How the Crusaders captured Jerusalem 1099 and the horror that unfolded afterwards

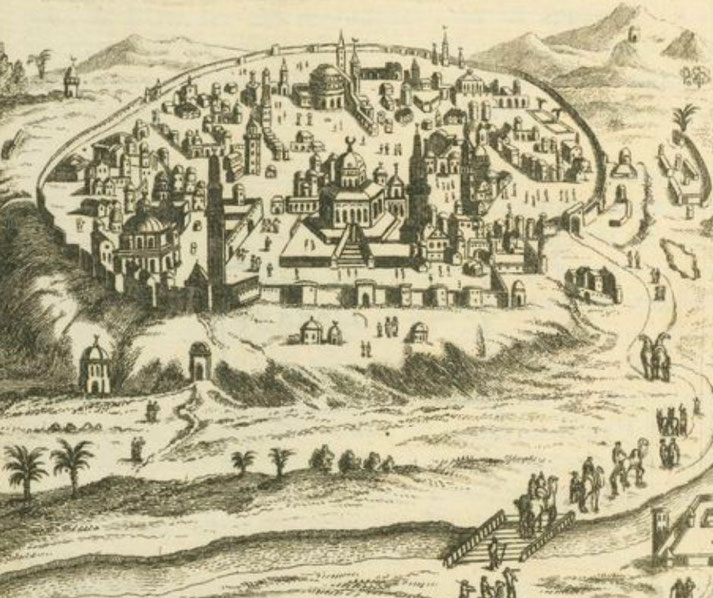

In July 1099, thousands of worn-out Crusaders reached the walls of Jerusalem after years of hard travel and difficult battles.

The city had long considered sacred to Christians, Muslims, and Jews, and had now become the central goal of the First Crusade.

What followed its capture would shock even medieval chroniclers.

What were Europeans doing in the Middle East in 1099?

Pope Urban II had launched the First Crusade in 1095 during the Council of Clermont, where he urged Christian knights to reclaim Jerusalem and protect pilgrims from alleged abuses under Muslim control.

He promised spiritual rewards, including full remission of sins, to those who answered the call.

His speech struck a chord across feudal Europe, where religious devotion and feuding nobles stoked internal strife that a restless warrior class seized to drive the campaign.

During the late 11th century, Western Europe experienced frequent local wars and few job opportunities, and strong religious feeling encouraged many knights and lords to look outward.

Urban’s call offered a solution to internal conflict by directing military aggression toward a cause deemed holy.

For some Crusaders, the campaign promised eternal salvation. For others, it provided a chance to escape debt, win land, or gain prestige.

Entire families sold their property to fund the journey.

Crusader armies began assembling in 1096. Some groups, such as the People’s Crusade led by Peter the Hermit, lacked discipline and faced disaster in Byzantine lands.

More organised forces followed, made up of contingents from France, Flanders, Norman Italy, and the Holy Roman Empire.

These armies crossed into Anatolia and pledged only superficial loyalty to the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos, though tensions soon developed over supplies, tactics, and the control of captured cities.

After the fall of Antioch, disputes arose over whether the Crusaders would honour their oaths to return conquered territory to the emperor.

However, victories at Dorylaeum in July 1097 and the long siege of Antioch in 1098 strengthened Crusader confidence, although disease and starvation claimed thousands.

By the time the surviving forces reached the outskirts of Jerusalem in early June 1099, they had marched for nearly three years through hostile terrain.

Estimates suggest that fewer than 14,000 Crusaders remained, including approximately 1,500 knights.

The city, which the Fatimid Caliphate had recaptured from the Seljuk Turks in 1098, now faced the full force of their attack.

The 1099 siege of Jerusalem

The siege began on 7 June 1099, as Crusader forces surrounded Jerusalem and prepared for a direct assault.

The defenders were commanded by Iftikhar ad-Dawla, who was the governor for the Fatimids and who had already taken defensive measures.

They poisoned wells, fortified gates, and drove livestock away to keep the attackers short of food and water.

The Crusaders, who had been weakened by the desert crossing, suffered from thirst and disease.

Hunger further weakened them as they built siege equipment in unfamiliar terrain.

Under the leadership of commanders such as Godfrey of Bouillon, Raymond of Toulouse, and Robert of Normandy, Crusader forces began building siege towers and battering rams.

Timber was difficult to obtain, since the surrounding landscape lacked forests, so they dismantled ships and buildings to salvage the needed wood.

A group of Genoese engineers, who had arrived at Jaffa, provided critical assistance in constructing the siege equipment.

Morale rose and fell as delays and heat wore down both soldiers and animals.

Then, on 13 July, the Crusaders launched a joint attack. Godfrey’s troops attacked from the north, where the wall was less fortified, while Raymond’s men targeted the southern gates.

