What was the Roman festival of Saturnalia and how is it linked to Christmas?

Romans typically welcomed Saturnalia each December with noisy street celebrations and public feasts that produced ritual disorder, which overturned the usual social structure.

Originally tied to agricultural rites in honour of Saturn, the festival gradually expanded over time into a prolonged civic holiday that occupied an important place in the Roman calendar.

Several of its customs, including gift-giving and winter gatherings, likely influenced the Christian development of Christmas.

The ancient history of Saturnalia

Romans traced the origin of Saturnalia to the early Republican period, although its religious elements likely developed from older Latin agricultural traditions that predated the city’s foundation.

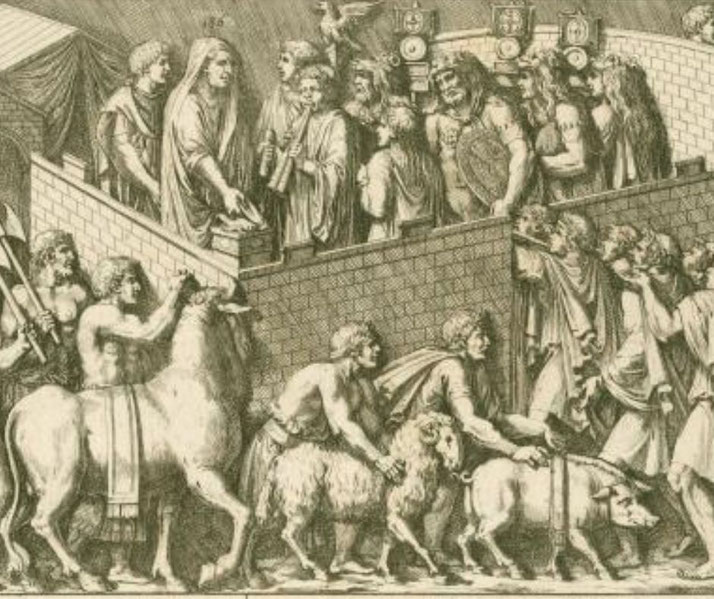

On 17 December, priests typically gathered at the Temple of Saturn in the Roman Forum to perform animal sacrifices and lead the public in a shared meal, which indicated the end of the autumn sowing season and the temporary closure of the year’s agricultural duties.

The date of the celebration generally remained fixed in the Julian calendar, but the length of the holiday lengthened over time, which suggested that it had become more popular.

By the late Republic, the original one-day celebration had generally lengthened into a multi-day festival, and under the Empire, it sometimes lasted from 17 to 23 December.

Magistrates often ceased their legal duties, courts often closed, and formal sessions of the Senate were often suspended.

Some writers such as Varro and Macrobius Ambrosius Theodosius described the festival as a moment of collective release, during which ordinary obligations gave way to prolonged feasting and relaxed social habits that encouraged ritual indulgence.

Macrobius Ambrosius Theodosius was a 5th-century, while Roman author Lucian of Samosata wrote in Greek and composed a satirical dialogue involving Cronus that parodied festive customs resembling Saturnalia.

As Saturnalia grew in scale, it tended to absorb nearby celebrations. It shared the December calendar with the Opalia, a festival honouring Ops, the goddess of abundance and Saturn’s consort.

Because both deities were associated with the fertility of the earth, their celebrations formed a seasonal pair.

Brumalia was a late imperial festival associated with Bacchus and other deities, and the festival’s proximity to it likely contributed additional festive energy to the season.

Over time, these connections gradually helped to strengthen Saturnalia’s identity as a festival that emphasised seasonal abundance and ritual renewal.

What did the Romans do during Saturnalia?

During Saturnalia, Romans often suspended the social order and encouraged behaviours that normally remained restricted to private spaces or theatrical performances.

In households across the city, the most dramatic custom involved the reversal of roles between masters and slaves.

Slaves often received the right to speak openly, eat with their owners, and wear garments usually reserved for free men, including the conical pileus cap that symbolised liberty.

In some cases, they were served by their masters and permitted to mock them without consequence.

Wealthy hosts often allowed their slaves to issue playful commands during feasts, and in some households, appointed one servant as the "King of the Saturnalia," or Saturnalicius princeps, who directed the household in absurd games and comic speeches.

