Scipio Aemilianus: The Roman who finally destroyed Carthage

Scipio Aemilianus, who commanded the final destruction of Carthage in 146 BC, belonged to two of the most powerful noble houses in Republican Rome.

His victories in Africa and Spain, along with his influence in the Senate, allowed him to influence military conduct and political conservatism, which significantly affected elite cultural life during the second century BC.

As a result of his actions, he became one of the most celebrated and controversial figures of his time.

Living as part of the most powerful Roman family

Born in either 185 or 184 BC to Lucius Aemilius Paullus Macedonicus, Scipio Aemilianus came from a consular line that already held high standing within the Roman elite.

His father, who achieved fame by defeating King Perseus of Macedon at the Battle of Pydna in 168 BC, was an example of the kind of commander the Republic valued as it expanded across the Mediterranean.

As a result of his adoption in the same year by Publius Cornelius Scipio, the son of Scipio Africanus, he inherited the name and, to a large degree, the military expectations associated with the Scipio family name.

By uniting the status of two prominent families, his adoption elevated his political standing well above his peers.

He regularly moved in circles that included important senators, scholars, and military leaders, and he grew up surrounded by both the civic duties and cultural expectations that came with Roman nobility.

Importantly, his education under Greek tutors, particularly Polybius, gave him solid knowledge of philosophy and ethics and a reasonably good understanding of history.

As he grew older, those connections eventually helped him build a network of supporters who documented his life and defended his policies.

He also formed a close relationship with the same Polybius, who later accompanied him during the siege of Carthage and worked as a military advisor.

Eventually, his performance in early public roles revealed a combination of personal charm and discipline in administration.

Although Roman law required that consuls be over 42 years of age, Scipio's popularity and the crisis in Africa led the popular assembly to pass a special exemption.

Therefore, in 147 BC, he was elected consul at the age of 38 and granted supreme command for the campaign in the Third Punic War.

The Third Punic War and the siege of Carthage

Tensions leading to the Third Punic War arose largely from fear within the Roman Senate rather than any act of direct Carthaginian aggression.

After the Second Punic War, Carthage remained militarily weak but it traded actively.

Because Carthage had regained economic power, Roman senators such as Cato the Elder insisted that the city posed a potential future threat and must be eliminated.

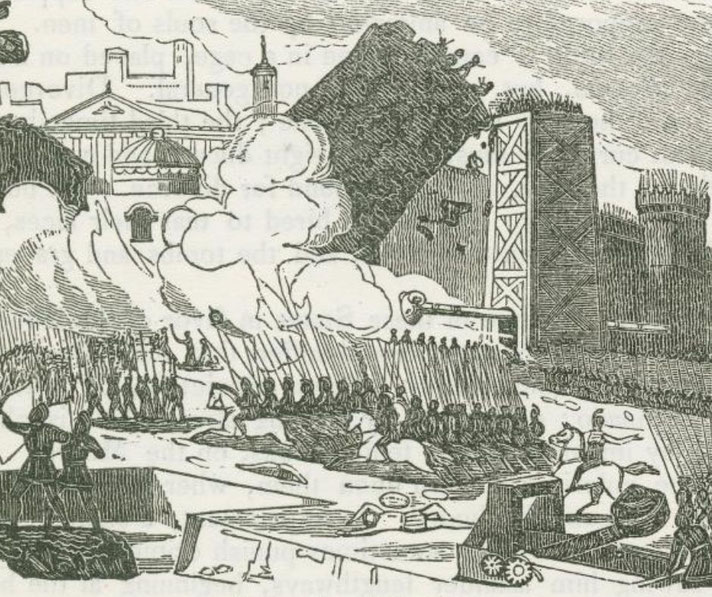

By the time Scipio landed in Africa, Roman forces had so far failed to breach the city walls after two years of siege.

Immediately upon assuming command, he reorganised the army, sent away non-essential personnel and punished any reported wrongdoing among his troops.

As discipline returned, morale largely returned as well. He used a strategy of containing the city and wearing it down, and he relied on engineering work and persistence rather than risky direct attacks.

To isolate the city, he ordered a siege wall to be built around the entire perimeter, which largely cut it off.

At the same time, Roman forces constructed a large causeway across the harbour mouth, which prevented Carthaginian ships from escaping.

In response, Carthage attempted to counter with a fleet hastily built in full view of the Romans.

However, Roman readiness and control of the sea largely caused that effort to fail.

Eventually, the final assault came in 146 BC after months of blockade. Roman troops entered the city and fought in brutal conditions as they advanced street by street, and fires raged while defenders, who often fought from rooftops and alleyways, resisted.

Over several days, thousands perished. Roman engineers levelled buildings, and soldiers killed anyone who resisted.

Civilians who survived were sold into slavery. Ancient sources reportedly claim that as many as 50,000 were enslaved and the rest killed.

