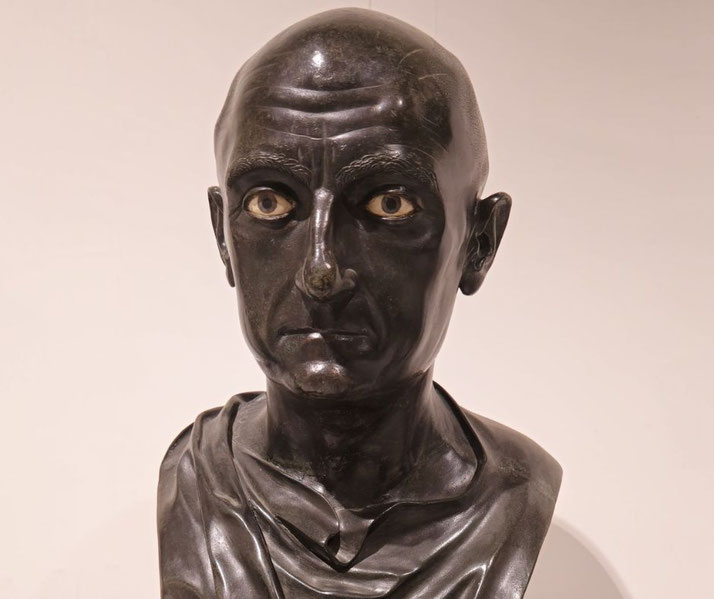

Scipio Africanus: The Roman military genius who finally managed to defeat Hannibal

During the Second Punic War, when Rome faced a determined enemy whose invasion had caused years of fear and devastation, Publius Cornelius Scipio, later granted the title Africanus, significantly transformed Rome’s fortunes by winning in Spain and through diplomatic cunning in North Africa, which led to his final defeat of Hannibal at Zama in 202 BCE.

His rise from a young noble to the Republic’s most celebrated general helped to change the future of Roman warfare and foreign policy.

Growing up in one of Rome's most famous families

Born in 236 BCE into the patrician Cornelii Scipiones, Scipio entered the world as a member of one of Rome’s best known families for political and military service.

His father, also named Publius Cornelius Scipio, had held the consulship and commanded Roman forces at the start of the Second Punic War, while his uncle Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio Calvus served as a senior commander in the same conflict.

According to Livy, Scipio displayed early leadership after the severe Roman defeat at Cannae in 216 BCE, where Hannibal's forces destroyed a Roman army and killed tens of thousands.

At that time, Scipio reportedly intervened to stop young Roman nobles from deserting the Republic, and he took charge despite his youth, which prevented a loss of morale among Rome’s political class.

By necessity, his political advancement bypassed normal steps. Scipio had never held the praetorship or any significant office before receiving independent command.

However, the Republic’s serious situation required men of talent more than strict legal process, and the people, trusting in his family name and personal reputation, approved his elevation.

He had been granted imperium pro consule, a special step that bypassed traditional progression through the cursus honorum.

His entry into military life

Scipio began his career in arms under his father’s command and fought at the Battle of Ticinus in 218 BCE, during which Hannibal's cavalry inflicted a sharp defeat on the Roman advance.

During the engagement, Scipio reportedly saved his wounded father’s life when he charged into enemy ranks, an act that later Roman writers praised as evidence of his bravery and loyalty to his father.

However, the sudden death of both his father and uncle in 211 BCE during campaigns in Spain created an urgent need for new leadership.

At that point, no senior Roman commanders volunteered for the position, and the Senate hesitated to assign the dangerous role to anyone without experience.

Scipio, who was around 26 years old at the time, offered himself for command.

Unexpectedly, the Roman people voted in favour of his appointment, giving him imperium without holding the consulship or praetorship.

This decision, unusual in its time, showed both a desire for renewed confidence and a recognition that traditional hierarchies had failed to stop the Carthaginians.

Officially, his title was proconsul, though he had never held the requisite offices.

Upon arrival in Spain, Scipio had inherited a discouraged army and a weak position. He recognised that unless Carthaginian power in Iberia collapsed, Hannibal would continue to draw reinforcements and resources from the region.

Scipio's command in Spain

In 209 BCE, Scipio had struck first with a risky plan to seize New Carthage, the enemy’s main port and base in Iberia.

He marched his forces quickly across rough terrain and launched a surprise assault, which caught the garrison largely unprepared.

He used tidal patterns to send troops across the lagoon at low tide, which allowed them to scale the lightly defended sea wall.

As a result, the city fell in a single day, and Rome gained control of significant supplies, warships, hostages, and access to Spain’s rich silver mines.

For the Carthaginians, the loss of New Carthage proved to be a severe blow. Many Spanish tribes who had previously supported Carthage began to question its strength and reliability.