Public celebrations were equally unrestrained. Gambling, usually forbidden, was temporarily permitted in many public spaces.

People of all classes rolled dice, placed bets, and played board games in full view of others.

Crowds filled the streets wearing colourful tunics, and men left off the plain toga in favour of brighter clothing.

As music and laughter spread through the city, Romans shouted the seasonal greeting "Io Saturnalia!" to friends and strangers alike.

Musicians, acrobats, and entertainers performed in marketplaces and courtyards, where they often used improvised acts or comic routines.

During the reign of Emperor Domitian, the festival received more official attention in some instances and formal structure, as the emperor tried to align himself with popular traditions and expand public enjoyment of the holiday.

Gift-giving was an essential part of the festival, with wax candles, called cerei, being common offerings, which were meant to symbolise light returning after the solstice.

Clay or wooden figurines, called sigillaria, were sold in markets set up specifically for the occasion.

On the final day of Saturnalia, many Romans visited these stalls to purchase tokens for friends, family, and dependents.

Sometimes the gifts were humorous, which included joke items or parody objects.

At other times, they carried gifts that had sentimental or practical value. Because gifts allowed people to express affection or loyalty without formality, their exchange reinforced personal ties across households and classes.

What did the Romans think of the celebrations?

Some Roman authors wrote about Saturnalia with approval and amusement, and some authors voiced measured concern about aspects of the festival.

Catullus called it “the best of days,” while Martial published dozens of short poems linked to the festival, especially focused on the giving of presents.

He joked about cheap wine, reused clothes, and peculiar knick-knacks. His verses made light of the season’s excess but acknowledged its importance in preserving goodwill.

Others viewed the holiday from a distance. Pliny the Younger described how he removed himself from the noise of the household in order to read and write because he did not condemn the festivities, but he preferred to avoid them.

Seneca wrote as a Stoic and remarked that Rome sounded like one continuous tavern during the festival, a comment that implied both irritation and resignation.

For some members of the upper class, Saturnalia allowed too much freedom, and its chaotic energy threatened to spill over its limits.

Some criticism existed, yet few Roman leaders seriously challenged the holiday because its rituals provided a controlled outlet for frustration.

For one week, people who wished could mock authority, relax their duties, and indulge in disorder.

When the holiday ended, citizens returned to their proper places, and the state resumed its usual routines.

Since Saturnalia gave structure to disobedience, it helped keep Roman life stable.

Did Saturnalia become Christmas?

Despite popular claims, Saturnalia did not become Christmas directly, but its customs likely shaped how early Christians constructed their own midwinter holiday.

By the fourth century, Church leaders began to observe the birth of Christ on 25 December because that date had lain only a few days after the close of Saturnalia and had coincided with the Roman celebration of the Dies Natalis Solis Invicti, or “Birthday of the Unconquered Sun”.

Emperor Aurelian had officially established the festival in 274 CE and had associated it with sun worship and the return of divine light.

Since that solstice celebration had already emphasised the return of light and the rebirth of cosmic power, the Church could reinterpret its message in terms of Christ.

Because Saturnalia had remained so popular, some of its practices had likely persisted among Christian converts, according to several historians who saw continuities in customs such as gift-giving and feasting, and in the use of decorations, and people had continued to exchange presents, hold family meals, and decorate homes with greenery and candles.

Over time, these customs gradually became linked to Christian values. Candles came to represent Christ as the light of the world; gift-giving was framed as charity; and the mood of merriment and generous public celebration endured, although its symbols and stories changed.

Pope Gregory I later told missionaries in Anglo-Saxon England to adapt familiar local rituals for Christian practice instead of abolishing them.

As Christianity had spread across the empire, it had largely absorbed local rituals without needing to erase them completely.

Saturnalia’s reversal of roles at times allowed slaves to command their masters and later reappeared in medieval festivals such as the Feast of Fools, where lower clergy mimicked their bishops.

The idea of merriment as a temporary release survived, as did the belief that light and laughter could overcome winter darkness.

Similar inversions occurred in Twelfth Night celebrations and the medieval Lord of Misrule.

When the early Church had sometimes allowed continuity of custom alongside a new religious meaning, it ensured that Saturnalia would continue to influence winter celebration.

The name of the god had gradually faded from memory, but the behaviours he had inspired had largely continued.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.