According to Polybius, who personally witnessed the destruction, Scipio reflected on the fall of great cities as he watched Carthage burn.

He quoted verses from Homer, although his orders left no doubt that destruction had been his aim.

The city was destroyed, its land cursed, and its people scattered. Some later sources suggested that the Romans sowed salt into the soil.

However, no ancient author recorded such an act, and most modern scholars consider the claim a later invention from the nineteenth century.

Shortly after he had returned to Rome, he received the title “Africanus the Younger,” honouring the memory of Scipio Africanus and confirming Rome’s total control of North Africa.

The Senate soon established the province of Africa Proconsularis, which made Roman administration official in the region.

The Numantine War

By 134 BC, a new crisis had developed in Hispania, where the fortified city of Numantia had resisted Roman conquest for years.

The Senate was frustrated by repeated failures and again turned to Scipio.

Because of his record in Africa, they effectively ignored legal limits and awarded him a second consulship.

Upon arrival, Scipio found that the Roman army had been suffering severely from low morale and disorder.

First, he restored discipline once more by banning luxury items, removed traders from the camp, and kept the men on constant drill.

As a result, the soldiers gradually regained physical strength and a sense of purpose.

Rather than risk an assault on strong walls, Scipio constructed a ring of trenches, forts, and towers to cut off Numantia completely.

Eventually, as the siege dragged on, food shortages hit the city hard. The defenders were reduced to eating hides and grass, but refused to surrender.

Still, no reinforcements arrived. By the end of the siege, the survivors either starved or surrendered under harsh terms.

According to several accounts, many Numantines reportedly took their own lives rather than face slavery.

Scipio ordered the city destroyed and its people enslaved, and he repeated the strategy that had worked so effectively at Carthage.

Although the final phase of the Celtiberian Wars did not have the same stature as his African campaign, it demonstrated his commitment to endurance and siege warfare, enforced through strict command.

Once again, he achieved success where others had failed.

Scipio’s political reforms

Scipio’s political beliefs largely matched the traditional values of the Roman Senate.

He opposed any challenge to its authority, particularly reforms proposed by the Gracchi.

Although Tiberius Gracchus had married Scipio’s cousin, personal connections did not prevent public opposition.

Scipio believed that redistributing land and reducing senatorial power would likely weaken Rome’s internal stability.

After the murder of Tiberius Gracchus in 133 BC, Scipio openly supported the Senate’s decision, viewing the suppression of reform as a necessary defence of Roman order.

He returned to Rome shortly afterwards and was reported to have quoted a line from Homer, which suggested that justice had overtaken the unjust, a remark that caused some public outrage.

When later accused of misusing funds from the Spanish campaign, he refused to defend himself publicly in court.

Instead, he dismissed the charges and left the forum to offer thanks to the gods, an act that infuriated his critics.

Although offered the office of censor, Scipio declined it. Nevertheless, he continued to press for a return to traditional moral standards.

He criticised the growing taste for luxury, condemned laziness among the elite, and supported old religious rites.

His speeches and policies aimed primarily to restore what he believed had made Rome great.

Because of these efforts, his supporters praised him as a guardian of traditional virtue and his opponents criticised his rigidity.

In 129 BC, Scipio died suddenly while at his country estate. Some suspected poisoning, perhaps linked to political enemies, but no official investigation found proof.

Later writers, including Cicero, suggested political murder, though these accounts remain unproven.

His body was reportedly buried in private, and the absence of a public funeral shocked many Romans.

His death ended a career shaped by military achievement and political conservatism.

How Scipio changed Rome’s culture

Although remembered as a soldier and politician, Scipio Aemilianus influenced Roman identity in another way.

He supported Greek education and literature and encouraged a taste for Greek art among the Roman elite.

Because of his support, men like Polybius and Panaetius reached audiences in senatorial circles.

Their writings helped explain Roman expansion partly using philosophy and history.

At his home, Scipio regularly hosted discussions between generals, poets, and philosophers.

Greek sculptures, manuscripts, and artwork, which had been taken from Corinth and Carthage, decorated his residence.

He preferred works by Homer, Euripides, and Plato and helped save important libraries and collections during his campaigns.

When Roman aristocrats copied Greek tastes, it increasingly became a sign of learning and refinement.

As a result, Roman culture changed. Military achievement and traditional Roman virtues now blended with Greek intellect and aesthetics.

Eventually, the Scipionic Circle came to respresent a wider shift among Rome’s upper class.

Greek authors influenced Roman legal writing and rhetorical training, which helped inform artistic taste.

Scipio’s personal example encouraged other nobles to adopt similar interests, which further reinforced the idea that Greek learning and military conquest could go together.

By the time of his death, Scipio Aemilianus had significantly changed Rome's military methods, strengthened senatorial power, and set the tone for noble culture.

His conquests silenced two of Rome’s greatest enemies, while his ideals helped define what it meant to lead the Republic in an age of expanding power.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.