Muslim defenders hurled stones, fired arrows, and poured boiling oil from the ramparts, which caused many casualties.

Regardless, two days of constant fighting wore down both sides and, on the night of 14 July, the Crusaders moved one of the siege towers to a new position opposite the northeast corner of the wall, which took the defenders by surprise.

On 15 July, Godfrey’s men pushed the tower forward and created a gap. He and his men crossed over a drawbridge onto the ramparts, forcing defenders to fall back in confusion.

As Crusader troops poured into the city, defenders either fled or attempted to regroup in fortified areas.

Jerusalem fell after more than four centuries under Muslim control. For many Crusaders, the moment fulfilled what they saw as a holy mission.

Some dropped to their knees and prayed at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, convinced that their sins had been forgiven by their role in the city's capture.

The massacre that followed the city's capture

Once Crusaders secured entry into Jerusalem, Christian chroniclers of the time described scenes of chaos and terror.

According to Raymond of Aguilers, Crusaders slaughtered every enemy they encountered, while Fulcher of Chartres wrote in metaphorical terms of blood flowing ankle-deep through the streets.

The anonymous author of the Gesta Francorum described the carnage in similar language.

Entire neighbourhoods turned into killing grounds, with no distinction made between soldiers, civilians, or clergy.

Muslims who sought sanctuary in the Al-Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock were surrounded and killed.

Those who hid in homes or attempted to flee the city faced the same fate. Amid the killings, Crusaders burned buildings and ransacked neighbourhoods, leaving widespread ruin.

Crusaders killed thousands, sometimes out of religious hatred and sometimes to secure spoils of war.

The scale of the massacre shocked observers and remains one of the darkest chapters of the Crusades.

Modern estimates vary, with some suggesting between 3,000 and 10,000 people were killed over the course of two days.

The Jewish population of Jerusalem faced similar horrors. Many had gathered in their synagogue for protection but, as contemporary sources claim, Crusaders set fire to the building, killing those trapped inside.

Chroniclers described the synagogue’s destruction in detail, viewing it as part of a divine cleansing.

No mercy was shown to those who practiced a different faith, and even those who offered ransoms or surrender found few protectors.

Muslim sources, including Ibn al-Qalanisi and later Ibn al-Athir, confirmed the scale of the killings.

They wrote of entire communities being wiped out and sacred places defiled. Ibn al-Athir, wrote in the early 13th century, and he described the massacre as a disaster without precedent.

The memory of these events helped fuel later calls for jihad as the massacre, which was widely celebrated in Western Europe, became a source of enduring resentment across the Islamic world.

After the slaughter, Crusaders held religious processions to give thanks. Survivors gathered at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre to pray.

Many believed they had achieved salvation through violence. The city, once diverse in its population, now became a Christian stronghold governed by foreign knights.

Justifications for the violence often drew upon biblical accounts of holy war, such as those in the Book of Joshua, which some Crusader clergy cited to explain the events.

What did the Crusaders do with Jerusalem?

Following the capture, Crusader leaders faced the problem of ruling it. Godfrey of Bouillon, who one of the most respected commanders, refused to be crowned king, claiming that he would not wear a crown of gold in the city where Christ had worn a crown of thorns.

Instead, he accepted the title "Advocate of the Holy Sepulchre" and he took on both a military and spiritual leadership role.

Crusader nobles divided the city’s religious and administrative sites. They expelled surviving non-Christians or placed them under strict control.

The Dome of the Rock was purified and used by Christian clergy. Later, the Al-Aqsa Mosque was given to the Knights Templar, who used it as their headquarters.

Latin clergy replaced the local Greek Orthodox priests, and Arnulf of Chocques was installed as the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem shortly after the city’s capture.

Pope Paschal II and European clergy praised the Crusaders' success and called for pilgrims to visit the city.

Also, Jerusalem was declared the capital of a new Crusader state: the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

Crusaders established vassal territories throughout the Levant, including Antioch, Tripoli, and Edessa.

These regions were held by Western nobles who ruled over local populations with military force, while they built fortresses and castles to protect the routes between ports and holy sites.

In 1100, following Godfrey's death, his brother Baldwin of Boulogne accepted the crown and became the first King of Jerusalem.

Over the following decades, the Kingdom developed administrative institutions and legal codes, including the Assizes of Jerusalem, to help rule over the Crusader elite.

Finally, Christian pilgrims began arriving from Europe, though security remained a concern, as many routes passed through hostile territory, and Muslim powers in the region never accepted the loss of Jerusalem.

In later decades, Fatimid and Seljuk rulers such as Zengi and, later, Saladin would campaign against Crusader strongholds.

In fact, Saladin ultimately recaptured Jerusalem in 1187.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.