian Antiquities Service and foreign archaeological teams.

Howard Carter's methodical approach to Tutankhamun's tomb set a new standard for documentation and conservation.

Since then, scholars from Egypt, Europe, and North America have worked in the valley, using advanced methods such as ground-penetrating radar, 3D mapping, and digital photography.

Egyptian archaeologist Zahi Hawass, particularly active in the 1990s and early 2000s, has led numerous excavations and conservation projects.

The Supreme Council of Antiquities oversees all excavation and conservation projects today, while the Supreme Council of Antiquities ensures that these discoveries are preserved for public and scholarly study.

The Valley of the Kings today

Now protected as part of the UNESCO World Heritage site of Ancient Thebes, the Valley of the Kings is a major destination for tourists and scholars.

Several tombs are open to the public, with the tombs of Ramesses IX, Merenptah, and Tutankhamun open to visitors.

To reduce the damage from humidity and foot traffic, only a few tombs remain open at a time, and replicas of the most delicate tombs, like that of Seti I, have been constructed for educational purposes.

Annual visitor numbers can reach into the hundreds of thousands, which necessitate strict preservation measures.

Conservation efforts focus on stabilising tomb walls, repairing damage caused by early explorers, and protecting murals from moisture and salt crystallisation.

The Egyptian government has installed pathways, lighting, and ventilation systems to manage visitor numbers.

Laser scanning and photogrammetry are now used to create detailed digital records of tomb interiors.

Research continues in lesser-known areas of the valley, where teams still hope to find tombs that have escaped looting and erosion.

KV64, which was discovered in 2011, contains the burial of the priestess Nehemes-Bastet and is still under study.

In constrat, KV65 (a provisional designation) has not yet been formally confirmed as a tomb.

The valley is one of the most important archaeological sites in the world, and gives a rare look into Egypt's royal past.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.