Scipio used this moment to form alliances, and he treated local leaders such as Edeco of the Edetani with respect and he offered better terms, which largely helped expand Rome’s influence without further costly fighting.

He also reportedly released some of the hostages, who were primarily women, as a diplomatic move to encourage goodwill among the tribes.

In the following year, he fought Hasdrubal Barca at the Battle of Baecula.

Hasdrubal managed to break away and later cross into northern Italy, and while the battle delayed his movements, it did not result in his destruction.

However, the delay allowed Roman consular armies to prepare for his arrival. In 207 BCE, Hasdrubal’s forces were destroyed at the Battle of the Metaurus, ending the last serious attempt to reinforce Hannibal from Spain.

Then in 206 BCE, Scipio faced a alliance led by Mago Barca and Hasdrubal Gisco near Ilipa.

Before the battle, he reversed the traditional Roman deployment, he placed his strongest troops on the wings and he launched a dawn assault after several days that had lulled the enemy into complacency.

His ability to control both timing and terrain allowed him to outmanoeuvre and defeat a large Carthaginian force.

Mago fled to Gades, where his final attempts to resist ended in failure.

Soon after the victory, Carthaginian resistance in Spain collapsed. By the end of that year, Rome controlled the Iberian Peninsula, and Scipio had secured Rome’s first true overseas territory.

From there, he began planning the next phase of the war.

How Scipio beat Hannibal

After returning to Rome, Scipio ran for consul in 205 BCE. He won the election easily and requested permission to carry the war into Africa.

The Senate, unsure of the risks, granted him Sicily instead, with authority to act beyond it only if he could raise troops independently.

He accepted the condition and began preparations from Syracuse.

During his time in Sicily, he trained a volunteer army to high standards and formed an important alliance with Masinissa, a Numidian prince who had turned against Carthage.

Masinissa had been involved in a dynastic struggle with Syphax, the Carthaginian-aligned king of the western Numidians, and his support gave Scipio access to some of the finest light cavalry in the Mediterranean.

With Numidian cavalry and Roman legions ready, Scipio sailed to Africa in 204 BCE and landed near Utica.

His quick raids and victories forced Carthage onto the defensive. Eventually, the Carthaginian Senate, desperate for protection, summoned Hannibal back from Italy.

By 202 BCE, both armies met near Zama. Scipio arranged his forces to counter Hannibal’s elephants, by spacing his lines so that the beasts could pass through.

Also, he instructed his velites to attack them with javelins and sling stones, which caused confusion and panic in the Carthaginian front.

As the elephants fled or fell, the Roman cavalry, under Laelius and Masinissa, routed the Carthaginian horsemen.

Then, as the Roman infantry pressed the Carthaginian centre, the cavalry returned and struck from behind.

The encirclement finished the Carthaginian force. Hannibal’s army, which, according to Polybius, included around 36,000 men and approximately 80 elephants, broke apart, and he barely escaped the field.

Carthage, now unable to continue the war, asked for peace.

As part of the treaty, Carthage surrendered all overseas holdings, paid a large indemnity, and agreed not to wage war without Rome’s permission.

Scipio’s victory ended the Second Punic War and helped to secure Rome’s control in the western Mediterranean.

According to later accounts, Hannibal and Scipio met again during the former’s exile, where they discussed the merits of past generals.

Hannibal is said to have placed Scipio just after Alexander the Great in military greatness.

Scipio's career after the Second Punic War

Following his return, Scipio had received a triumph and had been granted the name Africanus.

His popularity soared, which gave him senior influence over Roman politics and possibly a role as princeps senatus.

For a time, he dominated Roman political life, guiding foreign policy and supporting allies.

However, his influence caused resentment, especially among conservatives such as Cato the Elder.

Over time, his opponents accused him and his brother Lucius of financial misconduct during their campaigns in the East.

Scipio, who was never convicted, refused to defend himself in court. According to tradition, he withdrew from public life and left Rome entirely.

Some critics viewed his luxurious habits and admiration of Greek culture as un-Roman, which further alienated him from the traditionalist faction in the Senate.

According to tradition, he died in 183 BCE at Liternum. He allegedly asked not to be buried in Rome, and his tomb bore the inscription: Ingrata patria, ne ossa quidem habebis: “Ungrateful fatherland, you shall not even have my bones.”

Yet, in military history, his name endured. Scipio Africanus combined tactical skill with political ability, and he succeeded where others had failed by defeating Hannibal in open battle.

His campaigns set the foundation for Roman imperial expansion and left a model of Roman generalship for generations to come.

Some later commanders such as Lucullus, Pompey, and Caesar would emulate elements of his strategic thinking and diplomatic methods, which ensured that his influence continued across the centuries.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.